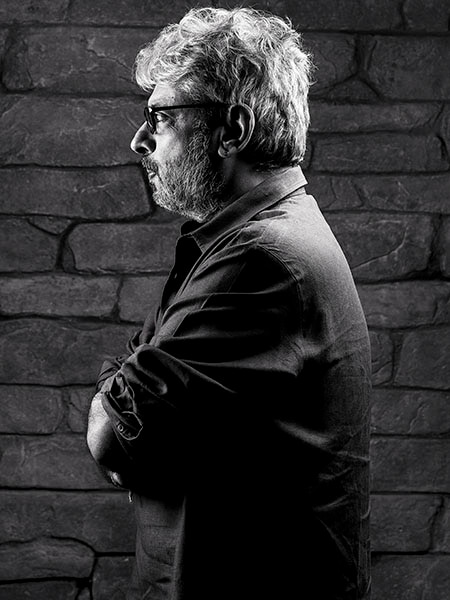

Black and white: How Sanjay Leela Bhansali straddles different worlds

Sanjay Leela Bhansali is a man of contradictions: He directs masterpieces, and produces potboilers. He is a task master who is loved by his team. He splurges on his movies, but remains aware of the despair that debts bring. He is a dreamer who is also a realist

Forbes India Celebrity 100 Rank No. 75

Image: Joshua Navalkar

They are expecting him any moment now and speak about him in soft, but respectful tones.

His film crew, aware of his obsessive attention to detail on the set, is ensuring everything measures up to his standards. Assistant directors and the camera team huddle to discuss deliverables for the next day’s shoot; painters and craftsmen apply final touch-ups; workmen hammer on wooden planks and metal sheets; and cleaners remove scrap from the floor.

The set conforms to the spectacular production values associated with his films. A crew member points out that only a select few are permitted on these fiercely-guarded premises. Photography is prohibited. Before we can respond, there is a stir and someone whispers: “He’s here.”

Sanjay Leela Bhansali has arrived.

After delivering two blockbusters in three years, Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela (2013) and Bajirao Mastani (2015), the 53-year-old filmmaker, producer and music director is in a very creative phase. The films he has directed have won critical acclaim, his cast and technicians have won bagfuls of awards, the songs he has composed have become chartbusters, and the films he has produced have sent the box office into a tizzy.

Bhansali carries a reputation of being a tantrum-throwing authoritarian, an ostentatious showman whose films are distant from reality, and a high-brow artiste who lives in a bubble.

But spend some time on his sets, speak to his team members, and you discover another personality, one diametrically opposite to the popular perception: A Bhansali who is patient, popular, self-effacing, and sensitive to diverse opinions.

Does he live in two different worlds? What makes him so complex?

We found out over the next couple of hours.

★ ★ ★

We are seated outside his film's set in Bandra’s Mehboob Studios, where parts of his debut film, Khamoshi: The Musical, were shot. Bhansali looks relaxed and pleased with the preparations for his next film, Padmavati.

Through his conversation with Forbes India, there is a reference to a theme, one that has influenced his films, creativity, values and ambition: Bhuleshwar, a South Mumbai neighbourhood where century-old temples and wholesale markets stand cheek by jowl. It is an unlikely place for an avant-garde artiste to thrive. But back in the 1970s, its bylanes housed talkies, including Alankar, Central, Shalimar, Imperial, Taj and Moti, where a young Bhansali developed his lifelong love affair with the movies. However, he also recalls being bitten by the film bug much before that. Navin, Bhansali’s father and producer of films such as Jahaji Lootera (1957), visited a film set one day, with his young son in tow. Sanjay was “fascinated” by the energy and action around a song being shot. “A cabaret,” he laughs, recollecting his father’s embarrassment at the discovery.

From that day on, he knew he belonged on the film set. But films also brought pain to the Bhansalis, when Navin’s movies failed at the box office.

Sanjay remembers walking with his grandmother from his home in Bhuleshwar to Colaba and back (a distance of 16 km) to recover Rs 10,000 that a producer owed his father, but returning empty-handed. Angry creditors turning up at their doorstep is another vivid memory. “This is my association with films. And that’s why I make those big films. Those ten thousand rupees have to come back to me with interest—I want those under any circumstances. Now you know my melodrama comes from there; the need to express that humiliation that you go through.”

His cinematic language is in large part a byproduct of this misfortune. For instance, he attributes his love for architecture, reflected in the production design of his films, to growing up in a small, “claustrophobic” home. “I used to repaint the walls, pushing them behind, making space bigger, redoing it, changing the pillar—my mind as a child was doing this all the time. With the misfortune of being deprived of aesthetics in the chawl I lived in—and my soul craving for it—I was always rearranging spaces.”

Sanjay Leela Bhansali (centre) with actors Ranveer Singh and Deepika Padukone

Image: Getty Images

He also credits his early exposure to music to his father, who introduced him to the best of Indian classical and Hindi film music. Records of Ustad Abdul Karim Khan, Roshan Ara Begum and Pandit Omkarnath Thakur stacked alongside the likes of Lata Mangeshkar, Madan Mohan, Naushad, and even Dada Kondke. He recalls how his father took him to watch Mughal-e-Azam 18 times, just to hear Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sing ‘Prem Jogan Ban Ke’ and ‘Shubh Din Aayo’.

Such influences also shaped his own compositions when he turned music director with Guzaarish, without any formal training. The music of Ram-Leela and Bajirao Mastani have been raved about for being influenced by India’s folk and classical music. Bhansali’s reinterpretation of the bandish ‘Albela Sajan’ (used in its original raga Ahir Bhairav version in Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam) in raga Bhoopali for Bajirao Mastani, is a bold experiment.

“Over the years, I learnt from the music directors I have worked with. So I didn’t just randomly and spontaneously jump in [saying] that I know music. I do not live without music. It is my biggest reason to create, to express: How would I shoot this song, how would I have arranged this song? All the workouts that people do in a gym, I do on the radio.”

Inevitably, Bhansali went where his destiny beckoned. After being expelled from the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune (over a disagreement related to his diploma project), Bhansali assisted documentary filmmaker Shukla Das for a while, before director and producer Vidhu Vinod Chopra invited him to assist on Parinda (1989) and 1942: A Love Story (1994). Bhansali remains grateful to Chopra for teaching him much more than filmmaking over the next seven years—especially to speak up.

In 1996, Bhansali released his first film, Khamoshi, which, he claims, was called the ‘Razia Sultan of the Decade’ by trade magazines; it was a classic that failed at the box office. But Bhansali bounced back with Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999) and Devdas (2002).

“When I celebrate love, when I celebrate Indian music, a lot of people call me melodramatic, a tamaasgir or nautanki [theatrical showman]. They feel my films are more ram-lila [dramatic folk story-telling] than cinema. My cinema is theatrical, yes, but that’s the art form that has fascinated me. It’s that celebration of the theatre and cinema that comes together, and then there is music and dance. My songs are very proud, artistic moments for me.”

His next film, Black (2005), with Amitabh Bachchan and Rani Mukherji, did well, but Saawariya (2007) was slammed as the ‘Twin Towers’ of the box office. However, it remains one of Bhansali’s favourites. He admits that as a director, it was not an easy failure to take. But as a producer, he insists he does not think too much of a film’s financial performance. “When I am making a film, I want what I want. I am never going to take this shot again. I am never going to shoot this scene again. I am never going to come to this place and see the way I am seeing it, again. I am never going to make this story or film again. So I have been very honest. If the film does well, it does well. My bank balance would be negligible or laughable. If not, I will learn from the experience.”

Bhansali is being unduly modest. After Saawariya, he admits he was the highest-paid director in the country. Even today, he is the highest-revenue-earning director in Forbes India’s latest Celebrity 100 list (rank 75).

“When I made Sawaariya and it did not do well, and they [critics] said go back to Devdas, I made Guzaarish immediately after that. They said this is harakiri, it makes no business sense. You have put Hrithik [Roshan] on the bed, and he’s not moving anything except his head. I knew it was a risk to make it after a film like Saawariya. But I said I want to make this at this point of time. I do not know what box office predictions, calculations and permutations are.”

★ ★ ★

But Bhansali does know. He is quick to point out corrections if I stray even by a crore in my box office facts. Yet, he is willing to compromise everything else in favour of his films. He breaks into self-deprecatory laughter as he remembers how actor Rekha dropped in to congratulate him for the success of Devdas, and was amused to discover that he lived in a one-bedroom, 450-sq-ft home, which he shared with his mother, Leela.

Social interaction is not his forte though, perhaps because of his childhood when he avoided his father’s creditors. “So going away from people is a part of what cinema brought to me: That you can’t face certain facts; you have to go away. So I won’t come out to a party today. I will not come into public today,” he says.

His inability to indulge in small talk could be another reason he is misunderstood. “A lot of people who have misconceptions about who I am, of being this arrogant, outspoken, foul-mouthed, abusive [person] is all coming from the image that they have created from the work that is a little inaccessible. Devdas, or Black, as films, are not very accessible, and you have started attributing that image to me.”

And just when you think he is getting contemplative, he asks with a throaty laughter: “So, in your eyes, have I now absolved myself of all the wrong images?”

It is this ability to see humour in serious situations, stay animated and connect with people, that has endeared Bhansali to his team.

Two-time National Award winning cinematographer Sudeep Chatterjee, who has worked with Bhansali on Guzaarish and Bajirao Mastani, wonders where the “myth” of the director being temperamental originates. “What he says to me in those fits of anger is actually very funny. Whatever he is doing or saying is for the benefit of the film. Here, you have a man who is breathing films 24x7. After a shoot he goes back, works on the music or script. He is up at 2 am or 3 am, fine-tuning a scene. He is on the set before everyone. A person like that is bound to be temperamental, but there is no negativity in that. And whoever gets a shouting will get a hug in the course of time. If you ask the unit people, everyone loves him.”

Bhansali admits he occasionally loses his calm, reprimanding the crew for any lapse in focus. “When I am watching all my films on my death bed, I don’t want to live with that mistake because of you. So I care for that image which is sacrosanct; that is what I pray to. We pray to images, we pray to some form in front of us. My God lives on my catwalk. I don’t have to go beyond that,” he says.

Chatterjee also describes him as being “ridiculously open to suggestions”, considering feedback from anyone if it is valid. In Bajirao Mastani, a twilight battle sequence was shot in daylight, he says, and credits Bhansali for encouraging such experiments.

While he is harsh on sloppiness, the director is sensitive to genuine concerns. Chatterjee narrates an incident where he requested a reshoot of an entire day’s work to improve a scene. Bhansali agreed. “Not just that, he completely had my back. He never told anyone else why we were reshooting. It just gives you a lot of confidence to have somebody like that backing you up,” Chatterjee says.

Bhansali chooses his team carefully and has an eye for talent. Many popular names such as Ismail Durbar, Shreya Ghoshal, Shail Hada, Nusrat Badr, Monty Sharma, Ranbir Kapoor and Sonam Kapoor made their debut with Bhansali. “When they come in, they come with another perspective. I want to see their perspective, I don’t want to stagnate by saying I know it all and it has to be done only my way. My biggest asset is that I haven’t stopped learning. I have not stopped receiving. And I am very self-critical,” Bhansali says.

Hrithik Roshan believes the director stretches his actors to extremes they have never explored before. “Working with Bhansali is something I will cherish the most. He is the only director who pushed me beyond my own boundaries. I didn’t know where my boundaries were. He made me discover them and then pushed me beyond them. And he does it with so much ease!”

The push is in the form of creating an emotional, spiritual and physical environment that puts actors in such an “inspired” state, that they would be able to “literally fly”, Roshan adds.

“What they think as freedom, is what I am tapping in them, without them realising it. I want them to feel they are doing it. If you do not have the freedom to ask me a question, then how are you going to talk to me or going to understand me?” says Bhansali.

And what if they do not deliver?

“I take you through the grind till I get what I want. But I won’t tell you how to do it. You have to interpret it yourself. That is why you are there. You evolve as an artiste, I evolve as an artiste. The audience also has to see it in their own way. That’s how it is,” he adds.

This ‘understanding’ is critical to Bhansali, another reason why he has frequently collaborated with the same actors, like Salman Khan, Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, Priyanka Chopra, Deepika Padukone and Ranveer Singh.

After Ram-Leela and Bajirao Mastani, Deepika and Ranveer will feature in Bhansali’s next production, Padmavati, a film that has been on his mind for almost nine years. After the Saawariya debacle, he rediscovered himself while directing his own interpretation of French composer Alberto Roussel’s 1923 opera titled Padmâvatî, inspired by the story of Rani Padmavati of Chittor. The opera had a successful run in France and Italy in 2008, and Bhansali believes the story now needs to be told on celluloid. The movie is slated for release next year, and promises to have all the quintessential ingredients of a Bhansali film.

Like Satyajit Ray and Charlie Chaplin, who composed the soundtrack of their own films, Bhansali had concerns about expression through music. “How do you translate that thought, which comes with a sound, to somebody else? It gets lost in translation or sometimes lost in ego. In today’s times, everyone thinks, ‘We know it all; what are you telling us? Why are you explaining it to us? We will give you the soundtrack. If you like, keep it, or else don’t keep it.’ The whole approach has changed,” says Bhansali, who watched RD Burman compose the songs of 1942... Another Bengali giant who left a deep impact on Bhansali is Ritwik Ghatak. He remembers watching Ghatak’s iconic Meghe Dhaka Tara in an auditorium and weeping. His other major influences include classic film makers such as V Shantaram, Raj Kapoor, Kamal Amrohi, K Asif, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy, Vijay Anand and Andrzej Wajda.

Strangely, as a producer, he has made choices that seem out of sync with his banner: Gabbar is Back, Mary Kom and Rowdy Rathore, to name a few. But that is his true love. “I go to Chandan Talkies, on the first day of Rowdy Rathore. I can’t hear a dialogue of the film. I can’t hear a single song. The minute a song would start the aisles would be filled with people throwing coins and dancing. And I said ‘this is catharsis’; the reaction of an audience that feels that this is the art that we want. I care a damn for your cerebral art and your Spanish, Korean and French cinema influence!” he says.

The film reminds him of the area he grew up in, watching masala films like Fakira, Chor Machaaye Shor, Pratigyaa, Rampur Ka Lakshman.

Asked if he would want to direct a movie like that, he says, “I am dying to. I want to make one film with abandon where I am not wondering about the aesthetics of a frame, and worrying about the one moment that will touch and choke the audience. Through Rowdy..., I felt that I did give back something that I learnt from and I enjoyed, but I want to make it myself —some mad film. Of course, [the critics] will attack me saying. ‘He’s forgotten filmmaking, He is over. He’s lost his art; he’s lost his aesthetics’.”

But that can wait for later.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali gets up and returns to his set. The director and his cinematographer discuss something. Finally, they grin, and Bhansali draws in a deep breath. He is ready to direct his next magnum opus.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)