Surviving 2020: How the young and restless dealt with the Covid-19 standstill

Chefs, sportspersons, musicians saw their year snatched away from them—with plans, practice, tours put on hold amid the coronavirus wreaking havoc—here's how they dealt with it

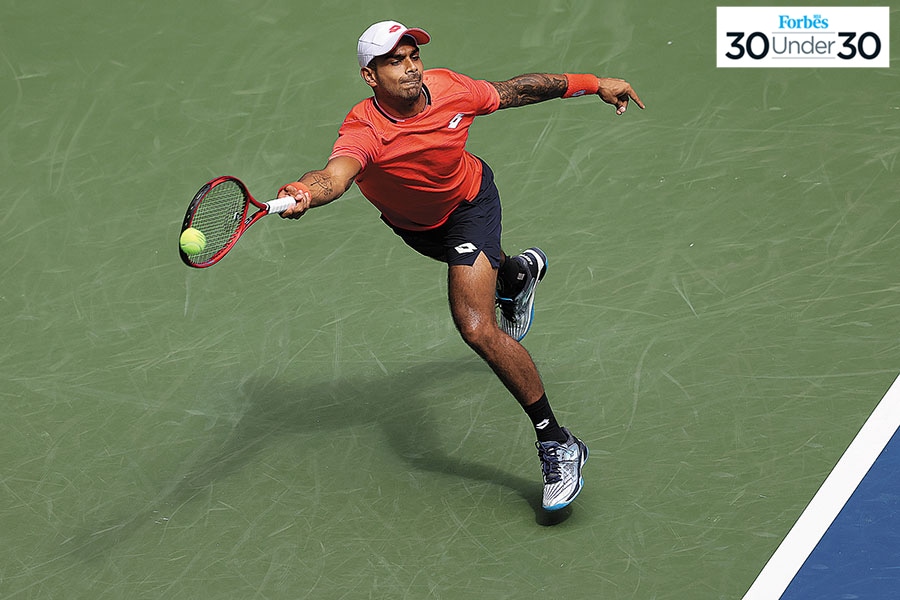

Sumit Nagal playing at the 2020 US Open. Nagal used the lockdown months to work on his serve, backhand and his left side. Al Bell/Getty Images/AFP

Chef Saransh Goila started 2020 on the high of a pop-up at London restaurant Carousel in February, and with grand plans of scaling up his brand Goila Butter Chicken (GBC) across India. Talks were on with partners in Pune and Bengaluru and two outlets were slated to open in Pune in March. Goila was also prepping for a digital show, Sadakchef, to be streamed between June and September. But days after he returned from his two-week culinary residency in the UK, the Covid-19 pandemic spread like wildfire and most countries, including India, went into complete lockdown.

“In no time, we were out of business for three months, till May. Not only did we have to stall plans of scaling up, our brand of non-vegetarian food suffered the most over rumours of the virus jumping from domesticated animals to humans and of travelling through cooked food,” says the 33-year-old. Food delivery as an essential service was allowed to stay open, but orders plummeted despite busting Covid myths on his popular social media handles and pushing pleas to salvage the livelihoods of his 40-odd staff members. “We tried everything, but nothing worked,” he adds.

The itch to build and create is synonymous with the young and—as the cliche goes—the restless. Youth, after all, is when we learn and unlearn, fall and rise. Until you face a seismic year like 2020 that upends the ways of the world. How did emergent stars deal with a Black Swan event like Covid-19, which brings their ascent to a screeching halt? With chaos, to begin with, and disappointment.

Rapper Divine was scheduled to go on a world tour, starting with the US. But instead he spent months at home composing music, which he had not been able to do before. Credit: Glitch

Rapper Divine aka Vivian Fernandes, 30, of Gully Boy fame was all set to embark on a world tour, beginning in the US, the birthplace of hip-hop, while tennis player Sumit Nagal (23) was building a CV that would qualify him for the Olympics, scheduled for July. Divine’s tour was cancelled as international borders closed, and Delhi boy Nagal, who headlined in end-2019 for taking a set off Roger Federer at the US Open, was told after landing in California for the Indian Wells Masters that the event had been called off.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)