The Tata-Mistry civil war and its ramifications for India Inc

At the core of the ongoing boardroom battle at the $103-billion Tata group, one of India's most important corporate institutions, is a serious deficit of trust. How it plays out will have ramifications not just for group companies but also for Corporate India

Ratan Tata (front row, left) and Cyrus Mistry (second row, left) have been involved in a public spat since the latter was unceremoniously removed as Tata Sons chairman on October 24

Image: Jasjeet Plaha / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

To better understand the unprecedented power struggle currently playing out at Bombay House, the headquarters of the storied Tata group, it would be worthwhile to get one’s hands on the epilogue, written by Ratan Naval Tata, to RM Lala’s book The Creation of Wealth: The Tatas from the 19th to the 21st Century.

Ratan Tata writes that after his predecessor and uncle JRD Tata informed him in 1991 that he would be the next chairman of the group, Tata, who turns 79 in December, had told JRD that he would always look to the latter as someone he could turn to. “And although I said that and I meant it, I did have some concerns that Jeh [as JRD was fondly known] would be in the office every day, and he would interfere and that he would forget that he was no longer the chairman, that he would be irritable and render somewhat impotent the moves that I was hoping to make.”

But Tata admits that his initial apprehension with respect to JRD’s interference was unfounded. “He acted as a senior statesman. He was available for counselling, he was available for advice, he was available for guidance. He was my best advisor,” Tata says of his predecessor.

Later in the epilogue, Tata explains the “moves that he was hoping to make,” which he eventually made, to restructure the diversified group to become more competitive, to provide better returns to shareholders, and to be more nimble-footed. “Broadly, the plan was to critically look at various companies through a group mechanism, which in fact did not exist.”

Tata, who was chairman for two decades till 2012, employed some “welding mechanisms”: The creation of the Group Executive Office comprising executive directors of Tata Sons responsible for overseeing the performance of various group businesses, while respecting their autonomy to take decisions; the creation of a unified brand with a common logo which would be used and displayed by all the companies; a set of operating requirements governing the use of this common brand; and a code of conduct to embody the group’s value system.

Tata is widely credited with solidifying the Tata group’s image as a symbol of India’s responsible capitalism, with businesses spread across the world, earning a collective turnover of over $103 billion. And to a large part, his decision to unify these diverse businesses under a single conglomerate structure, with commonality of purpose embodied through common personnel manning various group entities, can be said to have catalysed this success.

During his tenure in the corner office of Bombay House, Tata was the chairman of Tata Trusts, a clutch of philanthropic trusts that collectively own a majority 66 percent in Tata Sons, the chairman of Tata Sons, the flagship holding company of the group and the chairman of the various group operating companies in which Tata Sons was the main promoter shareholder.

THE GENESIS

It is little surprise then that when Ratan Tata’s successor was perceived to be tinkering with the conglomerate structure which he had painstakingly put in place over two decades, it created unpleasant ripples.

When Tata passed the baton to the 50-year-old Cyrus Pallonji Mistry—who was given the reins of the business house after impressing a selection committee with his vision for the group—in December 2012, he would have perhaps hoped that the younger son of Pallonji Mistry, whose family owns 18.4 percent in Tata Sons, would think of Ratan Tata as a senior statesman and advisor. Much like Tata thought of JRD while enjoying a free hand to shape the group’s destiny.

Indeed, the pleasant visuals of Tata and Mistry making public appearances together seemed to suggest that that was the case.

When asked what his advice to Mistry was, Tata had remarked that he had asked his successor to “be his own man”. Mistry, significantly, was the first Tata Sons chairman who was not chairman of either or both of the two principal Tata Trusts—Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and Sir Ratan Tata Trust which, together, hold the majority of the controlling stake in Tata Sons.

But as it now appears, being his own man meant different things to Tata and Mistry.

Mistry was taking decisions that were being perceived as being an attempt to dismantle the conglomerate structure of the group; and seemingly making Tata Sons and Tata Trusts less relevant. And that was unacceptable to the old guard.

On his part, various communications issued by Mistry suggest that he saw Tata, and the trusts that he continues to chair, as the kind of interference that Tata had hoped he wouldn’t face from JRD.

Mistry has defended his strategy of empowering group operating companies to a greater extent by saying that this would lead to more targeted, effective and quick decision-making, keeping in mind the realities in which different businesses operated as well as better corporate governance.

“Cyrus wanted Tata Sons to function as a kind of corporate centre and be a provider of support—mostly financial and strategic in nature—as and when needed by operating companies,” says a source close to Mistry. “His idea was to install people with domain expertise at the level of the group operating companies who would take decisions in the best interests of those entities.”

Sources in the Tata Sons board, however, read Mistry’s moves differently. “Ample indications were given to him that things were not as they should be. There were serious differences of views for some time on a variety of issues. In fact, there were differences on the outlook for the group as a whole—about keeping it cohesive,” a top Tata Sons source tells Forbes India.

He explains that in the structure which Ratan Tata put in place, Tata Sons was one binding shareholder, though its shareholding varies in group companies. Then there were the codes of governance, ethics, and a common management pool through the Tata Administrative Services. “There was a feeling that that was beginning to drift apart and the commonality was fading away.”

As an example of this apparent “fading away”, Tata Sons sources cite an instance in 2015 when the government came out with a defence contract for futuristic infantry combat vehicles. Tata group companies were found to be bidding with different external partners rather than together. This was despite the engineering expertise residing within the group which they feel could have been leveraged to bring a larger, and recurring, share of the Rs 60,000 crore contract to the conglomerate. “People were wondering why two Tata companies were competing rather than collaborating for the same contract,” the source says.

He adds: “I don’t know to what extent Cyrus accepted the fact that the trusts are the owners of Tata Sons. But they are the owners. They don’t behave like typical owners but surely they are very watchful [and ensure] that the activities of the group are not such that their own existence is in jeopardy. Remember, their activities are in philanthropy and not commercial [areas].”

Another sore point in the Tata-Mistry relationship has been the composition and role of Mistry’s core team—his Group Executive Council (GEC)—which was disbanded immediately after Mistry was suddenly replaced as Tata Sons chairman on October 24. Tata veterans and Tata Sons board members have had serious reservations against at least two GEC members who worked closely with Mistry — Nirmalya Kumar, who headed strategy, and Madhu Kannan, who was in charge of business development. While sources close to Mistry maintain that the former chairman was entitled to pick his own team and strongly refute that the GEC was any kind of alternate power centre, Tata Sons sources say there were some GEC members who were acting in contravention to Tata values and ethics.

“So much of the running of the group had been outsourced to two or three people in the GEC. They were intrusive in the affairs of group companies,” the Tata Sons official says.

Just as Tata Sons had issues with Kumar and Kannan, Mistry also seems to have had reservations about the role played by the managing trustee of Tata Trusts, R Venkataramanan. Among other things, Mistry has accused Venkat, as he is popularly known in the group, of pushing Tata Capital to extend a loan to C Sivasankaran that turned bad. A source close to Venkat, however, counters this by saying that the loan was extended to Sivasankaran’s Siva Group after following due process and securing adequate collateral.

It is this divergence of views that is at the core of the bruising—and very public—power struggle which has broken out at the House of Tata. It is a boardroom battle which also has far-reaching implications for Indian corporations at large. Contentious issues range from the level of information which should be shared with controlling shareholders to the role of independent directors (IDs).

GROWING TRUST DEFICIT

While the trust deficit between the two sides had been growing for the last couple of years, insiders say matters reached a tipping point earlier this year when it was felt that important business decisions were being taken without keeping Tata Sons and Tata Trusts in the loop.

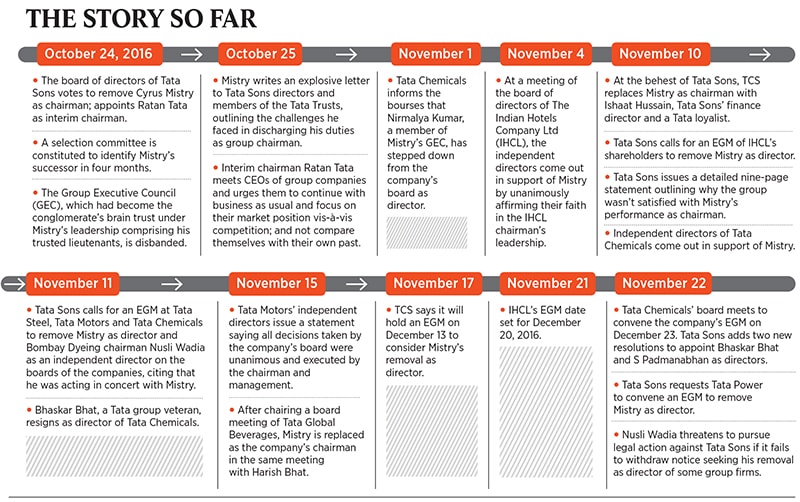

Consequently, in a swift and unexpected move, the board of Tata Sons voted to replace Mistry as its chairman on October 24. The resolution to vote out Mistry, who has been a Tata Sons director since 2006, wasn’t explicitly mentioned in the agenda of the meeting. Rather, it was discussed as part of the residual items that merit the board’s attention at the end of every meeting. Sources close to Ratan Tata say that Mistry was offered the option of resigning and making a graceful exit, but he refused. However, those close to Mistry say he was asked to resign only minutes before the board meeting and that the scion of the construction major Shapoorji Pallonji Group chose to opt for a board vote instead. Six members of the board, including Ajay Piramal, Venu Srinivasan, Amit Chandra and Nitin Nohria, voted in favour of his removal, while two—Ishaat Hussain and Farida Khambata—abstained.

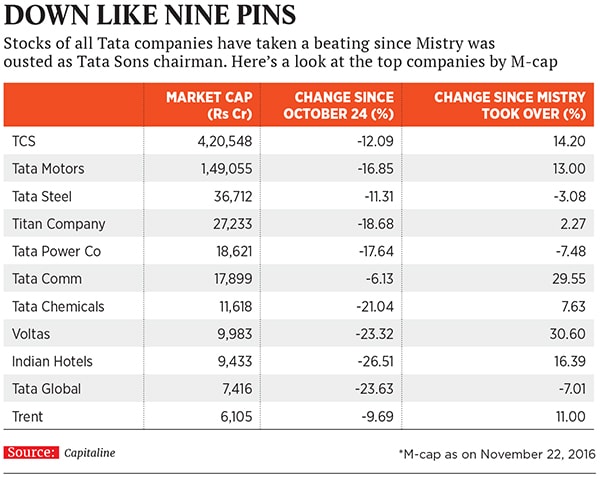

The developments that have unfolded since, especially at the level of the group operating companies, have led to the creation of two power centres within the conglomerate. Ratan Tata is back as the interim chairman of Tata Sons and will continue to be so till a selection committee identifies Mistry’s successor within four months. Mistry has dug in his heels to fight what he contends is the shabby treatment meted out to him. He has refused to step down as chairman and as a director on the boards of the various group operating companies. He also continues to be a director on the board of Tata Sons.

But Tata Sons and Tata Trusts, which appear determined to do whatever it takes to get Mistry out of Bombay House, have taken a series of measures to oust him. Mistry was replaced as chairman of Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) with Tata Sons’ finance director Hussain; as chairman of Tata Steel with former State Bank of India chairman OP Bhatt; and as chairman of Tata Global Beverages (TGBL) with another Tata group veteran Harish Bhat. Curiously, while Mistry has cried foul and questioned the validity of these board meetings and circular resolutions via which he has been removed as chairman, there has been no legal challenge from his side thus far.

Even as all this happened, IDs on the boards of some group companies have expressed their support for Mistry publicly. They include the IDs of Indian Hotels Company (IHCL), Tata Chemicals and Tata Motors who, in varying degrees, have articulated support for Mistry and the management of the companies on whose boards they sit. IDs of companies like IHCL have explicitly named Mistry, while those in companies like Tata Motors have simply referred to him as “chairman”.

Says Vibha Paul Rishi, a former top executive at Future Group who is an independent director on the IHCL and Tata Chemicals boards: “As far as we are concerned, we have done an evaluation of the chairman [Mistry]. As IDs, keeping in mind the interests of all stakeholders, there was nothing we saw to make us change our earlier evaluation.”

TRADING CHARGES

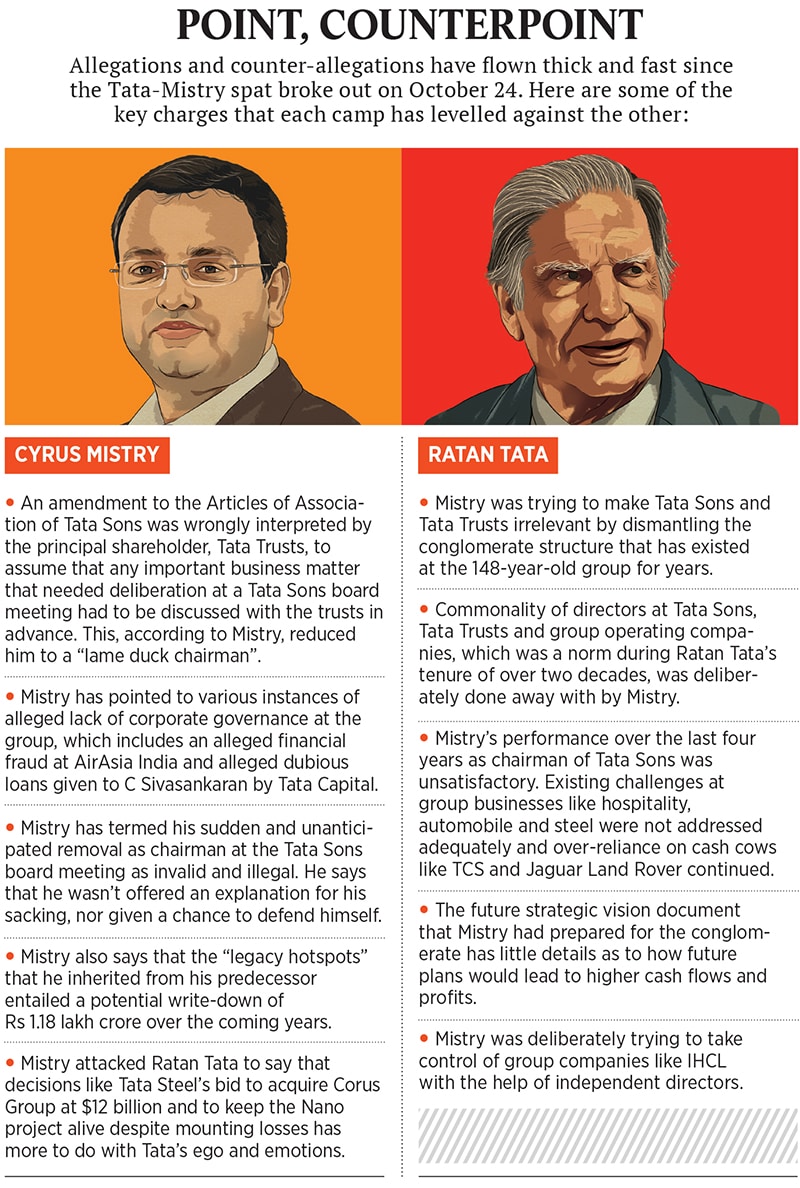

While technical manoeuvres to rid the group of Mistry are being put in place, allegations between the two camps have flown thick and fast and the war of words has escalated by the day.

It began on October 25 with a confidential letter written by Mistry to the board of Tata Sons and the trustees of Tata Trusts finding its way to the media. The missive, which has come to be known as Mistry’s “letter-bomb”, contains some serious allegations. Foremost among them was that Mistry was reduced to being a “lame duck chairman”, with no real authority to do what he wanted to do.

Mistry points to an amendment in the Articles of Association (AoA) of Tata Sons, brought about when he was taking over the job from Ratan Tata, which states that any important business matter that needs to be decided at the level of the Tata Sons board requires the affirmative vote of the Tata Trusts-nominated directors.

A source close to Mistry claims that this amendment was wrongly interpreted to assume that such matters would need to be discussed with the Tata Trusts representatives before they came up for discussion at the Tata Sons board.

He cites an example where Mistry had to meet Ratan Tata and NA Soonawala, also a trustee of Tata Trusts, separately for two to three hours to apprise them of the investment that Tata Teleservices was willing to make to secure spectrum at a government auction. “Mistry had to then repeat the same plan at a Tata Sons board meeting. This was slowing down decision-making and led to confusion regarding Mistry’s role as chairman.”

The Tata Sons source says Ratan Tata was never interested in seeking commercial details from Tata Sons. “He would restrict himself to broader issues like ethics and governance.”

Mistry sought to put in place a corporate governance framework that outlined the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders within the Tata ecosystem, including Tata Sons, Tata Trusts and the group operating companies. This framework wasn’t implemented.

Sources in Tata Sons contend that, contrary to the Mistry camp’s claim that changes made to the AoA tied his hands, they, in fact, diluted the role of the trusts to give him a freer hand. Article 121 of Tata Sons’ AoA earlier said that certain important business matters like the adoption of a five-year strategy for the group’s future growth, which had to be ratified by the Tata Sons board, needed the affirmative vote of all the Trusts-nominated directors. An amendment, put in place in 2014, now makes it necessary for an affirmative vote from only a majority of the Trust nominees, and not all of them.

“There was a clear enough understanding when Cyrus took over about the relationship between Tata Trusts and Tata Sons. The AoA was amended and the role of the nominee directors of the Trusts emphasised. There was no ambiguity,” says the Tata Sons source.

Another contentious issue in the relationship between Tata Sons and Mistry, and perhaps the straw that broke the camel’s back, was Tata Power’s decision to acquire Welspun Energy’s renewable power assets for Rs 10,000 crore. Tata Sons sources claim that while the deal had already been signed by Tata Power on June 12, it was only brought up for discussion at the Tata Sons board meeting on June 30. “This was like a fait accompli for us at Tata Sons. Though we had reservations about the manner in which the deal had been signed before explaining the details to us, we decided to back it.”

However, the Mistry camp has a different view. Sources close to Mistry say the Tata Sons board was “adequately informed about the transaction from time to time” as Mistry did not want to run the risk of Tata Sons voting against the deal at a later stage. Moreover, as chairman emeritus of Tata Power, Ratan Tata would also have received board papers from the operating company outlining the details of the deal. There are several other charges and counter-charges which have been made, with Mistry’s letter and a Tata Sons nine-page response expressing dissatisfaction with his performance forming the basis of these claims. (See box, Point, Counterpoint.)

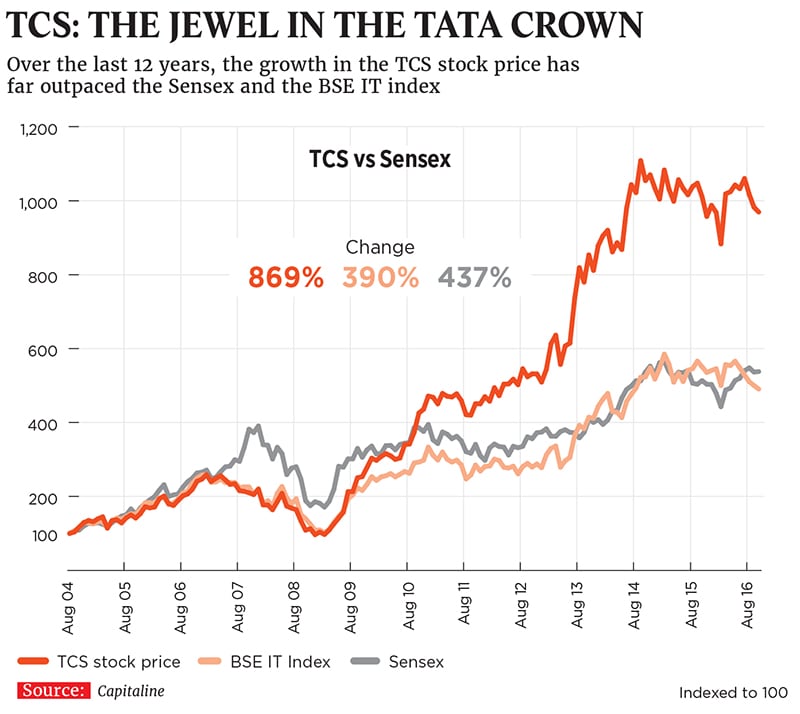

One of the key problems Tata Trusts and Tata Sons face is the group’s excessive reliance on software giant TCS for dividend income. Tata Sons, in its statement outlining the reasons for Mistry’s ouster, says Mistry did not “materially contribute” to TCS’s stellar performance.

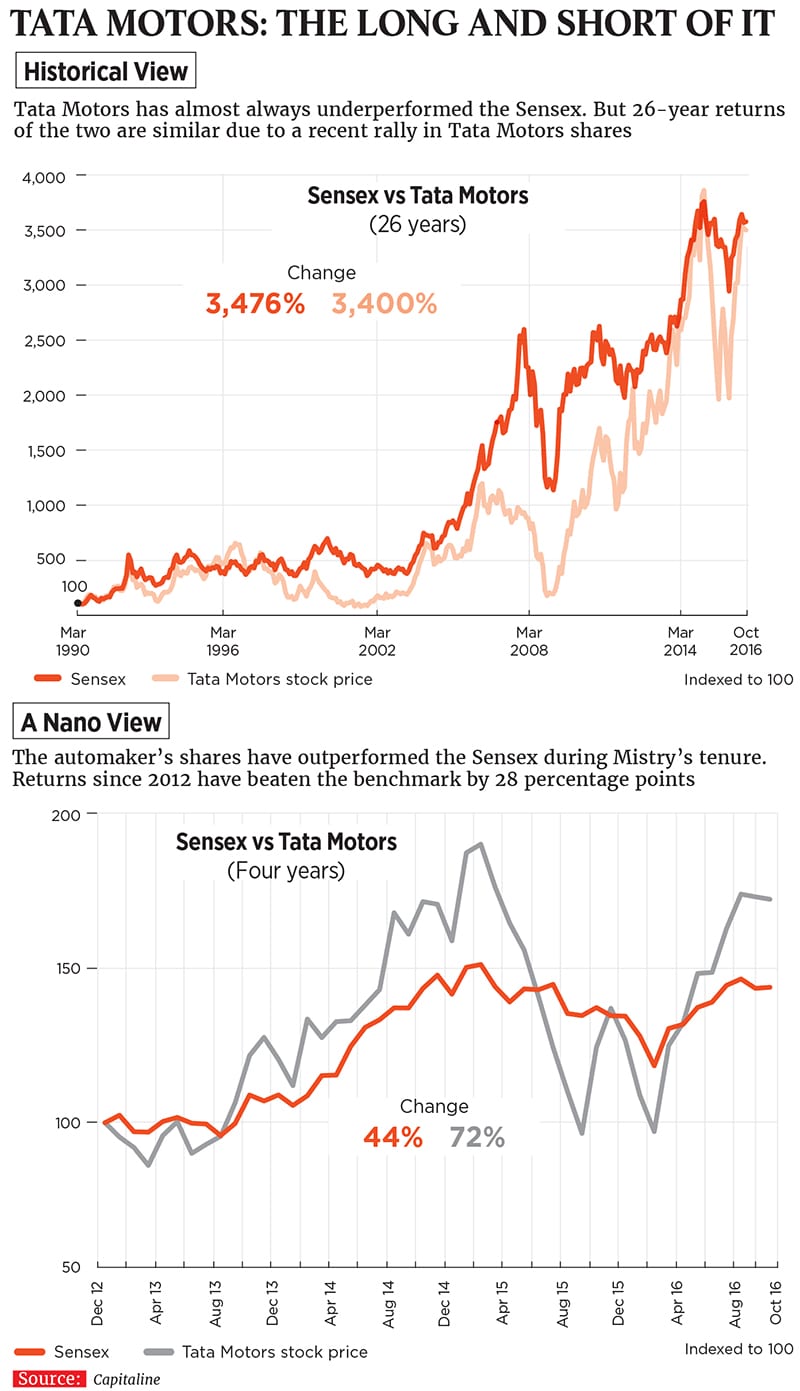

“Dividends received from all the other 40 companies (excluding TCS) have continuously declined from Rs 1,000 crore in 2013 to Rs 768 crore in 2015-16,” Tata Sons says, indicating that other companies, under Mistry’s leadership, didn’t do well enough. Mistry has refuted these charges in a subsequent statement. He says as chairman of TCS, he was actively involved in building global relationships with potential high-value clients “to reinforce the capabilities of TCS for organisations to co-innovate in the digital world”. Moreover, Mistry has contended that “legacy hotspots” like IHCL, Tata Motors’ passenger vehicles business and Tata Steel Europe were inherited by him. He has been trying to address these challenges through measures such as restructuring IHCL’s balance sheet and divestment of assets at Tata Steel Europe for more efficient use of capital.

The view that the group is overly dependent on the fortunes of TCS is also echoed by Tata Trusts.

Says VR Mehta, a trustee of Sir Dorabji Tata Trust: “TCS has an overwhelming share of the dividends coming to Tata Sons. This is dangerous. What happens if the IT sector witnesses challenges? Business patterns are changing.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

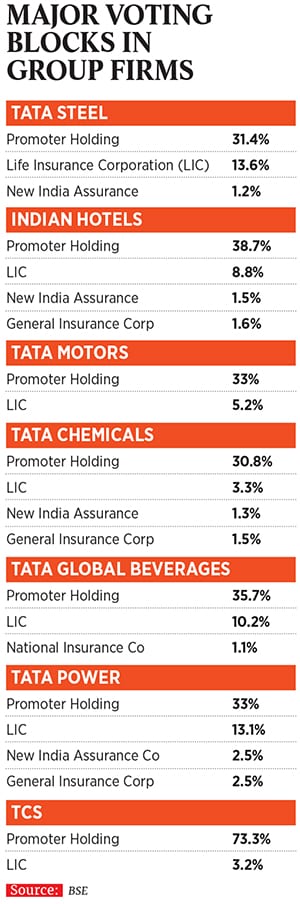

The EGMs will be held from mid-December, where a key role will be played by public financial institutions like the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) which holds significant stakes across various Tata companies. Currently, LIC is keeping its cards close to its chest even as both Tata and Mistry have been actively lobbying for support with investors. Attempts to get LIC’s views did not elicit a response.

The EGMs will be held from mid-December, where a key role will be played by public financial institutions like the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) which holds significant stakes across various Tata companies. Currently, LIC is keeping its cards close to its chest even as both Tata and Mistry have been actively lobbying for support with investors. Attempts to get LIC’s views did not elicit a response.