SaveLife Wants Citizens to Help Accident Victims

Personal tragedy propelled Piyush Tewari to his mission: Provide rapid trauma care to accident victims and save their lives

April 5, 2007, Kanpur: It was a big day for Shivam Bajpai as he had turned 16. As the chirpy lad was walking back from his school around 3.30 pm, a vehicle hit him and sped away. Seconds later, as he lay on the road bleeding, another car ran over him. He crawled to the side of the road asking for help, but to no avail. People stopped to stare, but nobody came forward to help or call the police. Forty-five minutes later, Shivam died.

May 2, 2013, Amritsar: Karan Arora, a 24-year-old who was studying economics in the US, had come down to India for his summer vacation. Along with three friends, Karan set out on a road trip. On the outskirts of Amritsar, he spotted a crowd gathered on the highway, where a mangled car and a bleeding man were lying next to each other. When Karan and his friends decided to take the victim to the hospital, the crowd warned them against it. “Don’t do it, it’s an accident case,” one of them said.

Karan soon found out why, as the emergency room refused to take the “police case” in. While Karan called the police, his friends persuaded the doctor to administer the victim first aid. Almost 20 minutes later, the doctor agreed.

The police arrived another 15 minutes later and started to grill the youths. It went on for 90 minutes till the four called their parents to vouch for their identity. “The victim survived, but the cops and the hospital staff made us feel as if we were criminals. I am not sure if I would ever want to do this again,” Karan says.

His story perhaps reflects the dilemma every aam aadmi faces while helping an accident victim: Dodge police harassment or save a life. Piyush Tewari chose the latter. Not just because he was Shivam’s cousin, but because he wanted to build a social ethos that wouldn’t make humane actions a liability.

The problem

India records one of the highest number of road accidents in the world. In 2011, there was one accident every minute and one life lost every 3.7 minutes. Statistics released by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways in 2011 say there were 4,97,000 road accidents that left 1,45,485 people dead.

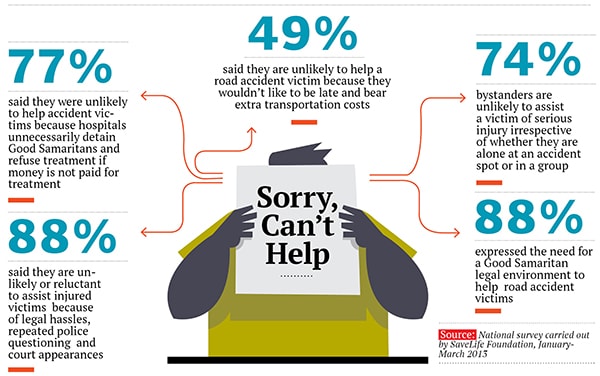

Equally appalling is the chain of events after an accident. Every bystander wants to take a peek, but nobody wants to help even though at least 50 percent of the lives can be saved if the victim is administered basic care within the golden hour (60 minutes after an accident). That’s about 70,000 lives saved every year.

In their book, Indianomix: Making sense of Modern India, Vivek Dehejia and Rupa Subramanya argue that the reasons for our apathy to human suffering are many. We are selfish and busy but, more importantly, we are afraid of a potential liability or harassment by the police. “Human beings are driven by both egoistic and altruistic motives. When you are in a situation where you can help, you might consciously believe that you are saving someone’s life but, on the other side, there is the danger that you might be harassed or even accused in the case,” says Dehejia, an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada.

To assume, though, that Indians are more apathetic than Europeans or Americans would be wrong. The Western world has better legislation in the form of Good Samaritan laws, which indemnify those who choose to voluntarily help a person in imminent danger. “What we have in India are vague directions from the Supreme Court. No one in India wants to deal with cops,” says Dehejia. Here, helping an accident victim is asking for trouble.

The Intervention

Six years after Shivam’s death, Piyush Tewari, 33, his cousin and guardian (Shivam’s father passed away when he was six months old), still can’t get over the tragedy. “His death was avoidable. He kept begging people to take him to a hospital. They didn’t,” he says. After Shivam’s accident, Tewari made several trips to Kanpur to understand the circumstances of the accident and why people didn’t come forward to help.

That’s when the SaveLife Foundation was born in 2008 to create a network where bystanders can offer a basic level of life support to any accident victim.

In May 2011, Tewari, the India head of Calibrated Group, a Los Angeles-based private equity firm, quit his job to focus on SaveLife. He had spent enough time on the ground to figure out the problem. It starts the moment a bystander brings an accident victim to a hospital. “In the medical form, you can just write ‘brought by a bystander’. There is no need by law to mention the details of who has brought the victim in,” he says.

Then why do hospitals ask for such details? To ensure that the police can easily track them to follow up the case. “But at what cost? Letting people lie on the road and die when they can be saved? It is really a decision that the country has to take, whether we amend our laws to allow people to help accident victims or we continue to subject them to the kind of harassment they go through,” he adds.

Laws don’t change overnight, or at least till politicians see a vote potential in it. For the issue at hand, there is almost no obvious political advantage. So one way to get around this problem was to work with the police. In February 2009, SaveLife led a training programme for about 3,000 officers of the Delhi Police. “We partnered with AIIMS, Apollo and Max Hospital. In some time, we started getting feedback that police officers are helping save lives not just in accidents, but even in cases like suicide. That’s when I realised that this idea has a much bigger potential,” says Tewari.

SaveLife now runs a project in Delhi, Noida and on NH-8 in Maharashtra, on the outskirts of Thane district. Early last year, Tewari roped in Religare Technologies to set up a call centre (No: 1800-200-3060) where people could report accidents. The call centre would then send out SMS alerts to all SaveLife volunteers, trained police officers, gas cutters and ambulances, so that people closest to the scene of the accident could rush in.

How They Work

SaveLife has a four-pronged strategy. One, it identifies the most accident-prone areas. Two, it trains volunteers from all walks of life—from police officers to shopkeepers and students. The volunteers are vetted by the police, so they are not harassed later. Finally, the volunteers get incentives—reimbursement of minor expenses and recognition—to help people out.

The authors who studied SaveLife in their book Indianomix believe the real reason why the model clicks is because of the psychological incentives volunteers get in being identified as a hero. The motivation is somewhere between altruism and self-interest. Economists call this the ‘warm glow’ of giving. “Most donations to museums or universities are usually associated with the donor’s name or their family or a relative who’s passed away. Something similar is at work here,” Dehejia says.

However, despite Tewari’s best intentions, this is a merely drop in the ocean. Will his initiative have a national impact? Dehejia says it would be unfair to even expect that. “Local NGOs react to local needs. Like many things in India, where the government has failed, a private initiative is the second-best situation. It is quite possible that someone somewhere else might see the merit of this model and take it up,” he adds.

Tewari himself will not step back even if the future is uncertain. SaveLife is a non-profit and depends mostly on grants and donations. “But we are trying to drastically reduce our reliance on such sources of funding,” he says. The organisation is trying to open up channels of revenue by training people in life-saving techniques in return for a small fee. “Moreover, it’s a time-bound organisation. I hope that my mission will be achieved in five to seven years, after which we won’t need SaveLife anymore,” he says. Tewari also feels his trauma care models are replicable and people can pick them up to learn and implement life-saving strategies in future. For him, his organisation is just the means to an end.

But Tewari knows he has several hurdles to cross before that. His public interest litigation to the Supreme Court for a legal framework that would encourage bystanders to come and help accident victims hasn’t gone far. The court, in its response, has said it is the government’s prerogative to issue guidelines. Tewari also doesn’t like the silence of policymakers in the country. Any letter or appeal or request for a meeting almost always ends in no response. The private sector doesn’t look at road safety as a part of its corporate social responsibility. Nor do insurance companies, despite having big stakes in the game. “They bear the biggest brunt. Insurance companies can refuse to insure people who have drunk driving cases against them or a bad track record of road safety. Last year, all the major insurance companies put together paid out $3 billion in motor accident claims alone,” he adds. SaveLife is also trying to get a short code number (which is easier to remember) for a helpline, but it is pending approval from the government for the last 12 months.

These hitches make him very upset. “You see trucks moving around with rods protruding from the back. In Delhi alone, in the last three years, over 850 deaths have taken place after collisions with such trucks. The government can easily prevent these deaths by mandating that such rods should be moved in covered containers only,” he says. “It is a major embarrassment that we have the highest number of road accidents in the world. We are trying to tackle the issue but the amount of traction we get is 0-1 percent.”

In the last three years, SaveLife has trained about 4,200 policemen in Delhi and 400 in Noida. It has been able to mobilise 1,470 volunteers in Delhi. There are 180 volunteers on NH-8. “We have just been asked to train another 4,600 policemen in Delhi and also have a request from 10 states to train their officers in basic life support,” adds Tewari.

His efforts are showing results. In Delhi, in the last three years, the survival rate among accident victims has gone up to almost 94 percent. In 2008, it was about 79 percent. Moreover, on NH-8, the response time for SaveLife volunteers is an average 7 minutes compared to 15 minutes for an ambulance and about 45 minutes for the police.

Tewari says he is still learning the art of policy advocacy and mobilising volunteers. Every time he feels demoralised, he goes back to why he started SaveLife. “If you look at train accidents or building cave-ins, the first people to help are bystanders. The dimension of empathy changes when it comes to a road accident. There is no way we can live with an approximate 15 deaths per hour,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)