V.G. Siddhartha is Branching Out

Just like he did with coffee, converting a commodity into a lifestyle brand, Cafe Coffee Day's V.G. Siddhartha now wants to convert timber into value-added furniture

In 1983, if someone had told coffee baron V.G. Siddhartha that one day he would own an impressive multi-storied office on Vittal Mallya Road, Bangalore’s tony residential and shopping address, he would have called them crazy. Siddhartha was then just a rookie analyst at JM Financial and Investment Consultancy.

Today Coffee Day Square, his Group’s headquarters, a glitzy glass-fronted building, stands right across UB City from where Vittal Mallya laid the foundation of the multibillion dollar UB Group managed today by his son Vijay.

Siddhartha’s office, occupying an entire floor, has glass walls that offer a breathtaking view of Bangalore. On the day we visit, the founder of Café Coffee Day, India’s largest cafe chain, is waiting by the lift. A strapping tall man, who looks much too young to be 50, he opens the conversation with the typical south Indian greeting, “Have you eaten?”

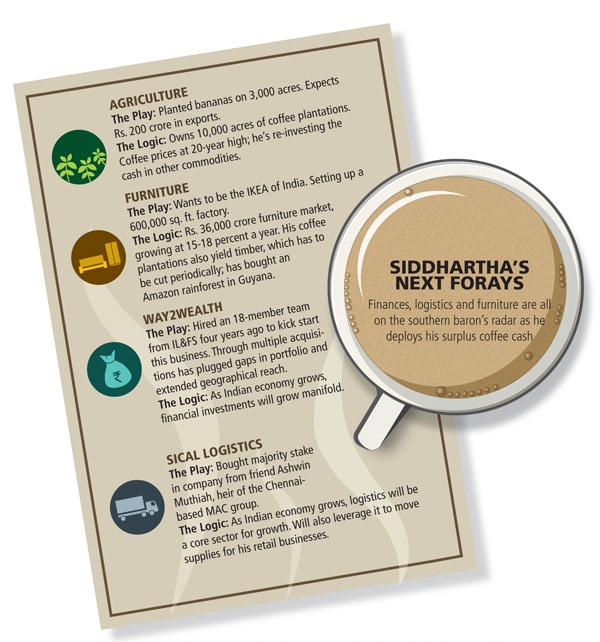

Nandan Nilekani who has known him since the early ’90s, and is a close friend and mentor, describes Siddhartha as a natural born entrepreneur with an uncanny ability to sniff out a good deal. “He is extremely restless and is very quick and decisive. Once he gets an idea, he will quickly go and implement it. He is very methodical and also very big on backward integration,” says Nilekani. Combine that with his ability to work 12-14 hour days, seven days a week and the result is a business empire that straddles retail (Café Coffee Day), financial services (Way2Wealth Securities), venture capital, hospitality, logistics (Sical), land development and now an upcoming furniture business.

Last year Siddhartha brought all his businesses (except agriculture) under a common holding company, Coffee Day Resorts Holdings. The group’s combined turnover is Rs. 2,000 crore to Rs. 2,250 crore. He owns about 10,000 acres of plantations which grow coffee and other commodities. “In the next seven years, at least three or four of these businesses will be doing revenues of $1 billion each,” he says.

But even as his empire stretches and his bets become bigger, Siddhartha remains completely hands on. In the late ’90s, two of his businesses, Way2Wealth and Café Coffee Day (CCD), were both at a crucial stage. This was when the retail financial industry was taking off. It was also the time his father-in-law S.M. Krishna, the present Indian Minister for External Affairs, was chief minister of Karnataka. Friends say that between 1999 and 2004, Siddhartha managed his companies in the day and spent the evenings helping his family look after state politics.

Strapped for time, he had to make the painful choice of focussing on one business. In the next few years, CCD raced ahead and today is India’s largest retail brand. Way2Wealth, on the other hand, lost the battle to Kotak and India Infoline, companies which started at the same time.

Friends say that succession planning — in particular, building a strong second tier of leaders — is on his mind a lot these days. Over the years, Siddhartha has received coaching from global consultants on this. But investors seem to be less concerned about succession issues.

K.P. Balaraj, of Westbridge Capital, which invested $20 million in CCD in 2004 (worth at least five times more today), says that at this stage of the company’s growth, succession is not a burning issue. “No one’s asking Mukesh Ambani this question,” he says.

Last year, a consortium of three private equity (PE) firms, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, New Silk Route and StanChart PE, picked up a 25 percent stake for around $200 million in the holding company. “It is very rare for PE funds to invest in a holding company. Normally, they invest in business directly,” says Balaraj. The funding rounds closed in just two months, and one investor says that the venture capital funds were falling all over themselves to pick a stake.

Siddhartha’s biggest success story till date is Café Coffee Day, which at 1,000 plus outlets, is India’s largest retail brand. He is equally bullish about his other businesses: SEZ, Way2Weath, Sical, and agriculture. “We haven’t done anything great till now, but the next 10 years will be extremely crucial for us,” he says.

His biggest bet though might be on a business that is still below the radar. He wants to build India’s largest retail furniture business. “My dream is to create an IKEA from India,” he says.

Bean to Cup, Log to Wardrobe

The success of CCD has cemented Siddhartha’s belief that a vertically integrated model works. Much like what he did with his cafes, he wants to own an entire chain in furniture.

Almost everything that CCD needs — coffee, furniture, waste management, coffee machines, logistics — is sourced in-house. Siddhartha owns 10,000 acres of coffee plantations. “Today if anyone else wants to match our coffee production, it will cost him or her $250 million to $300 million. Our costs were peanuts,” he says. That is because all the land he bought was when prices were at their lowest.

Hairsh Bijoor, a management consultant, agrees that CCD’s integrated model helps keep costs low. At 1,000 plus outlets, he says, CCD has now become a formidable competitor even for foreign brands like Starbucks. “I don’t see them being able to offer a cup of coffee for Rs. 50 at their outlets without bleeding.”

Siddhartha is bringing the same philosophy to his new furniture business, Daffco.

Coffee grows in shade, and the plantations that Siddhartha was buying each year came with a lot of timber — silver oak, nandi and sal trees — which had to be cut periodically.

Just like he did with coffee, converting a commodity into a lifestyle brand, Siddhartha decided to convert timber into value-added furniture.

Infographic: Hemal Sheth

“We calculated whatever timber we had, converted it into furniture, suddenly it became thousands of crores,” he says. The furniture market is at Rs. 36,000 crore, growing at 15-18 percent every year. “If you believe GDP will grow at 8-9 percent, if you believe construction is going up, where is the furniture going to come from? Once I started thinking like this, the numbers looked mind boggling,” says Siddhartha.

He first experimented with a small 30,000 sq. ft. factory in Chikmagalur in Karnataka and started supplying furniture at cost to CCD. “Twenty to twenty-five percent of a café’s cost is furniture,” says C.K. Nithyanand, director, Daffco.

Two years ago, an American company (Siddhartha won’t name it), which had a 30-year lease on 1.85 million hectares of Amazon rainforest in Guyana in South America, came to him looking for funds. Siddhartha knew that India is a timber deficit country, 70 percent of wood used is imported. He decided to acquire a majority stake in the American company. By now Daffco (the furniture company) was already supplying furniture to his cafes and resorts.

Around the same time, a friend passed him a biography of the IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad. IKEA is the world’s largest furniture company, operating in over 30 countries.

An idea was born. “More than my intelligence, I can pick up ideas and copy them better and faster than others,” he says. It was a chance meeting with the owners of Germany’s largest café chain, Tchibo, in 1994, that first inspired him to set up Café Coffee Day in India.

“At every trip that he travelled abroad, he would closely observe how international chains functioned and then he would come back and try and duplicate that in his café,” says Nithyanand.

Siddhartha is convinced that like cafes, he can create a home-grown national brand for furniture too. He is setting up a 600,000 sq. ft. plant in Chikmagalur that will start supplying furniture in two years.

Siddhartha is talking of millions of dollars of investment here. While a café can be started in a 1,000 sq. ft. outlet, a furniture store size can run into 200,000 sq. ft., at rentals of Rs. 125 per sq. ft. Plus, furniture is a business that is run by heavy discounting.

Ask him if he should have at least tested the waters and set up a few stores before leasing timber or setting up the factory and his answer’s a firm no. “I used to read a lot of research reports, which said you must be focussed on core competence. The experts said that if you are going to produce steel, buy out iron ore; don’t be in the mining business. Today whoever doesn’t have a captive supply of iron-ore is dead. I know that for the first three or four years, retail will lose money, we will goof up in our designs in the early stage. But If I own the timber, I can still survive,” he says.

Others agree with his logic. “The one who controls raw material, controls everything in this business,” says Nithyanand.

Even before a single piece of furniture has been shipped from the factory, Siddhartha has already won a contract to supply Rs. 30 crore to Rs. 40 crore worth of furniture to Home Town, a Future Group company. Mahesh Shah, CEO, Home Town, who was a key negotiator in the deal, says that Siddhartha reminds him of Kishore Biyani, Future Group’s founder: “They have the same intuitive sense for business and are very quick,” he says. “When we were negotiating the rates, his team had come with all kinds of spread sheets and reports and we kept going over the numbers. Siddhartha on the other hand just did the numbers in the head and in a few minutes we had a decision.”

Siddhartha says he knew from an early age that he was good with numbers, “Whenever you go for a negotiation your mind-maths should be so strong, you should know by end of the day whether you want to do the deal or not. You can’t take a pen and paper and start calculating. I can write a five year plan in five minutes,” he says.

That’s a quality not easily replicable. Recently, Sical, the company he acquired in April last year, was bidding for an 8-million tonne terminal in Kandla. Siddhartha realised that Adani had a 120-million tonne terminal just 60 km away. Seeing no point in fighting with such a large player, he asked the team to look at other options like Tuticorin, which was getting coal from Australia and Indonesia. It turned out that Tuticorin would get 18 million tonnes of coal in the next five years. “The team here is exceptional” he says, “all they need to do is think out of the box.”

Letting Go

As his businesses scale up, and he enters his 50th year, people close to him have begun to wonder how long he can continue to manage everything alone. “If he is going to scale up any further, he needs to let these companies operate independently under a strong set of leaders,” says a close associate. He says that Siddhartha is too hands on and like all first-generation entrepreneurs, does not find it easy to let go. “He has this deep distrust of big name CEOs…. He worries whether they will have the same commitment that he has.”

Siddhartha disagrees with the perception that his is a one-man show. “There are 19,000 people in my companies. I have some very capable managers. The reason I can sit here, talking with you for two hours uninterrupted is because of each one of them.”

He says he is consumed with building a strong set of younger leaders, but to say that there is no other talent in the company apart from him is a gross exaggeration. In the last three months, he hired five senior people, who include a head of operations for the cafes, a Human Resources head from Philips, and a general manager from Taj.

Siddhartha, his wife Malavika and two children own 70 percent of the holding company. A president running each business reports to Siddhartha. “Our SEZ business is handled by a team of just 12 people, and they are handling revenues of Rs. 160 crore. I spend only two percent of my time on that.” He says that CCD takes up 40 percent of his time, and his logistics company Sical takes up 20 percent. The rest is spread over other businesses. Shashi Bhushan, the CEO at Way2Wealth, says that while Siddhartha sets the guidance, he doesn’t interfere with day-to-day operations.

“He once told me, ‘I may sometimes forget people who make money for me, but I never forget those who lose my money.’ That was enough motivation for me,” says Bhushan.

Siddhartha’s friends say that his only passion is his work. “His trip in life is not a fancy jet or a big car or even seeing his name in print everyday,” says the head of a large financial services company. A recluse, he rarely grants the media any interviews, and on those rare occasions when he makes a public appearance, he seems ill at ease.

Friends say his wife Malavika, who is a board member and runs his hospitality business, is the complete opposite, an extrovert. An employee who works with her says that Siddhartha reviews her work just like he does any another business unit head, “and is sometimes very tough with her”.

He does business mostly with people he knows well, buying and selling assets either directly from friends or on tips from them. These are the qualities his investors like. “Every time I’ve met him, it is on a Saturday at one of his cafes and not in some fancy hotel,” says Balaraj of Westbridge.

Every month he visits at least 45 cafes and is known to point out minute details to store managers. “That is the reason investors put money on me, not for sitting in AC offices,” says Siddhartha.

He recounts the time he was in Mumbai and used to work in Tulsiani Chambers, Nariman Point, where Dhirubhai Ambani also had an office. “There was just one lift in the building which was mostly occupied. Every day at 9:30 a.m., Dhirubhai would climb up four floors in a suit and tie because he didn’t want to waste time waiting for the lift. And I used to wonder why the rest of us couldn’t do that.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)