Chandra Shekhar Verma: The One Who Sails Against the Wind

Public sector steel giant SAIL needs to shed its historical baggage to remain competitive. And it has got a tough boss determined to do just that

It was not something that a new chairman and managing director at India’s largest steel firm, the Rs. 42,000-crore Steel Authority of India Ltd. (SAIL), would have had the audacity to do. But this September, barely three months into his tenure, Chandra Shekhar Verma refused to sign off on the daily and monthly production targets for the public sector company’s eight plants.

Regional heads pleaded with him to get this routine matter done with, but Verma insisted he would accept targets of no less than 100 percent. Officials maintained it was impossible.

For years, SAIL’s plants had got used to working at 97 percent of their capacity or less. After much debate, Verma struck a compromise with the factory heads: Daily targets at 100 percent and monthly targets at 98 percent.

The message spread across the company like lightning: The new chief was tough, demanding and determined to change the way SAIL had functioned for a long time. The doddering, overstaffed behemoth was due for some fundamental change.

Verma has so far lived up to that expectation. He has replaced the old performance appraisal system with a balanced score card system that demands accountability. He has done away with the practice of promoting people on the basis of the greyness of their hair or their rapport with top management. Now career progression will depend on a set of objective data.

Verma has kickstarted a plan to rationalise the workforce to industry standards. Most retirees will not be replaced. He is also pushing his staff to be result-oriented and not take refuge in red tape.

Despite an ambitious plan to quadruple steel-making capacity to 60 million tonnes by 2020, SAIL had been lax in its ongoing expansion and modernisation plan.

The Rs. 70,000-crore project had been delayed by at least three years. Verma has now come in and speeded up the rate at which work orders go out from the company. The new deadline has been set for 2013.

But all this gives only a hint of the bigger change Verma want to bring to SAIL. The company has been losing is pre-eminence in the market over the years. Its share has shrunk to 20 percent. “I want SAIL to regain the 30 percent market share it had earlier,” Verma says in an interview to Forbes India.

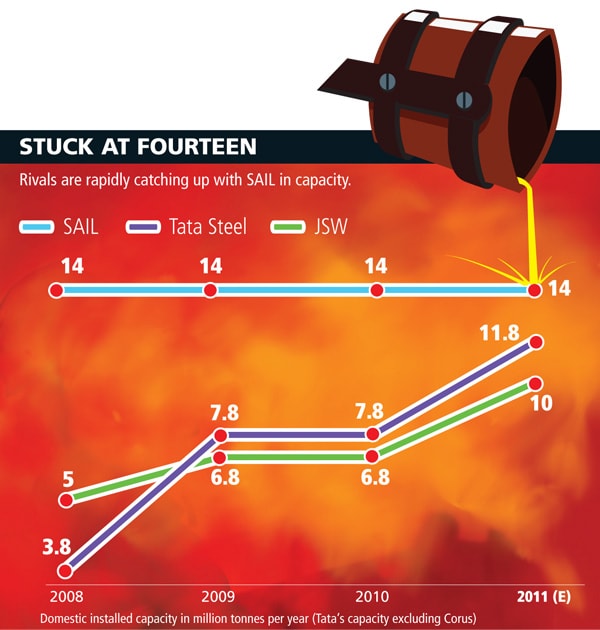

Robust rivals such as Tata and JSW have rapidly reduced the capacity gap. They have added fresh capacity quickly to cash in on surging domestic demand even as SAIL was caught in its own bureaucracy. SAIL needs more agility to stay one step ahead.

It has also lost its status as the price setter. “Earlier, SAIL would set the steel prices for the month and others would follow,” says a trader. But in many markets now... they no longer wait for SAIL’s signal.”

So, when the government began its hunt for a new CMD for SAIL earlier this year, the mandate was to find one who would push through the hard decisions needed to put SAIL back in the game. And the board of directors — which includes former Maruti managing director Jagdish Khattar and economics professor Deepak Nayyar — asked for someone young who could pump in fresh ideas.

In June, the government chose Verma, then the finance head of Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd. (BHEL), for the job from a candidate list of 23. The 51-year-old became the youngest CMD in SAIL’s history. And the steel ministry threw its weight behind him. “He has come with an open mind and is pro-active. We are supporting him,” says P.K. Misra, secretary in the steel ministry.

The proverbial die had been cast.

Man of the Moment

It is not clear whether Verma is an insider or outsider to the steel industry. He had spent 29 years in organisations like BHEL, Indian Railways Finance Corporation, ITI and Delhi Stock Exchange. But as someone who started his career at a small steel firm, Verma had always studied the sector closely. It helped that a tenth of all orders at BHEL came from the steel industry.

At the very first board meeting after taking charge, Verma made an impressive presentation to the directors. “He surprised all of us with his knowledge of the industry. He had a good local and global perspective, especially coming from a non-steel background,” a board member says on the condition of anonymity.

His track record at BHEL was impeccable. “BHEL’s financial health improved under Verma as its finance director. Its turnover has tripled and profits have quadrupled in the last five years,” says an analyst tracking the company. Verma’s initiatives saw the engineering company bag multi-billion dollar orders for seven super critical thermal power plants in the country. He also helped sew up technology alliances with multinationals like GE, Siemens and Alstom.

However, Verma concedes the game is different at SAIL. “BHEL has a 70 percent market share and has a record order book. There is hardly any competition. On the other hand, SAIL has a lot more variables to face — competition, product price fluctuation, raw materials shortage and technological limitation.”

In fact, the complexity at SAIL is much deeper than that. Even though India has emerged as one of the fastest growing steel markets in the world, SAIL’s own expansion and modernisation plan, announced in 2007, has met with a spate of delays. There are various theories. Some blame the leadership change in the steel ministry. Others cite the convoluted tendering process.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

As a result, the bill has shot up from about Rs. 35,000 crore to Rs. 70,000 crore. “At almost $1,200 per tonne, it is much more than the average spend for a brownfield expansion, even after taking account the modernisation investment,” says Ravindra Deshpande, analyst at Mumbai-based brokerage Elara Capital.

The PSU’s reserves of coking coal, a key raw material along with iron ore to make steel, is fast getting over. While its local peers are busy scouting the global market and are picking up mining assets, SAIL is yet to clinch a deal. The rising spot prices of coking coal have had an immediate effect on its bottom line. It led to a 30.5 percent annual drop in net profit in the second quarter ended September. In a recent report, Elara says it expects the balance sheet as well as return ratios to be under pressure for the next two years — till the volume growth from the planned expansions push up profitability. For the moment, Elara maintains a ‘Sell’ rating on the stock.

With frequent changes in leadership — the CMD typically stayed for three or four years only — SAIL could not plan for the long term. It failed to modernise its plans for 25 years even as rivals put up sophisticated plants. The internal systems are not consumer oriented. As a result, it has lagged behind in changing its product mix to suit the market.

The Time is Now

Verma’s task is cut out. Already, India is emerging as the epicentre of sizeable capacity additions, according to a recent report by the World Steel Dynamics, a global steel industry advisory service. “Given its abundant high grade iron ore reserves, low wages…steelmaking capacity additions in India will be prodigious in the next 10 years,” says the report. Global steelmakers like ArcelorMittal and Posco have already joined the hunt in India. A slew of acquisitions and joint ventures are on the cards. “Amidst this hectic activity, SAIL needs to make sure it retains its supremacy. Luckily, with its iron ore reserves and land bank, it is well placed to do so,” says A.S. Firoz, chief economist, Joint Plant Committee, a Steel Ministry-promoted industry body.

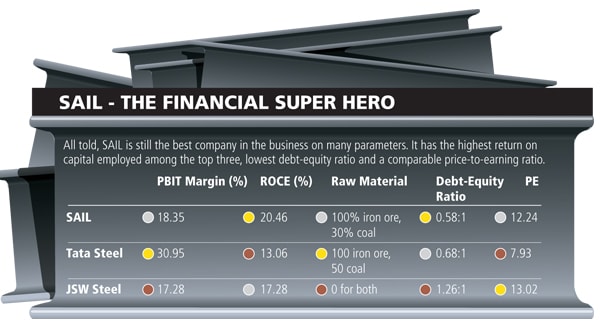

In the meantime, its local rivals, Tata Steel, Essar Steel and JSW Steel, have been responding to the growing demand for value added steel. All these players have modern facilities and the technology to make specialised steel for sectors like the automobile and the construction industry. Today, nearly half of Tata’s Steel revenues come from specialised steel. In contrast, only about 30 percent of SAIL’s revenues come from specialised steel. And till it regains its technology edge and also adds new capacity, value-added steel could well be SAIL’s Achilles Heel.

A few kilometres away from Ispat Bhawan, SAIL’s headquarters in New Delhi, Verma’s bold moves bring back old memories for V. Krishnamurthy. Twenty five years ago, Krishnamurthy had also turned a few heads and evoked a few gasps as the then SAIL chairman and managing director. “SAIL didn’t have any delivery deadlines for its clients. I put in a deadline and also included a penalty in case we failed to meet it. It changed the whole industry,” says Krishnamurthy, the public sector legend who now heads National Manufacturing Competitiveness Council. Under him, SAIL not only turned profitable but also underwent its first major expansion plan since inception.

Krishnamurthy says SAIL did need someone like Verma now. “After spending around 30 years in a company, one comes with a baggage of knowing the system too well. A person from outside can come with fresh ideas and set standards,” he says.

Verma’s first few steps at SAIL have also found support from where it really matters — the steel ministry. His success will depend to a great extent on secretary Misra’s decisions. “In the past, bureaucrats have come and gone and so have ministers,” says a former director. “Unless the bureaucrats also have a long-enough tenure, the continuity in planning and execution is not there.” In fact, Misra is the third bureaucrat at this post within the last one year.

But then, he has two and a half years before reaching the retirement age and that should offer some comfort to Verma. “I intend to be around at least till all the expansion and modernisation projects get completed,” says Misra.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Continuity in the ministry would be a crucial factor in overcoming another serious challenge — buying raw material assets abroad. “If a Ratan Tata or a Sajjan Jindal is convinced of something, then Tata Steel or JSW Steel can go ahead and make the decision immediately. In SAIL, by the time the permission from the ministry comes by, sometimes it is too late,” says a former SAIL top official, now in a private steel company.

His Agenda

Verma’s eventual expansion plan—to reach 60 million tonnes—will also see the product mix change. More specialised steel (over 60 percent of total production from today’s 35 percent) will be produced and sophisticated technology will be used.

SAIL is a very, very overstaffed organisation. It employs 8,143 people per million tonnes of capacity, while the corresponding number for Tata Steel is 3,333 and for JSW Steel is 1,154.

The workforce is being rationalised. Personnel Director B.B. Singh says, “Almost 6,000 people are retiring every year. And if we take in the annual recruitment, the net reduction will be around 5,000. Within the next three years, our workforce will stabilise around 90,000.” And once that happens and capacity increases to 24 million tonnes by 2013, “the same “people will be our strength,” says Verma.

Next, Verma has approached private steel players like Tata Steel, JSW Steel and Essar Steel to set up a consortium to buy assets abroad. While that might take some time, Verma’s main acquisition vehicle will be International Coal Ventures (ICVL), a special purpose vehicle promoted by SAIL, Coal India, NMDC, RINL and NTPC to buy coal assets abroad. Headed by Verma, ICVL has already made couple of bids overseas.

“We have not succeeded yet, but we are already looking at other assets in Indonesia and Australia,” he says. From the present 30 percent, Verma wants at least 50 percent of SAIL’s coking coal needs to be met by own assets.

Verma is giving a fillip to joint venture plans. He is negotiating with Kobe Steel of Japan and POSCO of South Korea to set up specialised steel plants. These plants will be based on new technologies mastered by these multinationals and will help use millions of tonnes of iron ore fines that lie unused on SAIL’s mining grounds.

By all accounts, Verma has just made a resounding start as the head of SAIL. But he would need to be bolder, take bigger risks and have the will power to take the necessary but unpleasant decisions to take SAIL forward. And all the time, he will have to be completely transparent to show his staff that his actions are meant only for the company’s good. And he has a five-year term and a shot at a second-term to do that.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)