Decoding The Detail In Retail

Why there is no need for great celebration or for deep despair over FDI in retail

Much has been said and written about what foreign direct investment (FDI) in retail can do. Depending on which side of the ideological divide is speaking, the assertions are either that it is a magic wand to fix many big problems or that it is a destroyer of honest livelihoods, with little benefits of its own. What is common to both sides is that they are mostly low on fact, high on opinion and generate enormous amounts of confusion. Which is why, we think it is necessary to sift through all of the noise and look truth in the eye. The facts, as we see it, tell us that it has become a symbolic issue, far beyond what reality demands it ought to be; and that there is no need for either great celebration or for deep despair over the idea that FDI in retail is

now a reality. Our analysis tells a fairly straightforward story.

The government has hugely exaggerated the quantum and immediacy of benefits it put on the table to sell the policy—that aam admi consumers will benefit enormously, employment generation will be huge, the country’s supply chain will be transformed and large numbers of small producers and farmers will gain. As things stand, even if modern retail were to take off on all cylinders, these arguments would still not hold water for the next 10 years.

For one, there is the fact that aside from very old markets like America and Europe, in most newly developed markets, modern trade accounts for only 20-25 percent of all retail. India is already at 8 percent—which is significant—but the impact hasn’t been as dramatic as one would have assumed.

Then there is the fact that the economics of the Indian market is such that it makes little sense for global retailers to focus on all consumers. We’re convinced they will focus their energies on the top 33 percent of urban Indian households (a mere 10 percent of all Indian households); investing in the others isn’t quite what they know how to do profitably yet.

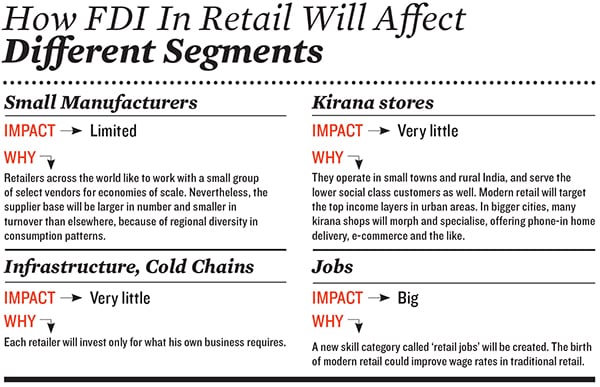

As for small manufacturers, we don’t see that huge numbers of them will benefit. Retailers across the world like to work with a small group of select vendors because it makes for better profitability. So yes, a small number will benefit significantly. And yes, employment will be generated. But it won’t be anywhere close to the numbers now being touted.

Then there is the argument that encouraging modern retail to invest will provide the much-needed booster shot for the country’s dismal supply chain infrastructure. Here again, let’s face it. Retailers aren’t in the business of building national infrastructure. About the only infrastructure they’d be interested in is their last mile.

The only argument that holds true is that kiranas or the small, traditional shopkeepers who are now an Indian staple, will not die. But that is a tribute to the small shopkeeper rather than prescience on the part of the government.

A more honest case for FDI in modern retail would be that it will lay the foundations for a new industry, ‘guaranteed to grow’ for at least the next five decades. Do we need it? The question is rhetorical. Did we need cheaper air travel, more television entertainment, cellphones, air-conditioned cars?

Now that we’ve stated our assessment upfront, we’d like to explain how and why we came to these conclusions.

#1: What will FDI do?

Without doubt, it will immediately save the indigenous modern retail industry that has been built until now. What has been built until now? Between all the modern retailers in India, they now manage to generate Rs 2 lakh crore in revenues—a very impressive number by any reckoning and growing at a compounded rate of 25 percent each year, according to India Retail Report 2012 from Images. But the problem is, most players in the Indian retail business just aren’t making any money yet, and are carrying large amounts of debt, not having had enough equity to fund business losses that are par for the course in the build-up phase of retailing businesses.

Retail businesses guzzle a lot of cash for a long time and then return it handsomely. If not carefully funded with patient capital, of the equity kind, the investment phase can be life threatening.

Kishore Biyani, the largest, most ambitious modern Indian retailer, is a victim of precisely this phenomenon. His business managed to generate Rs 14,000 crore in sales, but in the process incurred expensive and debilitating debt of almost Rs 9,000 crore. Just paying off the accumulated interest was wiping out all the profits the business was generating.

Unable to sustain the business, he was forced to sell a part of it to the competing Aditya Birla Nuvo group, and reduce debt to a manageable amount. However, his business still needs a lot of money to grow to get to serious profitability.

Biyani is not alone. Foodworld, the first Indian supermarket chain, and one that consumers loved, languished at a boutique scale by modern retail standards, with 60 stores mostly in South India, and lost all early-mover advantages and is now a minor player. Shoppers Stop has just 52 stores in 21 years of operations. In contrast, Tesco, for example, has 3,054 stores in just the UK, with revenues of £42 billion in 2011. In India, a country that is so much bigger, all modern supermarket and hypermarket stores put together would not add up to this number.

With the exception of those in the luxury retail business, like Louis Vuitton, Armani or Gucci, the others follow a fairly straightforward model. You buy cheap from suppliers because you buy large volumes. Because you buy cheap, you can sell cheaper to consumers than traditional retailers, who are handicapped because they are small volume players. Ten Food Bazaars, for instance, would buy 200-300 times as much food and grocery than any of the large kiranas.

This is only on the food and grocery side, and does not include fresh produce, which hardly any kirana deals with.

The trouble is that while you build the large volumes that can help you buy cheap, you have to keep fuelling the business with money. You need to do everything right at the stores, including pricing (or front end as retailers call it), in order to attract consumers and establish your brand positioning; and invest in all the support systems needed to run the stores (the back end). It is only when you achieve a certain scale that you pare down the cost of supplies to a point where margins improve and profits begin to come in. Biyani had to sell before he got to this stage.

And then there is the fact that retail is as much science as it is money. For instance, scaling the business isn’t just about expanding across the country by building more identical stores with identical merchandise, but about knowing where to build a new one, when, and how to minimise risk. All of these are lessons global retailers have figured over the years and will bring to India.

To accrue scale benefits, evolved retailers know when to scale by penetrating existing catchments and when to scale by entering new catchments. They also know what is the minimum number of stores they must enter a new catchment with. They know how to tailor the merchandise mix and range to local needs when they build new stores, without messing with the economics or the brand proposition. They have very sophisticated analytics to decide store locations, something we haven’t done well at all in India.

#2: Who’s got the money?

The kind of patient capital that the retailing business needs is not what finds favour with financial investors. It has to come from strategic investors.

Global retailers who’ve already wet their feet in other parts of Asia and the Middle East are the most likely source of FDI into Indian retail. Large global retailers include the likes of Walmart, Carrefour, Target, Metro, Ikea. Incidentally, most of the top 10 retailers in the world are in ‘roti, kapda aur makaan’ (food, clothing and home) categories. Only two do not participate in the food and grocery business at all. They are Walgreen, which is into health and beauty products; and Home Depot, which, like the name suggests, is into products for the home, but with a Do-It-Yourself slant.

The top 10 aside, there are at least 50 smaller retailers who have built distinctive brands and operate at varying price-quality points. They could be inclined to consider India as well.

Our guess is it could be fashion retailers like H&M and Gap, home retailers like Ikea and department stores like Lotte, durables and electronics retailer Best Buy and sports good stores.

Many are already in India—like Zara, Timberland, Marks & Spencer and Body Shop—though they’ve still to shift into high gear despite the potential opportunity (see graphic Who is Coming).

Which begs the next question: Why would they be interested? The answer is not far to find. A large, growing, consumption-driven economy, a slowing down of growth in developed markets, a young consumer base, and a modern retail race that has not even seriously begun yet, is a once-in-a-half-century opportunity. And a consumer who is ready and waiting and underserved.

If we think beyond food and grocery that is served by the ubiquitous kirana stores, we can see all the yawning gaps in the market where the consumer is ready but the retailer is barely present.

As we gadgetise our homes, there is no deep, large national multi-brand consumer durables retailing chain—Croma is still fledgling with 78 stores across 15 cities.

In a country that makes 21 million babies a year, and where seven out of 10 homes have a child at home, there is no deep, large national children’s products retailing chain or even a toys discount retailing chain. There is no ubiquitous national pharmacy chain with store brands for all our everyday ailments.

Do big global retailers have the deep pockets needed to invest and stay the course?

- Walmart most certainly outstrips everybody on this count; it has revenues close to 30 percent of India’s GDP ($421 billion in 2011) and an annual profit of $16.3 billion. But the others are very well heeled too.

- Target has revenues of $67 billion and profits of $2.93 billion.

- In the consumer durables category, Best Buy makes a profit of $1.3 billion.

- Ikea and fashion retailer H&M are hugely profitable by modern retail standards. Ikea makes an annual profit of around $3.85 billion on a $31 billion turnover, and H&M makes a whopping $2.33 billion on a turnover of just $15 billion.

Between the top 20 global retailers, they had a net income of $57.7 billion on total revenues of $1.7 trillion last year. For them, the ‘patient capital’ needed to invest in India is hardly a bother.

Despite a slowdown in the developed world, most of the top 20 have grown their large revenue base in the region of 3 to 9 percent in 2011. They also have the stamina to correct mistakes and start over again if need be. Two examples of this: Puma and Marks & Spencer.

Puma first entered the country in the mid-1990s through a franchise arrangement with Carona. This did not work out and they terminated the agreement and appointed a new franchisee Planet Sports. However, the brand did not have control over the stores or pricing, and this arrangement too failed.

Finally, in 2006, Puma decided to enter directly, with a 51 percent stake and with full management control. The brand carried out some very innovative marketing initiatives, like digital marketing (Puma India went on to Facebook in 2008, a practice adopted by Puma USA later), and controlled the retail environment. Unlike its competitors like Reebok and Nike, Puma went with a mix of 70 percent lifestyle and 30 percent sports performance, which was almost the reverse of its competitors. Apart from all this, Puma appointed a local Indian management, and gave them a free hand. The result: 240 stores and expanding, and a 44 percent growth rate over the last few years.

Marks & Spencer had a similar story. The franchisee opened small stores (average size 3,000 sq ft) and positioned M&S as a premium brand, which led to a disastrous performance. M&S recently entered into a JV with Reliance, where the brand has 51 percent and management control. It repositioned itself, in line with its global DNA, as being a value for money, staples brand. Now M&S is growing rapidly. Stores are also being right sized at about 20,000 sq ft each.

#3: How much money can be absorbed?

Various numbers have been thrown around. Some claim retail can attract FDI in the region of $20 billion. Then there are the more optimistic ones who believe it could go up to as much as $50 billion.

One way to test this wishful thinking and anchor it in reality is to ask how many consumers are out there, where FDI is permitted, with the muscle to buy from these stores when they come in? What kinds of monies are needed to go after this opportunity and turn in profits for investors? And how long would these investors have to wait?

To compute these answers, we looked at nine types of retail formats that form the pillars of modern retail. These include the cash-and-carry format that serves small retailers as opposed to direct consumers; food- and grocery-driven hypermarkets; home; fashion and apparel; speciality stores and so on.

In each category, we compiled a list of retailers with a presence in Asia and the Middle East and hence would want to get into India as well.

Surprisingly, many were already in India either through franchises, licensee agreements, sourcing operations and seemed familiar with the country.

We then looked at some key parameters. These included the price-quality range at which they operate, their strategic market positioning (that is, where in relation to the plethora of competitors do they typically peg themselves), their brand promise, and store formats. Assuming they wouldn’t change their DNA just to get into India, we attempted to assess who could possibly form the consumer base for each format.

- Food- and grocery-driven hypermarkets like Walmart, Carrefour etc, and apparel driven discount retailers like Target, have the ability to target and serve the top 60 percent of urban households by income (which would be the Socio Economic Classes A, B and C of the five point standard industry socio-economic classification, or SEC, system that consumer marketers in India use).

- Other mid-market players (like Bed Bath & Beyond, Victoria’s Secret, Ikea), we believe, will be able to address only the top 33 percent of income earners (SEC A and B).

- Many of the speciality stores that hawk fashion apparel and accessories are likely to be relevant only to the top 10 percent of all income earners (SEC A).

These assessments in place, we tried to estimate how many stores of each kind the top 40 Indian cities could support, given the store formats typically used. We concluded, for example, that a proposition like Ikea can at best set up 30 stores across these 40 cities. As for hypermarkets, we reckon these 40 cities can support at least a 1,000 of them. (See graph The Foreign Investment Inflow)

Based on these numbers, we are convinced there is an opportunity to add another $25 billion in revenues to the $45 billion that already exists. To fulfil the demands this opportunity presents, retailers will collectively need to invest in the region of $12 billion, which includes infrastructure and people.

What it means is FDI in multi-brand retail will be in the region of $7 billion because the government mandates a 51 percent cap on all such investments. And multi-brand retail is where the money and big boys are. Then there is the fact that there aren’t enough malls that can enable business in this format. To build the malls, our estimate is, another $12 billion will be needed—a significant part of which can come in through the FDI route.

If this be the ‘unserved’ market opportunity today, it would be safe to assume the opportunity will be even more robust in the next decade. That is because in nominal terms, the incomes of the top 30 percent in urban India will double in about seven years.

If these numbers are looked at from a holistic perspective, investing $25 billion NOW into retail and real estate gives you the muscle to reach out to a $140 billion market opportunity in the next 10 years. ($45 billion existing market + $25 billion ‘unserved’ opportunity; doubled over the next 10 years.)

#4: Will all these stores get built?

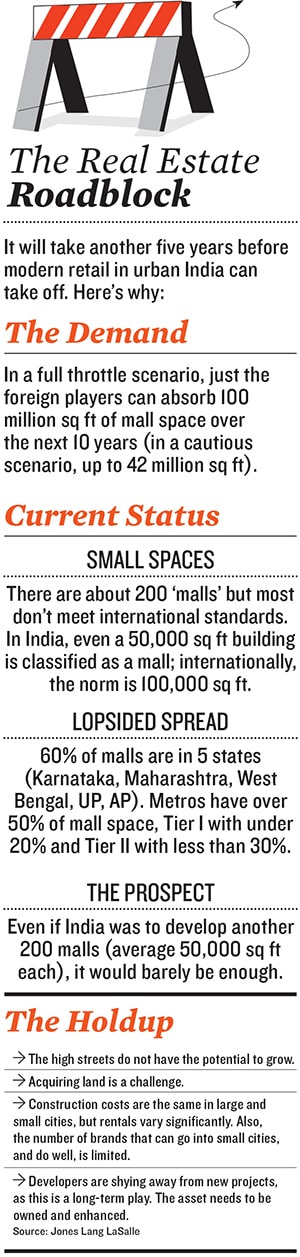

In a perfect world, we’d have predicted very confidently that they would—especially because many of the entrants have been in India for a while in some form and are done with their learnings on the ground. But there is a big hitch to that happening. Hitch is, there is no real estate. And without real estate, all of these investments aren’t possible. It is ironic that consumer demand, historically the bane of investors into India, is ready and waiting, but it is the supply that has many roadblocks.

In our experience, building a mall takes three to four years. Conservatively, that means it will take another five years before modern retail in urban India can go into full throttle.

To exploit this opportunity over the next 10 years, 100 million sq ft of space is needed. A recent Jones Lang LaSalle report says the current stock of mall space is 62.5 million sq ft, only half of which qualifies as ‘superior grade’. They make the point that the inferior grade malls “are essentially ruins of hastily commissioned projects where no retailer wants to set up store”.

As a result, they say, the vacancy in prime operational malls is in low single digits! They argue that retailers, especially large format ones, have been looking for quality space outside malls and retrofitting them. But even these spaces are getting scarce. Several mall projects were announced around 2005 by a variety of developers. But over half have not seen the light of day. Mall developers are realising that malls need to be treated as an asset to be owned and enhanced to suit the retailer’s need and not something that can be sold like other kinds of real estate. This new-found understanding is pushing them away from projects they’ve announced in the past.

#5: What about the SMEs and farmers?

What about them? FDI coming in isn’t going to make life significantly different for most of them. Modern retailers are interested in saving on every bit of cost. To do that, they’d much rather consolidate vendors. Because of regional diversities and state-level differences in consumption and consumer preferences, the supplier base for modern retail in India will be larger in number and smaller in turnover than elsewhere; but even a large hypermarket is likely to have no more than 2,500 vendors, and apparel producers may have no more than 100. They, in turn, will need to benefit from economies of scale if they are to produce at the price, and with the stringent quality parameters that the retailer specifies.

Our estimates lead us to believe that if all the numbers of stores we talked about earlier actually got built, studying the sourcing strategy that global retailers have used in other countries and the number of vendors that some of them have already registered in India, there won’t be more than 20,000 SMEs with turnovers in the region of Rs 50 lakh to Rs 2 crore doing all the job.

An often touted argument is that Indian suppliers can be a source for the rest of the world. The same consolidation logic would work even more acutely in this case. Even if you assume—very unlikely, but let us assume it—that double the number of SMEs will be a part of the modern retail journey, that’s still only 40,000 of them. In a country with 13 million SMEs, this is still a drop in the ocean.

This model of suppliers is analogous to that in the automobile industry where vendors and suppliers are few, but they’re large, and partners in the business. They grow as the manufacturer grows. The vendors on their part may sub-contract their work to smaller vendors. But it is a well-defined vendor ‘orchard’, which yields more fruit over time, but not more trees.

Imports may or may not be a large percent of sales. But a cursory look at non-food goods flooding India from Chinese shores compel us to believe “goods made elsewhere and tailored for the Indian market” will happen, if operations are cheaper and easier to manage from elsewhere in the world.

As for farmers, it is much the same. To supply ‘everyday’ vegetables to the top 40 cities, 2 lakh hectares of vegetable farm will be needed. That is just a small fraction of the 11 million hectares of vegetable farms India has. Two lakh hectares of vegetables need just two lakh farmers. In the larger scheme of things, insignificant again! There will also be large aggregators, if there is benefit in sourcing from small farmers or suppliers, and one kind of middle man will get replaced by another, but hopefully a less exploitative one.

Will the country’s cold chain get established and will granaries get modernised as a result of FDI in retail? Unlikely again because each retailer will invest only what their business needs. To use an analogy, retailers will invest in building the last mile road to their facilities, but are unlikely to contribute to building the nation’s road network. There are some things that the government alone can and must do on its own or encourage through separate policies. FDI in retail will not be the magic wand for preventing things like losses of farm produce due to wastage or spoilage. Just for the record, FDI in cold chains was allowed a while ago. But nothing really came of it.

#6: And jobs?

Investments of $12 billion will generate direct employment of about 700,000 jobs, if you actually add up how many front-end jobs will be created to work in the number of stores that we talked about earlier, and the back-end jobs needed to run the business. Perhaps another 200,000 jobs in the 20,000 strong vendor community that we estimated.

The number of these jobs here will definitely grow as the turnover of the vendor increases, but they will most likely be contract-type jobs—not employees with full benefits, but certainly jobs with a guaranteed pay check and regular income.

More important than the number, we feel, is the fact that a new skill category called ‘retail jobs’ will be created, and every bit of job movement up the value chain is welcome. What’s more, just as NREGA improved wage rates across the board for labour in rural India by setting an inflation-indexed ‘official’ labour rate, perhaps the birth of modern retail will improve wage rates in traditional retail as well.

Will the small retailers, especially the kirana stores die?

The bulk of them are safe because they operate in small towns and rural India and serve the lower social class customers as well.

In newer settlements, there are hardly any kiranas anyway, because the new real estate is too expensive for them. It is inevitable that some will die, and already have, even as domestic modern retail has expanded. However, there will be no mass murder. Many will survive, morph and specialise. And most likely grow profitably from phone-in home delivery services, and e-commerce, and most likely, will start managing the inventory in richer homes proactively.

#7: So what does all this mean?

Despite consumer demand and global retailer readiness, there are many reasons why the investment in modern retail will be what we would describe as ‘slow burn’. Lack of the critical ingredient of real estate is one big reason.

Then, there is the never ending political sabre-rattling around FDI; the possibility that different states will impose different caveats; or that there will be new conditions that make the already challenging path to profitability even more challenging. And finally, there is the structure of consumer demand in India, which is inimical to modern retail.

Modern retail in India is not for the faint-hearted. The economics of the retail business in India is severely challenging because of the structure of demand and the heterogeneity of consumer preferences. There is less money in a given catchment area than in developed markets, because the structure of demand in India is such that many people buy a little bit each and that adds up to a lot. What works in retail instead is if a few people buy a lot.

This is a problem for two reasons:

- Sales per square foot

- Gross margin return on investment per square foot.

India scores poorly on both, also on account of real estate prices. Unfortunately, solving the problem by going to far flung locations on the outskirts of a city is not a viable option because public transport is poor and fuel is expensive. The retailing model in America was built when gasoline was cheap, and personal cars comprised the central nervous system of that country for a long time. That is not the case here.

Another enemy retail faces is the heterogeneity in India. Every hundred-odd kilometres, there are different oils, different pulses, different brands and different water conditions, to name just a few. This makes scaling the business harder. As one retailer said, when we went from Chennai to Pune, it was like going to another planet!

The SKUs (stock keeping units, or items for sale) needed even for just cooking is a lot. In markets with dismal mom-and-pop stores dominating retail, the consumer automatically runs towards the organised retailer.

In India as we know, the so-called mom-and-pop retailer is a very savvy businessman, and has customer relationship management skills and service levels that are very hard to beat. If value is (benefit minus cost) as perceived by the consumer, then creating the value advantage over the local small retailer costs money too.

This does not mean that there is no money to be made in organised retail in India. It just means that it takes longer, needs harder work, and is not for the faint-hearted.

All of this will combine to dilute the actual investment to less than half of what the market opportunity can support today.

While this may seem like an opportunity lost, it also opens up the possibility that many local businessmen will take a shot at entering the fray, learning this business with foreign partners, and we may eventually see the emergence of entirely homegrown retailers.

The other thing that is clear is this. Over the next five to 10 years, the strong foundations of a new industry with enormous potential will get put into place; new skilled and semi-skilled job categories will be created; a set of new decent-sized supplier companies will emerge; huge joint ventures will be forged; and a model for large corporate ‘middlemen’ buying directly from farmers and transmitting consumer preferences to them will be established.

So let’s reality-check the wild hopes and discount the alarmism, and get on with the job of building one more good thing for the future. It will not be the cure for all ills, but it certainly is one more remedy that needs to be given its best shot.

Rama Bijapurkar is an independent market strategy consultant; R Sriram is an entrepreneur who co-founded Crossword; S Raghunandhan has extensive operating experience in retail and mall development businesses. They work together under the brand Next Practice Retail to offer business design and consulting services for retail oriented consumer businesses

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)