Finolex Industries: Building a New Identity

Prakash Chhabria has taken his father's legacy to a new level by turning a commodity-based business into a consumer-facing one

A look-alike of superstar Rajinikanth strides onto a dusty cricket ground, clad in a traditional lungi, armed with a solid pipe instead of a cricket bat. Requiring an impossible 60 runs to win off the last ball, the actor exhorts several players to bowl at him simultaneously. Brandishing the pipe like a sword, he dispatches the deliveries hurled at him over the boundary ropes and wins the match, obviously, emphatically yelling in classic Rajinikanth fashion: “This is the leader’s style to bring a miracle, let me remind it.”

This was the television advertisement for one of Finolex Industries’ core products—PVC (polyvinyl chloride) pipes, used extensively in agriculture and construction. Conceptualised by its executive chairman Prakash Chhabria, it aimed to ride a cricket-crazy wave when local team Pune Warriors made its debut in the Indian Premier League 2011. (The franchise was terminated by the BCCI in October 2013 over payment defaults.)

Chhabria is not an advertising guru. The 50-year-old is just an astute businessman who seems to have identified a successful model—a consumer-facing approach—for his pipe-manufacturing business that has attracted the attention of big fund managers and investors in India. In just a few years, Finolex Industries has shifted from being a commodities-linked PVC resin maker to becoming a value-added pipes and fittings manufacturer, with a clear focus on the retail segment and expansion plans to far-flung parts of India, where irrigation and housing needs continue to grow.

In 2012, he took charge as executive chairman from his father Pralhad Chhabria (84), and is eager for people to understand what he does. During the course of an interview with Forbes India, Chhabria picks up a marker, quickly draws two blocks to indicate segments of his businesses—resin and pipes—on a large board in his conference room. He then sketches water flowing through a range of pipes and fittings. After that, Chhabria pens the map of the country, pointing to where he wants to expand, from Finolex’s traditionally strong markets of western and southern India to the eastern and north-eastern parts.

Till 2008, Chhabria was concentrating on resins, a raw material for pipes, but then decided to go to the front end. “Finolex was predominantly a resin producer and seller. But we soon realised that growth and scalability lay in the finished product. The dimaag ka kick [spur to the brain] comes from the pipes segment, which is the bigger market,” Chhabria told Forbes India at his factory in Chinchwad, the north-western neighbour of Pune city.

The marketing push aside, Chhabria also innovated on the payments system with the dealers. Finolex has become one of the few Indian firms in the pipes business to get advance payments, which means it does not operate on credit. This keeps the company’s working capital low and returns high, analysts say. “This is a unique case where a company created a brand out of a commodity business,” says Nimesh Shah, co-founder of Enam Securities. Typically, advance payments are seen in the FMCG and two-wheeler businesses where companies such as Hindustan Unilever and Hero MotoCorp command a high premium for their brands.

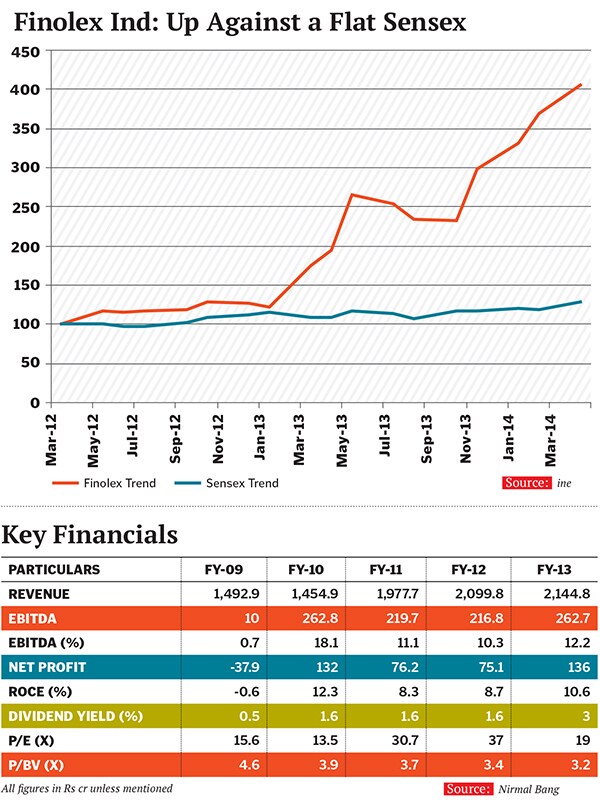

For a company making essential but unglamourous products such as pipes and fittings, the buzz around its business is both unusual and noticeable. The Finolex Industries stock has caught the investors’ fancy with some of the major mutual funds buying it for their midcap funds. Over the last 13 months, the share price has moved up by 154 percent at a time when the BSE index returned only 10 percent.

A Partitioned Childhood

Like many manufacturing businesses that emerged during India’s independence, Finolex has a slightly divergent beginning. The Chhabrias, a Sindhi entrepreneurial family, lived in Karachi prior to Partition. Pralhad Chhabria was forced to start working in his early teens at a small cloth shop there in the 1940s, after the family lost much of its ancestral wealth to huge financial losses in the commodity markets.

The senior Chhabria had worked his way up the hard way, from a cleaner at a wholesale cloth shop to a collection agent. In 1945, the entire family, including Pralhad who had just six rupees in his pocket, left Pakistan for Bombay to make a fresh start.

After initial forays into small-time businesses, Pralhad, with younger brother Kishan, decided to shift to Pune and set up a trading firm in electrical accessories. That was the short-term plan—they were both eager for bigger goals. “During the day I was busy working, respected by customers and suppliers, high quality standards and my sincerity. But at night, I would return home and once again be the child whose opinion was disregarded [by family elders]. My mind was constantly searching for options,” Pralhad recounts in his autobiography There’s No Such Thing as a Self-made Man.

He realised there was more profit in making cables than trading in them, after bagging a sizable order in the mid-1950s from India’s defence department, for wire harnesses for trucks and tanks. This solidified their decision to move into manufacturing, and after several rejections they got an order worth Rs 3 lakh to lay flat copper braiding on the cables used in military tanks. This involved importing a braiding machine from Japan, for which Chhabria got a loan from the Central Bank of India “simply because I was a Sindhi” and the bank was confident of getting its money back, with interest.

Before establishing the Finolex brand, Pralhad and Kishan bought a plastic extruding machine, in which an input of plastic produces ready-made cables, rods, tubes and pipes. After the Second World War, PVC had become more widely used material than rubber. But India was importing PVC cables from England and Germany because local cable makers made only rubber cables. With the new machine, the Chhabrias became one of the first to produce PVC cables in India in 1959.

The name Finolex was coined later that year—after securing and delivering several orders—by the entire family at the dinner table, combining ‘fine and flexible’ wires.

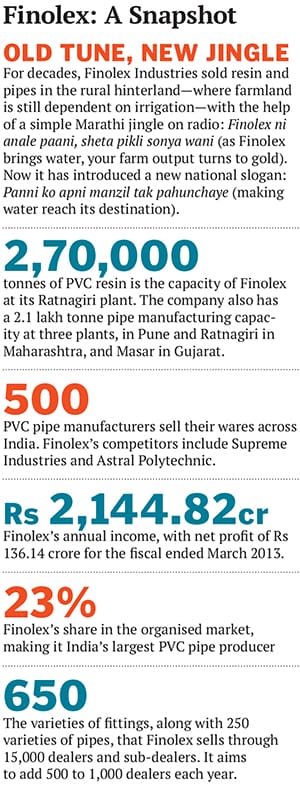

Finolex Cables is now India’s largest cable producer while Finolex Industries is second only to Reliance Industries as a PVC resin maker.

TRANSFORMING ITSELF

“Finolex Industries is undergoing a transformation,” says Jignesh Kamani of Nirmal Bang Securities, as it has moved its business model from B2B (PVC resin) to B2C (PVC pipes). Gautam Trivedi, who heads equities at Religare Securities, agrees: “The perception of the firm has transformed. It was seen as a raw material commodity producer but is now more a finished goods producer. And it has a transparent balance sheet, where debt is coming down, even as the company continues to grow.”

Finolex Industries has managed to reduce its debt due to healthy cash generation. Its total debt for FY2012 was Rs 1,200 crore, which fell by nearly 30 percent to Rs 850 crore in FY2013. Although the chairman did not give any details, he is confident of reducing debt further in the fiscal ended March 2014.

The company’s shift in focus from raw materials to finished goods requires strategy and planning. For one, currently, part of the PVC resin produced is consumed in-house, while the rest is sold in the market. All future expansion will be in the PVC pipe business only and, as a result, the captive use of PVC resin is expected to increase, Kamani says.

For this, Finolex needs to expand their network of dealers and sub-dealers. “And to increase the dealer network we needed to add to the sales force,” Prakash Chhabria says. “Even if one part of the chain malfunctions, the entire process can come to a standstill.” Finolex takes about six months to build its dealer network in a medium-sized state. This is how they expanded outside of Maharashtra, into southern states, district by district.

And then, “we moved in with advertisements, radio jingles and newspaper publicity to create awareness,” says Chhabria. Finolex Industries has spent close to Rs 50 crore in the past five years on advertisement, promotions and travel to expand its dealer network.

DEAL WITH US

Since 2008, amid wide price fluctuations for raw materials, Finolex Industries decided to introduce an advance payment system. “It was becoming very difficult to cope with each dealer’s demand for stocks and credit. We brought everyone on par. Hence dealers had to pay in advance. But what I gave in return was the best quality of pipes,” Chhabria says.

Finolex collects cash faster from debtors at an average of six days in a year and pays its creditors at an average of 32 days. This gives it complete control of its working capital cycle. “[Operating without credit] speaks volumes about the brand itself,” says Nehal Shah, an analyst at Antique Stock Broking.

Raju Desai, 47, who owns an exclusive Finolex dealership, Bharat Pipes in Belgaum district of Karnataka, has little problem with advance payments. “Their strategy has worked,” Desai told Forbes India. He has seen his annual revenues swell to nearly Rs 27 crore in 2012-13 from Rs 45 lakh in 1987, when Desai’s father first met Pralhad Chhabria.

At the ground level, the bullishness is clearly long-standing. But it is only over the last one year that investors began to gain confidence in Finolex. Since it imports its basic raw material—ethylene dichloride, vinyl chloride monomer and ethylene—it needs to take a significant amount of forex exposure. In 2007, it bought structured derivatives and suffered losses, which hit its balance sheet. Shah says Finolex Industries incurred losses of Rs 450 crore over the last six years, of which Rs 180 crore was due to derivative transactions.

In early 2013, rating agency Crisil downgraded Finolex Industries’s rating due to its forex exposure where there was a considerable amount of unhedged buyers’ credit, which was beyond its working capital requirement.

“We have around 30 percent of our exposure that is unhedged. But we are now very careful about forex risks. We don’t want to go for a complete cover because there are obvious costs attached to a fully hedged position, which we can do without as of now,” says Finolex Industries Managing Director Saurabh Dhanorkar.

FAVOURABLE DEMOGRAPHICS

Finolex will continue to penetrate further into newer regions of India, particularly across north and north-east India. “We are only at the tip of the iceberg,” Chhabria says. The company is betting on the fact that only 40 percent of farmland in India is irrigated (the balance depends on rainwater).

A continuous depletion of water tables across the country has forced people to source water from far flung places.

Despite slackening economic growth, the Indian government has plans to allocate Rs 2.3 lakh crore on water management and Rs 5 lakh crore to the irrigation sector, in the 12th Five-Year Plan (2012-2017).

Besides agriculture, Finolex has improved its focus on the construction business and expanding its network. India has a total housing shortage of around 2.2 crore units in the urban sector. One unit in an urban area consumes 200 kg of PVC products like pipes, flooring, doors and windows, according to the FICCI-HSBC Knowledge Initiative data for 2013.

“People keep complaining about the government and lack of reforms. But villages have been lit up, there is electricity, telecom mobility and better infrastructure. It is better to ride on the bandwagon and grow instead of sitting and complaining,” says Chhabria.

STRONG FIT FOR PIPELINES

Analysts tracking the stock estimate that even as macro-economics favour Finolex Industries, margins in the PVC resin business too will remain firm, with improving market share aiding margins too.

Besides pipes, Finolex has started focusing on pipe fittings–they connect pipes and help water distribution—only recently, with a 1.3 lakh square feet warehouse (India’s largest) for PVC fittings at Chinchwad.

Pipe fittings is a high margin business compared to pipes, and Finolex is now in a position to leverage its strong distribution network and reach, analysts say. Finolex derives only 8 percent of its PVC pipe segment revenues from fittings compared to around 20 percent that rivals Supreme and Astral Polytechnic derive, says Kamani of Nirmal Bang Securities.

Kamani expects Finolex to boost the share of its fittings business to 12 percent over the next two years, thereby increasing the margins of the segment. Analysts also expect near-term margins for PVC resins to improve, as prices will remain firm.

Interestingly, Finolex Cables, another group company that owns 32 percent of Finolex Industries, has also become a stock market favourite. Finolex Industries also owns 14.51 percent stake in Finolex Cables.

Does the stellar performance point to continuing steam in the Finolex Industries stock? Going by the fact that prominent funds like HDFC and Reliance Mutual Fund are showing a deep interest, at present the future looks good. Besides, Warburg Value Fund, a big international investor, owns 3 percent of the company.

The stock price may have risen rapidly, but Chhabria believes he is not even done with his first act. He is confident that the financials will take care of themselves, if they continue to keep the principles simple: “We make pipes. There are some things whose designs do not change. In a business that has no glamour, we do something that other people cannot do for you. We keep you alive by getting you water where it is required.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)