Hyundai's 'sunshine car' Santro drives into sunset

Few expected Hyundai's compact car to succeed. It did more than that. And now, as it gets consigned to history, here's a look back at its role in transforming the Indian automotive market

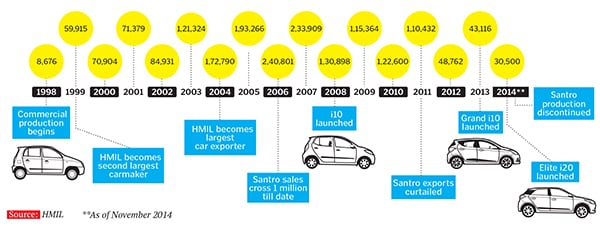

In November, Hyundai Motor India’s manufacturing facility at Sriperumbudur near Chennai witnessed a historic and poignant moment. Around 16 years, 1.9 million cars and over 500 variants later, Hyundai’s ‘sunshine car’—the Santro—undertook its final journey across the assembly line before driving into the sunset.

This was a moment worthy of note, not just for Hyundai Motor Company (HMC)—after all, it was Santro’s success that established the Korean chaebol’s presence in India—but also for the country. Consider that the Santro, with its cutting-edge technology and boundary-pushing features, forced competitors to follow suit and, thus, rapidly modernised the compact cars produced/sold in India. Its success demolished the myth that Maruti Suzuki’s stranglehold in the Indian entry-level car segment was impregnable and converted what was till then a predominantly sellers’ market into a buyers’ one. Santro also established India as a global small car hub and showcased how the ‘Made in India’ tag could be worn proudly, even when it came to a technology-heavy sector like automobiles.

Not surprisingly, discontinuing Santro was a tough decision for Hyundai Motor India Limited (HMIL). And this was not mere sentimentality. After all, Santro still sells over 30,000 units a year. “Santro redefined the compact segment. The product built remarkable trust in the technology, design and safety with its customers. It has been one of the strongest brands in our portfolio till now,” BS Seo, managing director, HMIL, tells Forbes India. But automotive technology and design philosophies have evolved since Santro’s launch in late 1998. “Almost every part in Santro is relatively outdated today and we have also embraced a fluidic design philosophy across all segments. Continuing Santro will fly against our own mantra of offering the best to Indian customers,” points out T Sarangarajan, vice president (production), HMIL. So the decision was made. “Now it is time to bid farewell to this iconic brand,” says Seo.

Strategically, however, HMIL had been preparing for this day. This farewell, therefore, is not a bitter one. Over the last few years, the company has built a strong compact car portfolio, comprising Eon, i10, i20, Grand and Elite i20, which cumulatively offers it a strong 21.8 percent market share (as of the January-October 2014 period) in the compact car segment. Santro’s sales, which touched a peak of 2 lakh units in 2006, have since declined. It sold 43,000 units in 2013 and little over 30,000 units in 2014.

Santro, then, is leaving in the best possible way: Without a fuss. And Hyundai will be better off because it existed.

That is an outcome few had believed possible when Santro was first introduced.

Creating Believers

In 1996, when HMC announced its foray into India with an initial investment of $600 million and a plan to enter the compact car segment, not many took it seriously. Most people expected the company to fail. “They followed a contrarian approach. While Ford Motor Company and General Motors focussed on bigger cars, Hyundai, a relatively unknown player, chose to bring out a compact car. Though it was the largest segment in volume terms, it was the most competitive as well,” recalls Jagdish Khattar, who was the managing director of Maruti Suzuki, India’s largest carmaker at the time Santro was launched. His company had a formidable 80 percent market share in the overall car industry in 1998.

But HMC looked at the challenge differently. “We saw an opportunity in a growing market which had just two major players—Maruti and Mahindra & Mahindra. If we were to bring in the right product, it would work,” says Young Jin Ahn who was then general manager handling the southern Indian markets at HMIL. (He is currently executive director, sales & marketing.)

Initially, HMC toyed with the idea of bringing in its fast-selling compact car in Korea—Atoz—to India. “We dropped that idea as its design was far too radical for the Indian consumer’s taste. It was instead decided that we would tweak Atoz’s design,” says BVR Subbu, former president of HMIL and one of the first employees of the company. Of course, the re-designed model was put through multiple iterations before it was finalised.

Simultaneously, there was another debate heating up within HMIL. This was the one regarding the name of the compact car. The notion of retaining ‘Atoz’ was quickly dropped. It sounded too similar to ‘autos’, or the ubiquitous three-wheeler—not a welcome confusion in the Indian context. The top management of HMIL and their partners from multiple advertising agencies were grappling with options when someone suggested that it should have a tone as fashionable as, for instance, Saint Tropez, the elegant city in the French Riviera. “The city is actually pronounced San-tro-pez, and that led to the creation of the name Santro,” says Subbu.

The christening done, HMIL stayed focussed on offering a product that could break the dominance of Maruti in India. The product would have to be substantially better than what was available in the market. A superior customer experience backed by cutting-edge technology at an affordable cost was identified as Santro’s USP. “We decided to fix the specifications of the car by working backwards [from the USP],” says Subbu.

The compact cars in the market then—Maruti 800, Maruti Zen and Daewoo’s Matiz—were inhibited by cramped spaces; getting in and out of the car proved difficult. Santro’s tall-boy design tackled this and gave the car a spacious look and feel. “Our criterion was that a large man with a turban and a woman in a sari should be able to ingress and egress comfortably,” says Subbu. The rear seats were modified many times over before arriving at what they believed would suit Indian customers better.

Similarly, the air-conditioner was tested in the high temperatures of Rajasthan for four months continuously. Ground clearance was kept high taking into account the flooding of Indian roads during the rains. And side impact bars were provided to enhance safety.

Santro’s power train (engine) and gear specifications were frozen by adopting what Subbu calls the “Peddar Road Syndrome”: The engine torque should be such that it can carry five people with the air-conditioning running on a monsoon day. And all of this in Mumbai’s infamous Peddar Road traffic, with minimum gear changes.

On the technology front, HMIL embraced a multi-point fuel injection system even as other manufacturers, worried about the quality of fuel, took to carburetors. “We knew that it would take time for the fuel quality to improve. We engineered the injectors by adding multiple holes so that the fuel flow does not get choked by impurities,” says Sarangarajan, who joined HMIL in 1997 and initially worked in the quality department. Santro also sported an electronic control unit (ECU) and sensors.

Even as it packed many layers of modern technology into Santro, HMIL understood the need to be cost-competitive. “To succeed, we had to attain a cost structure similar to that of Maruti,” says Subbu. For this, a high level of localisation was critical. HMIL identified the best suppliers and began implementing a single vendor system (another first at that time) which brought in economies of scale and lowered the per part cost. “We promised the supplier a particular volume. If we failed to achieve it, he would be compensated and if we exceeded it, he would give us a discount,” says Subbu. By the time production started, Santro had locked in 74 domestic suppliers and 14 Korean joint ventures in India. “We started with a localisation level of 90 percent. Barring ECU, sensors and a few other inputs, the rest was sourced locally,” says Sarangarajan.

Including its brand ambassador.

Building Brand Santro

As Santro was being put together, HMC had begun to correct a major weakness—a lack of awareness of the brand among Indians. This was not just the case with the common man but also with corporates and advertising agencies. “We had to go from one advertising agency to another, asking them to take our account. No one had the time to look at us,” says Subbu. Consider that the company’s calls for applications for dealerships were answered by barely 300 mildly serious applications.

The need of the hour, felt HMIL, was a brand ambassador. Enter Shah Rukh Khan. The Bollywood actor was an obvious choice for his energetic and youthful presence but he, too, had not heard of the company. “We had a tough time convincing him to take on the role. But once he learnt about Hyundai and its products, he came on board in 1998,” says Subbu. Subsequently, a series of advertisements were released, first introducing Hyundai and then the Santro. Getting Shah Rukh Khan was a masterstroke. His connect with the audience gave Hyundai a perfect platform to create awareness, says a former head of an advertising firm who wished to remain anonymous. The actor continues to be the brand ambassador for Hyundai even today.

Santro was launched on October 9, 1998, at a price starting from Rs 2.99 lakh and was made available simultaneously through 74 dealerships across the country. It was the first global launch of a car in India. The car’s tall-boy design had varying, often extreme, reactions. While some termed it modern, many found the design awkward and felt it resembled an auto. “We expected this and had a plan. If we got the people to experience the car, they would start liking it. So we started a test drive campaign,” says Ahn.

And it worked. People began to buy into the idea—and the car. “Despite its unconventional design, Santro was a well-rounded product with a very strong and smooth engine, spacious interiors, superior fit and finish and cutting-edge technology,” remembers Hormazd Sorabjee, editor, Autocar India. “I had called it the Ambassador of hatchbacks for its spaciousness then.”

Sales began to accelerate after an initial lull. Within six months (in March 1999), HMIL became the second-largest car manufacturer in the country. In January 2000, Santro overtook Zen for the first time, and in November that year, HMIL rolled out 1.5 lakh cars (25 months after its launch).

By November 2006, a million Santros were on Indian roads. And as of today, 1.4 million units have been sold in India alone (Santro was sold in over 100 countries.). Such was its success that HMIL achieved cash profit within 12 months of sales, commenced the second shift of its manufacturing facility in 2001 and began preparing for a capacity expansion.

Meanwhile, Maruti’s fortunes took an irreparable hit.

Inevitably, the rise of Santro ran parallel to a fall in the Indian auto giant’s market share. From 80 percent in 1998, Maruti’s share dropped to 60 percent by the end of 1999; it fell to 45 percent in 2000. “Consumers saw Santro as a modern product compared to Zen, which was 10 years old, and an even older Maruti 800,” says Khattar. “Due to various reasons, we could not launch new products in time. WagonR, on whose tall-boy design Santro was based, entered India much later than the Korean car.”

Santro’s success and its own eroding market share saw Maruti advancing the launch of WagonR but it suffered due to high import content (which made the car costly). Market dynamics forced it to price the car aggressively and, thus, incurred losses for every car sold. In 2000-01, for the first time since it was set up in 1981, Maruti ended with a loss—of Rs 269 crore.

Santro’s continued success was also on account of HMIL’s drive to push the envelope on standards. This enhanced the perception of the company as one that produces high quality cars—and one that is a trendsetter. For instance, when Santro was launched, the company knowingly kept the price differential between the air-conditioned and the non air-conditioned variant low—at a few thousand rupees. HMIL was projecting air-conditioning as a health necessity. “Barring Kashmir and Shillong, all other places saw strong sales of the air-conditioned variants,” says Subbu. Other carmakers followed suit and air-conditioners became a standard feature.

When the Supreme Court advanced the schedule for introduction of Euro II cars in Delhi in 2009, HMIL moved in quickly and launched Euro II Santro even before the deadline. Maruti, on the other hand, could not come up with a Euro II variant in time and, in the process, was unable to sell a single car in a market that then accounted for 20 percent of national sales.

HMIL set another benchmark when, on the eve of Santro’s first anniversary, it suddenly announced an extended two-year warranty for its cars. Other carmakers had to follow suit and extended warranties, too, became par for the course.

As domestic sales crossed 70,000 units, Santro became export-competitive in terms of quantity. “The quality was already at levels similar to that in Korea, so we began to export in 2000,” says Sarangarajan. Exports initially went to Korea (Santro was sold as a Kia product there) and then to other countries such as Algeria and Colombia. Soon, the number expanded rapidly to cross a hundred countries. Europe was on the list; so was North America, where Santro became the first Indian car to be exported (in Mexico).

By October 2004, HMIL had become the largest exporter of cars from India. Export success meant new challenges on the shop floor. As each country had different standards, the number of variants of Santro that were being produced (with left-hand drive, right-hand drive, automatic transmission, manual transmission, various Euro norms, engine specifications, etc) at its peak exceeded 500. “We had to put in place new processes to weed out any errors as so many variants were being rolled out of the same assembly line,” Sarangarajan points out. About 5.35 lakh units of Santro have been exported so far. The car’s success in the overseas market established India as a small car hub and HMIL has since exported over a million cars (all models, not just Santro).

The end of any journey can be difficult—and especially one that has led to such heights. Ask the employees at the Sriperumbudur manufacturing facility and their responses, while stoic, hint at well-deserved pride at having been a part of it.

“It was the first product of HMIL and we worked very hard to launch it in a record time of 17 months, right from the ground-breaking ceremony,” recalls SVN Prasad, who started in the product planning department in 1998 and is its senior general manager now. “We had to succeed and do so the very first time. There was no room for error,” adds K Asokan, who began in the quality department and is now the head of Plant 1. “Santro’s success gave us all the laurels and showed that Indian workers were as good as anywhere in the world,” points out CS Gopalakrishnan, head of Plant 2.

But this isn’t a desire to stay stuck in the past. They know that Santro, as a product, has become dated. However, they would like to see the brand continue. “After all, Santro is a household name in India today,” they say in one voice. Never say never but, for now, the car—and the brand—has rolled out of the manufacturing line for the last time and these three—along with their colleagues—were present to applaud it.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)