Intel Gets Another Shot At The Indian Consumer

Intel hasn’t been able to crack India’s rural market. Its new handheld device could now revolutionise banking in villages

In the later part of his career it was painful to see the ‘God of offside’, Sourav Ganguly, struggle to get the red cherry to the cover fence. Mostly bowlers didn’t bowl to his strength and sometimes his reflexes weren’t good enough. It was depressing to see an ageing champion try and fail to reclaim his legacy.

It is no different with Intel. The champion chip maker has tried to crack the Indian consumer market with a bunch of products — Community PC in 2006, Classmate PC in 2007, Bharat PC in 2009, Classmate in 2010 — and yet hasn’t been able to make any significant dent in it.

A lesser company might have packed in its hand. Not Intel. It is now ready with a new assault plan. It is trying something that Intel India President Praveen Vishakantaiah calls a “leap of faith”. It has developed a small handheld device, based on its bestselling Netbooks processor Atom, to target the rural banking market.

The device is as good as a computer in your hand; runs all standard software and integrates seamlessly with computers and servers that a bank or any other institution may have on its premises. Though Intel wouldn’t name the states where the pilots are currently being tested, sources say the device is being tested in Karnataka and Maharashtra.

The entire movement and the momentum of financial inclusion — the idea that financial services can be taken to the poorest — is what Intel is betting on. By next year, the finance ministry expects banks to reach all villages that have a population of 2,000. As per the 2001 Census, there are 100,000 such villages in India. A Wharton School study shows that the cost of a banking transaction drops from $1 at a bank branch to $0.10 if done through a business correspondent. Banks know this and they are experimenting with technology.

“We figured that rather than getting the villager to the bank, the bank should come to the villager,” says Sanat Rao, marketing director, embedded computing division, Intel India. His group worked with financial institutions, system integrators, application developers and end users to understand why access to credit is only the first step, why a suite of services is needed to liberate rural India from financial deprivation and why even small things matter, from the type of keys on the device to the killer apps. And the result is a product that’s a cross between an old Tetris game console and a credit card swipe machine.

In itself, this product may not affect the global balance sheet too much. “It won’t be a game changer for the $44 billion company,” says UBS Securities’ analyst, Uche Orji. “Even to make a 5-percent difference to its revenue, it needs to sell some 60 million units, which is unlikely, but it’d be a commendable proof of Intel’s diversification in India.”

It will also get Intel some part of the handheld computing devices market where it doesn’t have a huge presence. Desktop growth is sluggish at just 9 percent in 2011. Handhelds are estimated to grow 40-50 percent annually. Its rivals are branching out in handheld forms where it doesn’t have much presence as Atom has not gone very far beyond netbooks. Add to this the gap in the financial inclusion segment where existing technology options are not quite effective is getting Intel excited. Intel is working with financial institutions, independent software vendors, system integrators and users to crack this code.

Bundling banking with the sale of other services such as insurance policies, railway tickets, weather data and commodities prices is the way to financial inclusion, says Manish Khera, chief executive of Financial Information and Network Operations Ltd. (FINO), which, with 25 million customers, claims to have 90 percent of the market. (Intel Capital is an investor in FINO).

Today, there are fixed function devices only for financial transactions, for everything else mobile phones are used, says Khera. Moreover, these transactions don’t update the user account in real time. But the biggest limitation, says Khera, is that current devices work in a proprietary environment; an application that runs on one device may not run on another. That adds to the cost, which for a mere banking device is about Rs. 20,000.

At least four Indian product engineering companies are developing such products for their North American clients. There are others elsewhere developing such a device, but nobody has it ready yet, says Gartner’s principal research analyst Ganesh Ramamoorthy. He believes right pricing, maybe in the range of Rs. 10,000-Rs.12,000, will be critical for the success of this device. “I can see insurance and distribution companies taking to it in a big way, but it has to be affordable,” he cautions, alluding to Intel’s various PC programs that haven’t quite cracked the rural market due to price sensitivity.

“We don’t know what the pricing will be even though we are assembling it in our factory,” says K.R. Naik, chief executive of SmartLink Network Systems, Intel’s distribution partner in India. While the device is being manufactured by Sotac in Taiwan, he’s optimistic because this is one of the devices being validated by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI).

Vishakantaiah thinks Intel’s device could debut at about Rs. 18,000. But, practically speaking, that’s a call only manufacturers can take and they aren’t taking any now.

To achieve this level of pricing, Intel has developed the product slightly differently. The modular design of the product, where users can strip down features depending on the use, makes it amenable to many applications. For instance, Intel has closely worked with KTwo Technology Solutions to build a portable pathology lab that uses run-of-the-mill microscope, camera and algorithms for remote and on-site diagnoses. The device is being tested in rural health centres in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. KTwo founder chairman and chief executive, Anant Koppar, gives a thumbs-up to the supporting software availability for Atom and the interoperability among servers, PCs and handhelds as the key for choosing Intel.

In Hyderabad, Analogics Tech India uses its own software and user interface for delivering e-governance services in Rajasthan. Electronic design and engineering services company ProcSys has used this motherboard to build its own device which is now being tested as an electronic menu with additional services in restaurants. With KLG Systel, Intel has developed an energy management solution for the power infrastructure network and with Infosys a home management gateway that equipment manufacturers and service providers can use as a plug-and-play system to manage a variety of devices at home.

Intel has made the processor more rugged to make it industrial grade so that it withstands tough outdoor conditions. It has even enhanced the life-cycle, which for an average Intel processor is 18-24 months but is seven years for this Atom series. What this means is that a device maker using this processor will continue to order chips and receive support even as other notebook processors will keep disappearing every two years.

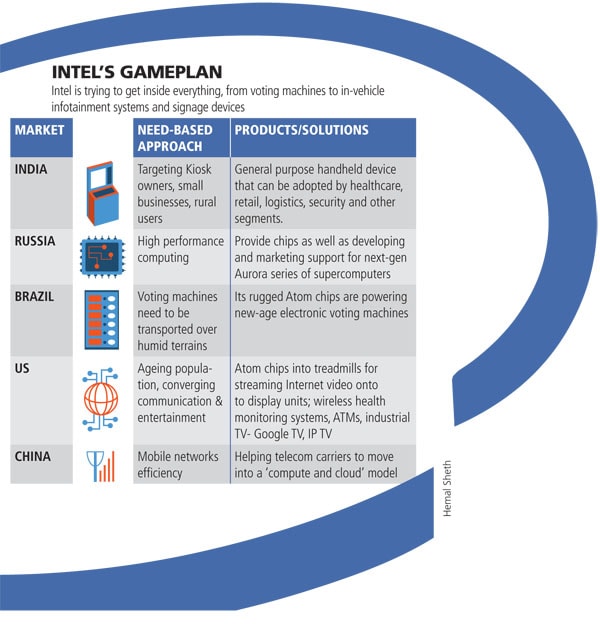

Intel is trying out various such initiatives in different markets (see graphic). “But in this case you see it effectively moving downstream, an innovation it has not done before,” says Orji of UBS.

Such innovations are critical for Intel as the Atom processor is still high horse-power and that’s often not what the market needs if you look at specific users, says Ramamoorthy. To that extent, even operating systems are being made leaner to cut cost and power. In July, Microsoft licensed ARM architecture which is widely used in portable devices.

The key in towing the handheld line in India is that Intel has learned from its earlier programs, both in terms of technology as well as partnership. The Community PC was based on shared computing in rustic conditions, even drawing power from car batteries, didn’t quite fly as the kiosk owners on whom Intel was counting, didn’t find anything inherently appealing and failed to build businesses around it.

But there was learning for Intel. “The Nettops that we have now launched take a regular power adapter to provide two-hours back-up at a $10 cost. We do apply the learning,” says Vishkantaiah. “Innovation takes time. iPod took six to seven years, that too for a US company with full control.”

Intel has chosen a good market for this proof-of-concept; finance and banking are not only evolved in India but also more open to such technologies compared to other countries. If proven here, it could even go to China, let alone Brazil, Russia and Africa, says Ramamoorthy. “In all fairness, they have 0.75 probability of succeeding,” he says.

Vishakantaiah says, “Innovation requires that one takes calculated risks. As an industry, if we aren’t prepared to take such risks, we will never advance and innovation will cease.” But what remains high on everybody’s watch list is whether this innovation bumbler will turn into an industry benchmark.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)