Jet Airways: In a Tailspin

Naresh Goyal's 21-year-old airline has been struggling. Its alliance with Etihad has done little good to either perception or reality. And the promoter seems to no longer hold sway over its navigation. It is a tough time to be Goyal

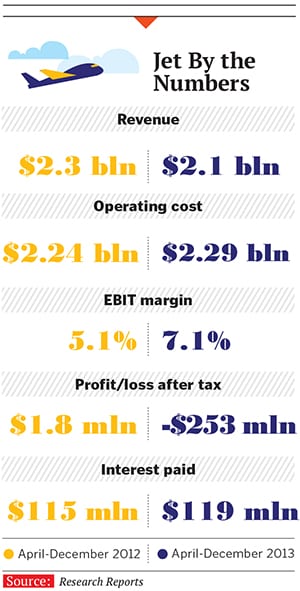

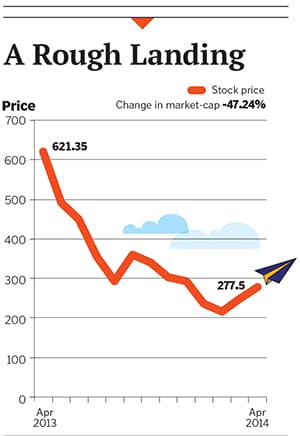

Over the last year, Naresh Goyal, known for his “ruthless passion” for his airline, has had to let go. Of a lot. Selling 24 percent of Jet Airways’ equity as well as a majority stake in its frequent flier programme which houses data about premium passengers. Selling slots at London’s Heathrow airport to Etihad Airways. Easing out his best friends Ali Ghandour and Vic Dungca from the board—both are airline industry men of global repute who had been by his side almost from the day he started Jet Airways. Sidelining or firing key staffers, including his wife Neeta, who had helped him steer the company through financial, regulatory and legal minefields—financial compulsions of the past few years made this move imperative. But these painful changes, made with the intent of staging even a semblance of recovery, have not restored Jet’s fortunes in any significant way. Financial year 2014 was in many ways the lowest point for what was once India’s most powerful service brand. Loss for the year is expected to be around Rs 2,000 crore. Till Q3, revenue fell 10 percent over the previous year and losses stood at Rs 1,514 crore. In its latest available results (Q3FY14), Jet recorded a (standalone) loss after tax of Rs 267crore, of which Rs 259 crore was from its domestic operations. Add the woes of subsidiary company Jet Lite (formerly Sahara Airlines), and the problem gets compounded. Jet Lite has negative net worth, and continues to make losses despite loans (Rs 180 crore till December 2013) from its stressed parent.

These numbers are chilling, but it isn’t yet time to pen an epitaph. However, there is certainly a cautionary tale to be told, deconstructing the tailspin that the 21-year-old airline finds itself in.

THE BELEAGUERED RANK & FILE

Goyal has typically administered Jet Airways closely. Albeit away from the notorious traffic jams around his airline’s corporate headquarters at Andheri east in Mumbai. For close to two decades, he worked from his home office in London. More recently, it is from his new base in Dubai, where he bought a posh 18,000 sq ft penthouse overlooking the Marina.

Senior managers of Jet, particularly in the operations and finance functions, have a bag packed and are ready for travel on most days. They are used to the chairman’s summons, and make quick trips to discuss one issue or another. Some of the trips are to Abu Dhabi, where Jet’s new strategic investor Etihad Airways is based. But more often, they meet Goyal in Dubai. The discussions centre on getting the airline back on the rails and tackling the airline’s biggest problem—its costs.

For the Jet executives, there is a sense of hopelessness about these meetings with the chairman. Attempts to cut costs have been ongoing, for as long as they can remember, yet the airline is in its poorest financial and operational shape. Many staffers, especially pilots, say they now keep close track of their bank accounts, making sure that salaries and allowances are being credited in time. And so far, they are.

Shifting Sands

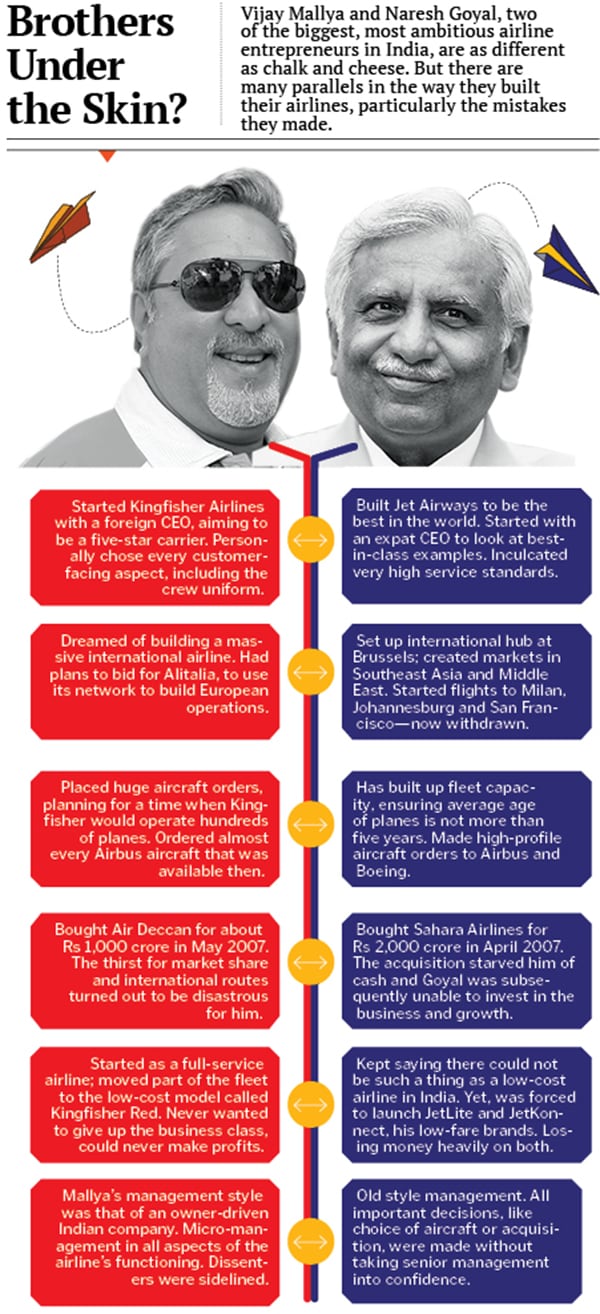

Though not many saw it then, India’s two largest network carriers, Jet Airways and Kingfisher Airlines, began a race to the bottom from 2007-08 onwards. Back then, hubris ruled. Competing intensely with each other, both Goyal and Vijay Mallya moved fast with their plans to expand their domestic and international footprint. Mallya’s Kingfisher Airlines, the newer of the two, had no profits and a higher cash-burn. It reached the bottom first but, two years on, Jet Airways is not very far behind.

For this story, Forbes India spoke to airline industry professionals from across the world. Goyal did not agree to an interview, nor did he respond to questions. We did speak to two of his former CEOs, one former COO and senior managers present and past.

First, a little background. The decline of Goyal’s fortune has been long drawn. It started in 2008 after low-cost carriers (LCCs) took root in India. By 2012, the crisis had peaked and Goyal could see his airline gasping for capital. Bankers, already stuck with NPAs from the notoriously value-destroying industry, refused to lend any more. The State Bank of India, for instance, is stuck with huge exposures to both Jet and Kingfisher. Sources in infrastructure finance company IDFC recall turning the screws on the Jet management and forcing an agreement to repay Rs 1 crore a day. IDFC has since recovered its loan.

For Goyal, there was no respite as costs continued to go up because of the depreciating rupee and high fuel prices. Sources in Jet’s senior management say Goyal had tried almost every ploy to control costs. He chopped loss-making routes, leased out his planes and cut out business class seats from most flights. For frequent fliers on international routes, food and service quality took a beating. In belt-tightening mode, Goyal ordered more seats added to the economy class: Boeing 777 airplanes, which had 274 seats in the back, now have 308. Additional rows meant passengers were packed tighter, leg room was minimal. Very often there was no place for hand-baggage in the overhead bins. (Pilots say flights are still held up when bags don’t fit and have to be sent down to the cargo-hold after passengers have boarded.)

But nothing seemed to work. A financial snapshot for the year ending March 2012 shows that the company’s interest outgo (consolidated) was twice its operating profit that year. Net worth was down to Rs 130.9 crore (wiped out in the following year). By the time the UPA government gave the green signal for foreign direct investment by foreign airlines, Goyal badly needed a bailout—an investor who would see him through the cash-burn in the long term.

Enter Etihad chairman Sheikh Hamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, one of the Emirates’ most influential money managers. As managing director of Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, he heads the world’s second largest sovereign wealth fund with assets of about $750 billion. Goyal wanted a deal that he was comfortable with. This meant good valuation and retaining enough equity. Gulf Air (which used to be partly owned by the sheikhs of Abu Dhabi, but has now been taken over by the government of Bahrain) was an investor in Jet Airways, and Goyal has always been in touch with the senior management. Not many know that Jet had given Etihad technical support when the airline was in its startup phase in 2003. The Abu Dhabi national carrier began to take shape from 2011, when it started declaring profits and, later, picking up minority stakes in a string of airlines around the world. With access to the sheikh’s pockets, Aussie expat James Hogan, former CEO of Gulf Air, and his team steered Etihad in its audacious attempts at global dominance.

After some haggling over Jet’s valuation, Goyal was able to convince Hogan that an equity alliance with his airline was the best way to tap the growing Indian traffic. Etihad finally valued Jet at $1.2 billion and the transaction closed in November last year. Jet received $380 million (Rs 2,060 crore) from Etihad for a 24 percent stake, and $150 million for half of the company that houses its frequent flier programme. There is the promise of far more—cheaper debt, more revenue from code-sharing and cost saving from joint purchases and other synergies.

But here’s the rub. For all the heat that the deal has generated, it may not be enough to save Jet. Most of the money that came in was used to retire some of the overdue debt. Yet, Jet’s debt still stands at $1.6 billion.

Apart from the financial re-engineering which is in progress, Goyal has been unable to address most of the structural problems with his airline. And his time may be running out. Two new and more focussed airlines, Tata-SIA Airline and AirAsia India, backed by the Tata group, are lining up on the runways. Some would say that Goyal, who blocked Ratan Tata’s grand plans to build an aviation empire (airline, airport and maintenance), is facing his karmic comeuppance. The battle to follow is likely to be brutal. With the advantage of pedigree and deep pockets, Tata-SIA Airlines is drawing up a blueprint for a full-service network airline. At the opposite end of the market, AirAsia India is set to rock the LCC segment, promising “truly low fares”.

Future Tense

Bharat Bhise, president and CEO of New York-based Bravia Capital Partners, a global investor in the transportation industry, has built and run many successful companies in the aviation sector in the US and more recently in China. He says: “Etihad’s focus is entirely on the India-Abu Dhabi sectors and picking up connecting passengers for their network. They probably wouldn’t care if Jet is profitable [on a P&L basis] as long as they don’t have to fund ongoing cash losses. Their investment [in Jet] will be well worth it if they can increase revenue by a billion dollars over, say, 10 years.”

Closer home, Kapil Kaul, CEO (south Asia) for CAPA (Centre for Aviation), says Etihad’s investment is surely not about turning around Jet Airways. “In all likelihood, the airline will continue to make losses on domestic routes, albeit to a smaller extent,’’ he says. In a research report on new partnership models in the airline industry, CAPA describes Etihad’s model as an “Egocentric Radial” alliance. Egocentric because it is driven by the individual airlines for strategic reasons. Radial because one airline is at the hub of the traffic, being fed by a number of other carriers represented as tubes carrying passengers to the hub. By this description, Jet Airways is on course to become Etihad’s widest tube.

Already, daily Jet Airways flights feed Abu Dhabi from Bangalore, Delhi, Kochi, Hyderabad and Chennai. From Mumbai, there are 11 flights a week. This will expand to more cities.

Real Problems

But can all the blame for Jet’s decline lie at its promoter’s door? Saroj Datta, an old Jet hand and its former executive director, says the chairman has always done things his own way. The regulatory environment and taxes are not conducive to the business but, for all its expat senior management, Jet has been run like a family affair.

Goyal, a man of the 1980s and ’90s, built his airline as a full-service carrier and has been unable to deal with rapid changes in the industry. Of its 562 flights, about 300 are operated by Jet Konnect on domestic routes. Every quarter, results show that it has been out-gunned by IndiGo and SpiceJet on these routes.

The ‘hybrid’ model, where it operates on multiple approaches, is clearly not working for Jet. It has two brands: JetKonnect for low cost and Jet Airways for two-class full-service.

Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman and managing director of infrastructure advisory firm Feedback Infrastructure, used to be on the top of Jet’s frequent flier list, earning and burning Jet Privilege miles for many years. A year ago, he (and Feedback) switched to IndiGo. “Flying business class on Jet was not the same experience anymore. The airline has withdrawn many privileges and is no match for IndiGo on punctuality and cleanliness,” he says. IndiGo has been slowly but surely taking away a lot of corporate customers like Chatterjee, who form the bulk of the frequent fliers.

Peter Luethi was COO at Jet Airways from 2003 to 2006, when he helped start and establish the airline’s expansion into Southeast Asia and the Gulf. Luethi, who now runs an airline consultancy in the US, says it is difficult for one entity to operate both a full-service and an LCC airline. “To make it work, the organisation structure will have to change. The two must be standalone, independently managed entities. This would require constant control and accountability.’’ he says.

A Jet senior vice president said on condition of anonymity that the airline has few options—it will continue to be a hybrid airline. “The business class market in India is underserved and we are best suited to support it,” he says, adding that he believes the airline will eventually be able to emerge from the current situation.

“Jet needs highly qualified, visionary management leadership to change its situation,” says author and Ohio State University’s Professor Nawal Taneja. The management has to be change-oriented. Continuing to do the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different outcome is insanity, he says. The Etihad management has the depth and systems that could help Jet turn around, he points out.

The new Indian skies

But though Hogan and his team are looking at integrating the airline into their network, it is clear that revival will be the Jet management’s job. Etihad is pushing to bring in change and professionalism. Yet Goyal and Hogan have been unable to appoint a CEO who can take on the challenge of dealing with the integration and the very competitive Indian environment.

Hogan’s first suggestion, Gary Toomey, a former Air New Zealand head, left unexpectedly within six months after taking over. Acting CEO Ravishankar Gopalakrishnan has also quit. The new name doing the rounds is that of Cramer Ball, former CEO of Air Seychelles. Ball, who went to Air Seychelles from Etihad on deputation, was able to bring the tiny airline back to profitability. But analysts in India are sceptical of these choices and say Jet needs an experienced hand.

There are indeed several contradictions between what is good for Jet and what Etihad wants. Jet had built up a good market presence in Southeast Asia and on the long haul to London and beyond into the United States. The conflict: Whether to feed its own network or funnel traffic into the Etihad network.

While no one can tell what shape Jet will take in a few years, Datta points out that Etihad’s entry marks the unravelling of Jet as a purely Indian carrier. “Its objectives, ethos and motives are no longer purely Indian,” he says. This is not in a nationalistic sense but in the way that British Airways is a British carrier or Singapore Airlines is Singaporean. The focus will change to funnelling traffic rather than generating traffic from India, he says.

From India to Abu Dhabi

As the relationship deepens, the two airlines may have a lot more code-shared flights. Already Jet aircraft are being leased to Etihad; some airplanes from the Mid-Eastern carrier’s huge aircraft order are likely to be for its equity partners. Pilots too are being shared/transferred. “Etihad is training Jet captains for conversion from smaller 737s to 777s,” says a senior check-pilot from Jet. “We are being offered one-year contracts after the six-month training. The good part is we have the option of returning to Jet Airways if we don’t like it there,” she says.

Feedback’s Chatterjee says he is willing to take a contrarian bet on a strong bounce back by Jet Airways in the future. “There is huge growth potential in the tier 2 and 3 cities in India. The government is working on improving the airport network. Jet knows this market well and should be able to tap it better now that its cash situation has improved,” he says.

Stock analysts who follow the Indian airline sector (and, significantly, many have stopped coverage of Jet), do not seem to agree with Chatterjee’s prognosis. Most are underweight on Jet Airways. In its April 2013 report on the airline, JP Morgan analyst Aditya Makhija says he expects competition to increase greatly with liberalisation in the business. He estimates a loss of Rs 1,339 crore in FY15.

For Goyal, the axis of power has shifted decisively. For all his hands-on management, Jet’s navigation is no longer in his hands in Dubai. Geographically, it has moved just 150 km south to Abu Dhabi where the sheikhs have their offices. Whether this shift in control will work for Jet is to be seen, but it is unlikely to go down well with its micro-managing promoter, eager to be seen as the man who rescued his own airline.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)