Nestlé 2.0: Back to basics with a new strategy

The Indian arm of the Swiss food giant is emerging out of the Maggi crisis wiser and clearer about its future direction, both in terms of business strategy and operational approach, under its new chief Suresh Narayanan

Jaskaran Singh, 28, a dairy farmer from Chaukiman village in Punjab’s Ludhiana district, refuses to believe there are any quality or safety issues with Maggi, the brand of instant noodles sold by 81 billion-euro Swiss packaged foods conglomerate Nestlé SA in India since 1982. Singh’s conviction stems from first-hand knowledge of Nestlé’s procurement standards—which he describes as stringent—rather than his love for the snack Indians have long-consumed to satiate hunger pangs at the oddest of hours.

The rural entrepreneur has been associated with Nestlé, the world’s biggest food company, for the past 11 years. He began as the operator of a captive collection centre for Nestlé’s dairy business, where milk from neighbouring cow farms would be agglomerated, processed mechanically and supplied to the company’s factory in Moga, 40 km from Singh’s village. At present, Singh has his own farm with 130 cows, supplying 1,200 litres of milk to Nestlé every day.

“If, by accident, any trace of antibiotics (sometimes used to treat cow infections) appear in the milk that Nestlé tests after collecting from us, the entire batch is rejected and our produce is subjected to rigorous testing the next day,” Singh says. The milk that Nestlé procures from farmers like Singh is used for the various dairy products it makes, including dairy whitener, ghee, curd, and child nutrition products such as Lactogen and Cerelac.

Singh’s conviction, however, wasn’t shared by the country’s food regulators, including the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), which found quality issues with Maggi that first led to its ban in several states last year, followed by a voluntary withdrawal of stocks from shelves across the country by the company.

However, it is the relationships Nestlé has fostered with people like Singh, and other suppliers, distributors, retailers and customers over the years that have helped Maggi re-enter Indian households after the Bombay High Court cleared the deck by setting aside the ban on August 13, 2015. In just five months after its relaunch, Maggi was once again the market leader in the Rs 2,000-crore instant noodles market, with a market share of over 50 percent in February 2016, according to data from market research firm Nielsen.

Nestlé SA’s global CEO Paul Bulcke had said on April 14, 2016, while announcing the company’s first quarter (January-March) earnings, that the Indian business, including Maggi, was recovering faster than expected. While the tide may have turned, the battle is only half-won, and Nestlé India’s Chairman and Managing Director Suresh Narayanan, 56, who took on the role in August last year, is taking nothing for granted.

Challenges persist

Though Maggi is the market leader again, its current market share is far below the 77 percent it enjoyed prior to the ban. Competitors like ITC’s Sunfeast YiPPee! noodles (the second largest selling brand of noodles with a 33 percent market share) have strengthened their position in Maggi’s absence, and new entrants like Patanjali Atta Noodles, from yoga guru Baba Ramdev’s consumer goods company Patanjali Ayurved Ltd, have intensified the turf war.

“One of the foremost priorities is to get the business and portfolio of Maggi into a much stronger position than at present. It will hopefully get back to where it was,” Narayanan told Forbes India during an interview in March. “We were out of the market for almost five months and the market has become a lot more competitive in that time.”

Narayanan says that he considers all peers, including ITC, Patanjali, Hindustan Unilever, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare and Nissin (makers of Top Ramen) credible competition with unique product offerings. “Competition energises me, it doesn’t intimidate me,” Narayanan says. “Each of us has our own core value propositions that we offer to customers and we have to ensure we work overtime to enhance these propositions.”

While Maggi’s masala and chicken variants have been available to consumers through retail stores and ecommerce platforms since the relaunch, it announced the return of other successful variants (four in all) like vegetable noodles and atta noodles in the third week of April. The legal overhang on Maggi’s presence on retail shelves is far from removed as the FSSAI has appealed against the Bombay High Court’s verdict in the Supreme Court (which was yet to take a final call on the matter at the time of writing this article). But as it stands, Maggi has cleared all the safety tests that the apex court asked for and which were conducted at the Central Food Technological Research Institute.

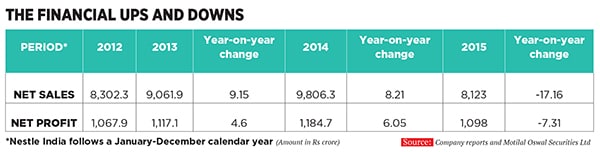

There is also the task of nursing Nestlé India back to financial health. On a year-on-year basis, Nestlé India’s net profit for the financial year ended December 31, 2015, halved to Rs 563 crore. This was largely due to an exceptional charge of Rs 501 crore recognised by the company on account of stocks of Maggi withdrawn from the trade channels; net sales during the same period declined by 17 percent to Rs 8,123 crore.

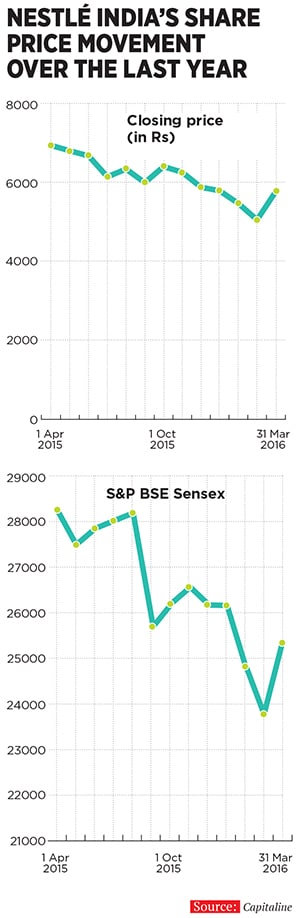

The Maggi imbroglio also took a toll on the company’s stock price. Around a year back (on April 1, 2015), Nestlé India was trading at Rs 6,938.35 per share on the BSE. A year later, its stock price had declined by almost 17 percent to Rs 5,768.95 per share (on March 31, 2016). Over the same period, the S&P BSE Sensex has fallen by 10.3 percent to 28,260.14 points.

While the fate of some of these issues is not in the company’s hands, Narayanan is utilising the crisis to bring about a fundamental shift in Nestlé’s operating strategy. The aim is to better prepare the company for future growth as well as any trials and tribulations it may face in the years to come.

Focus on volumes

The most crucial piece of Narayanan’s game plan involves steering Nestlé back towards a focussed strategy of growing volumes, away from the path of product rationalisation which the company had taken over the last few years. “What we sell are packets or cases, not rupees,” says Narayanan. “I always believe that market penetration and market share are driven by actual consumption of products, not just by increasing value through prices. It is all about going back to the basics of marketing as we learnt them.”

But cognisant of the fact that it may take a while for the entire portfolio of Maggi to be commercially restored, the company has turned its focus on innovating and launching new products in other categories, including milk and nutrition, coffee and beverages, chocolate and confectionery, and dairy.

And that is just as well. Because, while Nestlé has traditionally done well in categories like instant noodles and baby foods in India, it hasn’t been able to dominate certain other segments such as chocolates and dairy products, where competitors like Cadbury India (now known as Mondelez India Foods) and Amul (Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation) have taken pole position.

According to Nielsen data, the market for chocolates in India is worth Rs 7,276 crore, growing annually at 12.2 percent over the last three years. A November 2015 Euromonitor annual report says Mondelez had a 55 percent share of the market by value in 2014, while Nestlé was the second-largest player with a value share of 17 percent.

The company is aware that it can extend its presence in the chocolates market with popular brands like KitKat and Munch in its portfolio. Consequently, Nestlé recently launched variants like Kit Kat Duo and Munch Nuts. In the dairy products segment, it is launching its Greek Style Yogurt, a low-fat but creamy yogurt it sells internationally. “With rapid urbanisation, there is a clear opportunity to cater to an aspirational middle-class in India,” Narayanan says. “The mantra at Nestlé is to focus on getting back to double-digit growth—both in terms of topline and volumes.”

More launches in chocolates, dairy products and coffee are likely to be announced soon. “As a consequence of economic growth, there are many health issues with respect to obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular ailments that have surfaced. As a global company, we have a repertoire of 2,000 brands and Nestlé has the expertise to bring new product offerings, such as in the dairy segment, to address some of these concerns around well-being.”

Rama Bijapurkar, an independent management and market research consultant, says that while brand Maggi may have taken a hit, there was little to be concerned about in the long run, since such episodes were common with food companies (Cadbury India, Pepsi and Coca-Cola have all faced similar issues in India in the past). “Lots of brands take a lot of hits but they bounce back,” says Bijapurkar, who has served on the boards of several Indian companies.

“We like this change in strategy [to focus on volumes], as we believe disproportionate focus on margins/profitability had impacted Nestlé’s topline performance over 2012 to 2015,” says a Motilal Oswal research report.

In the 2012-13 and 2013-14 periods, Nestlé India’s revenues grew in single digits (9.1 percent and 8.2 percent respectively). For 2016, under Narayanan’s leadership, the Motilal Oswal report estimates the topline to grow by a significantly higher 18.3 percent.

This is down to the focus on growing volumes which, Bijapurkar says, is the right way to go. “The food revolution in India is yet to happen and there is enough of a market out there to justify growing volumes,” she says.

Even Harsh Mariwala, chairman of consumer goods company Marico, believes that is the approach that works: “I am of the opinion that growth comes first and profits come later. If there is sustained growth over a period of time, profits will follow.”

Which is why Nestlé India’s new chief is clear that while non-remunerative products will get culled, this process will go hand-in-hand with the addition of new products to the portfolio.

Must-win battles

Apart from that, in his third stint with Nestlé India (he was head of sales between 2005 and 2007, and executive vice president, sales, from 1999 to 2003), Narayanan has identified 10 must-win battles heading into the future. These include bringing back double-digit growth; restoring stability at Nestlé India; learning to manage volatility and adversity; revamping the company to become fast, focussed and flexible; making people fit for battle by enabling, empowering, engaging and energising; zero tolerance for non-compliance; nurturing key partners back to health; prioritising consumer service engagement, digital media engagement, media responsiveness, friendly face of Nestlé; focus on teamwork for speedier responses and a sense of ‘proud to be Nestlé’.

Winning some of these battles entails a distinct departure from how Nestlé India operated before the Maggi crisis. For instance, it is only post this problem that executives have been empowered at the level of the states to communicate with stakeholders such as local food regulators. To understand the importance of this move better, consider the genesis of the issue which took place in Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh. It was from a store here that Maggi samples were sourced for testing. Thereafter, in May 2015, the Department of Food Safety and Drug Administration of Uttar Pradesh in Lucknow published a report based on tests conducted at a referral laboratory in Kolkata. The results showed lead content in excess of the permissible limit and the presence of MSG (monosodium glutamate). While MSG in food products is permitted, the regulator had a grouse that Maggi packets carried the disclaimer, ‘No Added MSG’, in the past (before the investigations began).

Over the next few days, several other state governments got samples of Maggi tested to assess if they violated food safety standards and a number of them, including Punjab, Assam, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana, Uttarakhand, Jammu & Kashmir, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu banned the product.

Subsequently, even as Nestlé continued to defend its product, stating that it was fit for consumption, it voluntarily withdrew Maggi from the market, citing an “environment of confusion for the consumer” that existed at the time. “The issue could have been nipped in the bud if it was dealt with proactively on channels like social media for instance,” points out Mariwala.

“In the area of food quality and safety, different Indian states have different interpretations of what is right and wrong. It is not just one FSSAI that takes all decisions, there are other local regulators as well,” Narayanan observes. “As an organisation we have started putting greater emphasis on environment-sensing skills, to be able to interface professionally and regularly with key stakeholders in the states; and resolve issues as and when they come up rather than allowing them to fester and take on greater proportions.”

As a result of this strategy, Nestlé India is going to focus on acquiring more talent at the mid-management level. Narayanan calls this the “belly of the organisation where the action really happens”.

The company has already mandated one employee at each of its state offices with the sole responsibility of interfacing with the government and looking into any complaints that may surface with respect to Nestlé products proactively.

Greater external engagement

The other area of focus for Narayanan is greater external engagement. He concedes that Nestlé India hasn’t always been the most public of organisations when it comes to external communications, and that is something that he’d like to change. Not only does this entail greater interaction with the media, but also accelerated “shared-value” and corporate social responsibility programmes with stakeholders and more targeted engagement with consumers.

Nestlé faced criticism due to the perception that it hadn’t done enough by way of its initial response to the crisis. It took a while for the global headquarters at Vevey, Switzerland, to react to what was happening at its Indian subsidiary. It was in the first week of June 2015 that Bulcke flew down to India to allay concerns around Maggi. But the delay didn’t help Nestlé’s cause.

“If a consumer is in doubt, then the brand is out; and a period of even 10 days without proper communication in the life of a brand that is in crisis is a very long period,” says Jagdeep Kapoor, a brand expert and chairman and managing director of Samsika Marketing Consultants.

Nestlé has redeemed itself subsequently with a series of effective ad campaigns, which sought to evoke a sense of nostalgia and pull at the heart strings of Indian consumers. It even associated itself with Fauja Singh, a 104-year-old marathon runner, ahead of the annual Mumbai Marathon in 2016. The company tapped into digital media by publishing a series of short videos on its YouTube channel, where the protagonists ask longingly: “Kab wapas aayega yaar?” (When will you [Maggi] be back?) There were also Twitter hashtags like #WeMissYouMaggi that were actively promoted.

Even the central themes of Maggi’s television ad campaigns have changed. It is no longer only about a mother quickly whipping up a bowl of Maggi as a treat for her young child in “2-Minutes”. The characters of the new Maggi commercials include college students bonding with their seniors in hostel rooms over the snack. “What the target group for communication campaigns around Maggi was and what it is at present mirrors the evolution of young India,” Narayanan says.

Nestlé brought in McCann Worldgroup as the creative agency to execute the new campaign, relying on the expertise of ad veteran Prasoon Joshi. “Some water had flown under the bridge when Nestlé requested that we work alongside them and our first job was to seamlessly communicate through various channels,” Joshi, chairman of McCann Worldgroup, Asia Pacific, and CEO and chief creative officer at McCann Worldgroup, India, tells Forbes India.

“This was one of the toughest campaigns one has worked for,” Joshi says. “It was a charged atmosphere and sensitivity and surefootedness were the need of the hour. With the support of the Nestlé management team behind us, as the first step, we created the ‘100 years of Nestlé’ communication so that it was realised that this is not just another company; that there exists a history with our country and concrete commitment of a 100 years behind it. This was a revelation to many and resonated deeply with all the stakeholders.”

Further, the emotional leg of the campaign needed to manifest love for brand Maggi in absentia, Joshi says. McCann developed a creative plan keeping the consumer at the core. Without getting into regular product shots or brand eulogies, the campaign sought to give voice to the consumers’ longing for the brand experience.

Nestlé will need to sustain the velocity and intensity of these brand and marketing campaigns, Kapoor says, since the challenge is also about recovering market share from rivals. “The strategy going forward is being discussed, but consumer connect and brand love will of course be at the core,” Joshi says.

Building relationships

As mentioned earlier, relationships with partners such as suppliers, distributors and retailers are key to the success Nestlé has so far tasted in India (prior to the crisis), Narayanan says, and he is sensitive to the fact that these bonds need to be further fortified as the company recovers.

“It is not only our business that has suffered. We work with 400,000 wheat farmers, 15,000 spice farmers and 1,500 distributors who have also been impacted because of the crisis,” Narayanan says. “The collateral damage has been enormous, but neither of these partners nor our 7,400 employees have expressed lack of trust in us or left us. So we want to nurture them by giving them new business opportunities.”

While it may be too early to predict a sustained financial recovery for Nestlé India, the sequential earnings reported by the company have been encouraging. In the October-December 2015 quarter, Nestlé India posted a turnover of Rs 1,959.46 crore, up 12.5 percent quarter-on-quarter—net profit in the same period grew by 47.5 percent to Rs 183.19 crore. The profitability number also compares favourably to the Rs 64.40 crore-loss the company suffered in the June 2015 quarter.

“Our profit margins are up between Q3 (July-September) and Q4 (October-December), but compared to the levels in the previous year (2014) they are low,” Narayanan admits. “I see a sequential improvement taking place and if Maggi picks up traction and some of the new product initiatives take off, we should expect respectable running rate of growth in a couple of quarters.”

As the Motilal Oswal report puts it, “The Maggi crisis can eventually prove to be a blessing in disguise for Nestlé and help shake things up under the new MD, who we believe is pressing the right buttons.” At the same time, it adds: “Though we like his focus areas, we believe the task ahead for the new MD is herculean. Focus on volume growth, innovation and newfound vigour in the management are key positives. Nonetheless, it will be a while before the fruits of [the]new strategy are realised.”

The good news is that Nestle, and Narayanan, show all signs of willing to be patient.

With inputs from Shruti Venkatesh