Suzlon's rise from the ashes

The resurrection of what was once one of the world's largest wind turbine manufacturers has all the elements of a blockbuster, including a promoter determined to redeem himself, and a deep-pocketed knight in shining armour

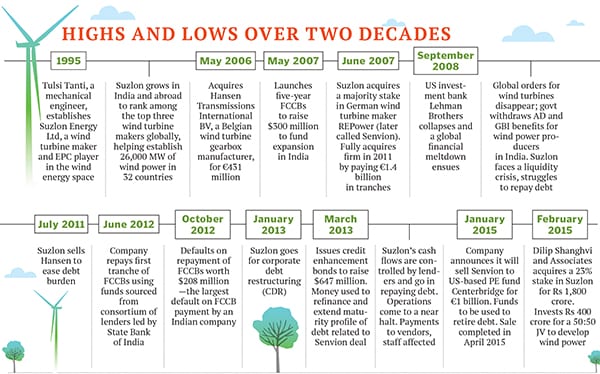

Earlier this year, Tulsi Tanti, the 57-year-old chairman and managing director of Suzlon Energy, moved into his renovated office at One Earth, the company’s headquarters in Pune. The redesigned office in a sprawling, ten-acre campus in the city’s Hadapsar area is better compliant with Vastu—the Hindu science of architecture that is supposed to channel positive natural energy to the benefit of those inhabiting the physical space. And Tanti’s stars do appear to be better aligned at present than they have been in the past. His company, which has been struggling with losses since FY2009, posted its first quarterly operating profit in three years in the April-June 2015 period.

Though battle-scarred, Suzlon’s chairman appears more relaxed now than he was a year ago when the company was overleveraged and operations were at a near standstill. Tanti has since been painstakingly trying to restore the credibility that he had lost with stakeholders like lenders and customers due to an infamous debt default that led to a restructuring of the company’s borrowings and hamstrung its ability to sustain business operations at the same scale as before. “The last 36 months have been the most turbulent times that we have experienced,” says Tanti, a mechanical engineer by education.

Suzlon, a manufacturer of wind turbines and an end-to-end turnkey engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) player in the wind energy space, holds the dubious distinction of being the largest defaulter on repayment of foreign currency convertible bonds (FCCBs) issued by any Indian company to date: In October 2012, it defaulted on the repayment of FCCBs worth $209 million, which were due for redemption.

This was on the back of operational challenges at home and abroad arising from the economic downturn that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, and a debt-funded international expansion strategy that didn’t go as per plan. Suzlon, which used to rank among the top three wind turbine makers in the world, saw its business shrink rapidly due to liquidity constraints.

It wasn’t alone in the adversities it faced during this period: Several Indian firms in the metal and mining sectors, especially those with significant exposure to international markets, burnt their fingers. But not everyone has been able to script a recovery like Suzlon has.

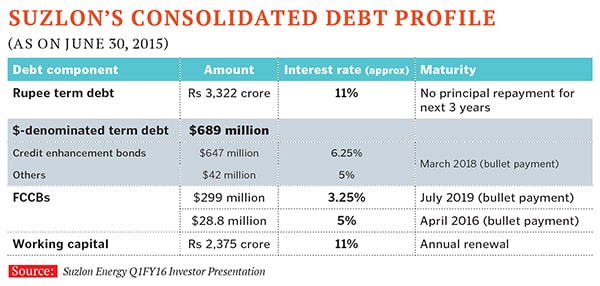

Its turnaround is a story of how lenders can work with their borrowers to help a company get back on its feet while ensuring they recover their dues; a story of how a well-meaning white knight with deep pockets can change the tide of fortune; and, most importantly, of how a promoter can redeem himself by setting his ego aside, putting the company’s interests before his own, and selling assets that may have been the crown jewels of his business. Suzlon was able to halve its debt from Rs 14,281 crore as of March 31, 2015, to a current Rs 7,010 crore. (This is excluding FCCBs that were restructured.)

The growth phase

Till 2007-08, Suzlon was a healthy company. In FY2008, it posted a consolidated net profit of Rs 1,017 crore on a turnover of Rs 13,679 crore. Over 20 years since Tanti founded it in 1995, the company has been supplying wind turbines to customers across 32 countries, in North and South America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. Through its wind turbines, it has helped establish a wind power generation capacity of 26,000 MW the world over. In doing so, Suzlon had positioned itself as a competitive global player in this space. In India specifically, government incentives to promote wind power generation, including accelerated depreciation (AD) on wind power assets and generation-based incentives (GBI), attracted various companies towards creating wind power capacity. This meant brisk business for Suzlon.

With the Indian business doing well, Suzlon made some big-ticket global acquisitions. In 2006, it acquired Belgian wind turbine gearbox manufacturing firm, Hansen Transmissions International NV, for around €431 million. In 2007, it bought a majority stake in the German wind turbine maker REPower (renamed Senvion in 2014). Between 2007 and 2011, Suzlon progressively ramped up its stake in Senvion and eventually bought out the whole company. Through several tranches, it paid around €1.4 billion to acquire Senvion. Most of this expenditure was funded through debt raised internationally.

Senvion gave Suzlon access to new and better technology, especially in the offshore wind energy space, and greater access to international markets. The German firm soon accounted for a majority of Suzlon’s consolidated turnover. In the nine-month period ending December 31, 2014, Senvion contributed as much as 73.5 percent to Suzlon’s consolidated revenues of Rs 14,928 crore. Also, while the standalone Indian business called Suzlon Wind reported a loss, Senvion’s operations helped the consolidated business report earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) of Rs 482 crore.

The downfall

But when the world economy took a turn for the worse in 2008, Suzlon got caught in a tailspin. A liquidity crunch in the global financial system meant that orders for wind turbines from international clients disappeared. In some instances, receivables from clients were delayed. The after-effect of the crisis was to last for a few years to come. “We were in a globalisation phase and the collapse of the financial market impacted our industry,” says Tanti.

To demonstrate the extent to which the global wind power sector stood beleaguered, Tanti notes that the top five wind turbine makers in the world, including Vestas and GE, posted a combined loss of €2.5 billion in the calendar year 2013, the highest level of losses witnessed by the industry in the last two decades. The situation could have been better for Suzlon had the Indian business continued to perform well. But that wasn’t to be. The AD and GBI benefits that were extended to wind power developers in India were suddenly withdrawn in 2012 and Indian firms didn’t have any further incentive to invest in this sector. As a result, wind turbine orders from India dried up.

When AD and GBI benefits were available to the wind power sector in India, capacity to the tune of 3,000 MW was being added per year. This fell dramatically to 1,500 MW after these incentives were withdrawn.

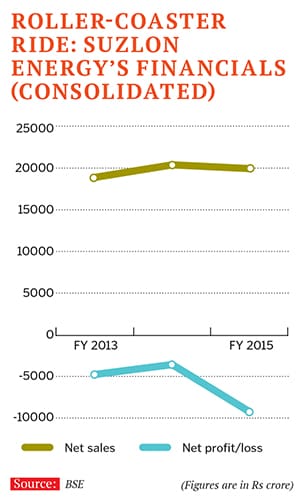

In the five years between FY2010 and FY2015, Suzlon’s losses widened nearly ten times to Rs 9,157.60 crore. Its turnover in the same period declined marginally by 3.7 percent, to Rs 19,954 crore.

The debt conundrum

Despite the challenges in the US and India, Senvion continued to do well in Europe. But the German company posed a unique problem for its Indian acquirer. Suzlon had borrowed money from the European market to finance the Senvion acquisition, but following the financial crisis, the company had to transfer the debt to India. In the process, its cost of borrowing went up, but Suzlon managed to service this debt till its Indian operations were generating enough cash. However, when the Indian market slumped, Suzlon’s ability to service debt suffered as well.

“The main constraint that we faced was in Germany,” Tanti says. “It wasn’t because it (Senvion) was a bad investment. But the banks there didn’t support our investment. Senvion was a debt-free company, but neither did they allow us to raise any debt on Senvion’s balance sheet nor were we allowed to repatriate the cash profits from the company to India, which could have then been used to service the debt related to the acquisition that we transferred. Senvion had a cash reserve of around €300 million, but this money couldn’t be utilised to pare the group’s debt.”

Meanwhile, in 2007, Suzlon also raised five-year FCCBs to the tune of $300 million to finance its expansion in India. As these FCCBs neared maturity, Suzlon managed to pay off a small tranche that fell due in June 2012 with money borrowed from its consortium of lenders, led by the State Bank of India (SBI). But the banks made it clear that Suzlon would have to fend for itself when it came to repaying the remaining FCCBs that were due for redemption in October 2012, says Supratim Sarkar, executive vice president at SBI Capital Markets, SBI’s investment banking arm that has been actively involved in restructuring Suzlon’s finances. Hectic negotiations between bondholders and the company failed to secure Suzlon a four-month extension for debt repayment that it sought and the company defaulted on the redemption of FCCBs worth $208 million.

The writing on the wall could not have been clearer: Suzlon could no longer service its debts and the company went for corporate debt restructuring (CDR) in January 2013.

CDR came with its own set of challenges for the company. “It was a classic conflict. Whatever cash flows the business generated went to the banks. If any money was left after that, it would go to my vendors and the remaining would be used to pay salaries,” Tanti says. “Over the last two years, most of my employees haven’t received their salaries on time. Under CDR, I don’t control the company’s cash; it is controlled by the banks.”

As a part of the restructuring, it was decided that the debt related to Senvion’s acquisition would be refinanced through a credit enhancement bond to be issued by Suzlon; this would be backed by a standby letter of credit from SBI. “It wasn’t an easy task at all, but JP Morgan joined hands with us and we could manage to successfully place the bonds,” Sarkar of SBI Capital Markets recalls. Consequently, Suzlon raised $647 million in March 2013.

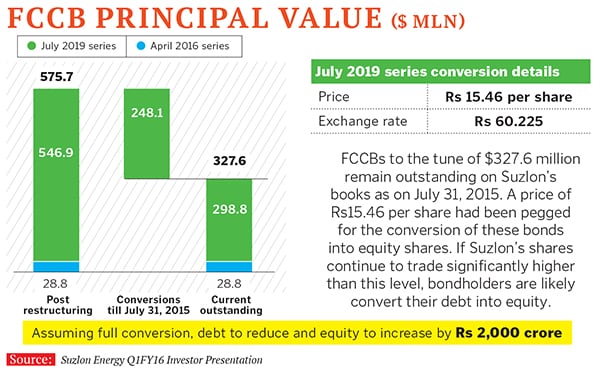

Simultaneously, it also worked with bondholders to restructure the FCCBs it had issued in May 2007. After the restructuring, which took place in May 2014, the principal value of Suzlon’s outstanding FCCBs stood at $575.7 million. Out of this, the company is liable to repay $28.8 million in April 2016 and the remaining in July 2019. The price for the conversion of these FCCBs into equity shares of the company was pegged at Rs 15.46 per share. Since Suzlon’s bondholders have a significant upside in converting their bonds into shares, with the company’s stock price consistently trading above the conversion price, around $248.1 million worth of FCCBs had been converted into equity shares of the company till July 31, 2015. As a result, FCCBs worth $327.6 million are now left to be repaid.

If Suzlon can maintain or improve its current share price (consider that it was trading at Rs 21.65 on September 10), Tanti expects the remaining FCCBs to be converted into shares as well, which would mean it may not have to shell out any extra cash to repay this component of its debt. Suzlon also allotted some shares to its Indian lenders who have since sold them in the retail market to recover a part of their dues.

Excluding the FCCBs that Suzlon had raised, the company had a debt of around Rs 14,281 crore as on March 31, 2015.

Selling the crown jewel

While lenders did their bit to restructure the company’s debt, another key clause in the CDR package was that Suzlon would have to monetise assets to generate the cash that was to be used to repay its debt. More specifically, lenders coaxed Tanti to sell Senvion lock, stock and barrel. Suzlon managed to do so in April this year for a consideration of around €1 billion. (The deal was announced in January 2015.) The German company was sold to US private equity firm Centerbridge and the entire proceeds from the sale were used to retire debt.

As a result, Suzlon has managed to halve its outstanding debt (excluding the FCCBs) to Rs 7,010 crore at the end of the June quarter. Most of Suzlon’s remaining debt is back-ended. The company doesn’t have any significant debt repayment obligation over the next two years, according to Tanti. “I have to only keep servicing the interest cost, which works out to Rs 800-900 crore per year and that can be easily done,” he says.

As a result of all the initiatives, Suzlon’s interest cost came down by as much as 36 percent quarter-on-quarter to Rs 293 crore in the April-June 2015 period.

By this time, the outlook for the wind power market in India had begun to change for the better as incentives like AD and GBI were back on the table. “He (Tanti) realised that he was constrained and wouldn’t be able to take advantage of the business opportunity that the Indian market presented unless the debt overhang on the company was removed,” says P Pradeep Kumar, managing director and group executive (corporate banking) at SBI. “It was at this time that he felt that he needed to sell the European subsidiary.”

Kumar says Tanti’s initial plan was to take Senvion public and dilute his stake in the company by around 30 percent. While this may have yielded Tanti a better valuation for his stake, it would have been a time-consuming process. Suzlon’s lenders convinced Tanti to sell Senvion at one go because “cash was king”, says Kumar.

Though the debt burden on Suzlon eased considerably, it still needed fresh funds to spur future business growth in order to prepare itself to start servicing the back-ended loans that will be due again in two years. Belonging to the same Gujarati business community, Tanti knew Dilip Shanghvi, managing director of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, socially. The two had common friends who approached Tanti to gauge his interest in an equity partnership proposal from Shanghvi, who was looking at new avenues to invest his personal wealth.

“I told them that I was willing to meet, but any transaction could only happen after selling Senvion as it made sense to bring in equity only after reducing the debt overhang,” says Tanti. “I needed the equity for business, not for debt repayment.”

With the divestment of Senvion on the cards, Tanti got talking with Shanghvi to understand why he wanted to invest in Suzlon. Two meetings later, the deal was finalised. In February 2015, Dilip Shanghvi and Associates (DSA)—the Sun Pharma MD’s personal investment vehicle—bought a 23 percent stake in Suzlon for Rs 1,800 crore.

This money, along with the cash of Rs 3,070 crore on Suzlon’s books as on June 30, 2015, and the fresh injection of funds that Tanti hopes to generate from operations, will be enough to take care of Suzlon’s growth aspirations for the next five years, he says. In an email interview with Forbes India, Shanghvi says he saw “great potential” in Suzlon’s business fundamentals due to its “world-class technology and R&D capabilities”.

“Now that the company (Senvion) has been sold off, Suzlon’s debt has become manageable. We believe Suzlon has the potential to become a global leader again,” says Shanghvi.

After the deal, and following the dilution of equity that happened on account of conversion of FCCBs into equity shares, the Tanti family held a 21.8 percent stake in Suzlon as on June 30, 2015, while Shanghvi and his associates held one percent less than that. Though Shanghvi’s stake in Suzlon is only marginally lower than that of Tanti’s, he is clear that his investment in the company is purely financial in nature and that the Tanti family continues to manage Suzlon. “But if the team needs my strategic inputs on any matter, I am happy to give,” says Shanghvi. He also categorically rules out any possibility of DSA raising its stake in Suzlon.

What also encouraged Tanti to accept Shanghvi’s proposal was what the latter told him during the course of their discussions preceding the deal. “Dilipbhai said that he wanted to invest in the company as he wants to see Indian promoters position themselves as global leaders in the international marketplace and he believed that Suzlon and I have the capability to achieve that,” Tanti says.

Tanti and Shanghvi’s association isn’t limited to the Rs 1,800 crore investment in Suzlon alone. Shanghvi has also invested Rs 400 crore in an equal joint venture (JV) created by the two entities that will develop wind power projects in India. DSA has also committed working capital loans to support the development of 1,200 MW of wind power generation capacity over a two-year period.

Back on the growth path

For the first quarter of FY2016, Suzlon posted a healthy net profit of Rs 1,079 crore. However, this net profit was largely the result of a one-time gain arising from an accounting treatment of foreign exchange translation due to the sale of Senvion. But what is encouraging is that the company reported an operating profit apart from this one-off item as well, its first in three years. Its revenues stood at Rs 1,542 crore in the June quarter this year, up 66 percent over the preceding quarter. The company’s Ebitda stood at Rs 146 crore during the same quarter, versus a loss of Rs 554 crore in the March quarter. This is the highest quarterly Ebitda reported by the company in the last three years. Significantly, Suzlon reported a profit before interest and tax (PBIT) of Rs 85 crore during the June quarter, its first in three years.

At the same time, Suzlon has accumulated losses of around Rs 4,000 crore, according to a Nomura Research report dated June 5, 2015. It needs to recoup and the company may well do so if it can sustain the momentum it has displayed in the first quarter of the current fiscal.

Tanti is confident that as business picks up, Suzlon will turn in a net profit for the entire year. If it succeeds in doing so, the company would have reported an annual net profit for the first time in six years. Suzlon aims to get there through a recalibrated approach to international expansion as well as by growing its existing and new lines of businesses in India.

Tanti says his ambition is to help Suzlon regain the 50 percent global market share that it once enjoyed. In FY2015, Suzlon had a market share of 25 percent, Tanti says. “This year (FY2016), we are targeting a 35 percent market share and want to take it up to 45 percent next year,” he adds.

Though Suzlon has been operational in 32 countries in the past, it only wants to focus on four international markets—India, China, North America (US, Mexico and Canada) and Latin America (Brazil, Argentina and Chile). These four regions, according to Tanti, represent 70 percent of the global wind energy market.

“Merely catering to the 3,000 MW market in India won’t be enough to justify the $50 million per year-investment that Suzlon will be putting in upgrading its technology each year. We need to be present in other markets as well to make this investment viable,” Tanti says.

At the same time, Suzlon is willing to forego smaller markets like South Africa and Australia where it was the market leader earlier, but which aren’t as lucrative as the four regions it is currently focusing on.

The other vital part of Suzlon’s future growth strategy is its renewed focus on the India business. For instance, the JV formed between DSA and Suzlon is in a new line of business for Suzlon. This as-yet-unnamed joint venture is a separate 50:50 partnership, where each partner will invest Rs 400 crore to develop wind power. The entity will develop around 450-500 MW of wind power assets across Indian states and sell them to interested buyers, mostly financial investors looking to get into India’s promising renewable energy space.

The Narendra Modi-led government at the Centre has pegged a target of developing 60,000 MW of wind power in India by 2022 and this augurs well for Suzlon, which is already seeing traction in the orders it executes. “We are focussed on growing volumes again. In the last full fiscal (FY2015), Suzlon supplied turbines for 450 MW of capacity. We have done 200 MW in the first quarter of the present fiscal alone,” Tanti says. He expects business to pick up in the second half of the fiscal, which is traditionally the period in which volumes increase as projects near commissioning.

Another potential game-changer for Suzlon’s Indian business is the National Offshore Wind Energy Policy, which was approved by the government on September 9. Though Suzlon has sold Senvion, it was able to facilitate a technology transfer that gives it precious know-how in manufacturing wind turbines that can be installed over water bodies. The company is conducting a feasibility study in Gujarat; the first pilot project will be for 600 MW.

Though Tanti refrains from providing any direct guidance, he indicates that India is expected to add around 3,000 MW of wind power capacity in 2015-16 and Suzlon will target a 35 percent market share, implying a business of 1,050 MW. This is significant as Tanti says that at this level of production, Suzlon can break even, and with a subsequent ramp-up in volumes, the company will generate additional cash.

The other line of business that Suzlon is exploring is the development of hybrid power projects that combine solar and wind energy. This can lead to the creation of a power project that generates electricity round-the-clock and at a higher plant load factor, which is what investors want, Tanti says.

Suzlon plans to offer turnkey solutions to its clients by buying solar power installations from the open market through a bidding process and combining it with wind power equipment that will come from one of its 11 factories in India. It also plans to spend Rs 200 crore in developing three production facilities in Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Suzlon is also bullish on its services division that looks after the maintenance of wind farms across the world. “This is an annuity business and has grown to become 15 percent of our topline,” Tanti says. While Suzlon’s wind turbines business yields an operating profit margin of 12-15 percent, the services vertical operates at a 20 percent margin.

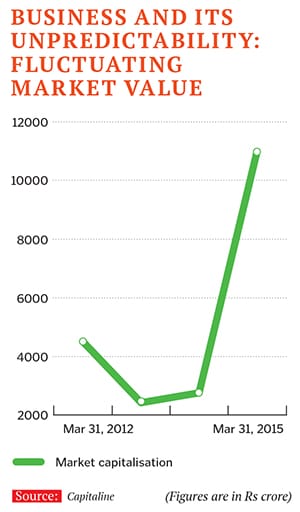

Analysts tracking the sector are pleasantly surprised by the turnaround that Suzlon has exhibited so far and believe that the company can bounce back stronger over the next couple of years. This confidence has even begun reflecting in the market value of the firm. Its market capitalisation has risen nearly five times from Rs 2,761.85 crore (as on March 31, 2014) to Rs 10,981.10 crore as on March 31, 2015. The benchmark 30-share Sensex gained around 25 percent in the same period (see chart.)

“Suzlon has been an established player in the wind turbine market having supplied more than 40 percent of India’s 23 GW (1 GW is equal to 1,000 MW) of installed wind (power) capacity. With wind power gaining ground, the market is likely to expand to 3-4 GW per annum over the next two to three years, portending humongous opportunities,” says a June 12, 2015, report by Edelweiss Securities, which notes that the company has a healthy current order book of 1,300 MW.

Putting the company first

The sale of Senvion and Shanghvi’s investment helped bring Suzlon back from the edge of the precipice, but lenders and merchant bankers who have worked with the company say all this may not have been possible had Tanti not put the company’s interest before his own. “What they (Suzlon) have done well is to work passionately on the suggestions we put forth to them—be it to enhance their management bandwidth or sell crown jewels like Senvion— and showed determination in implementing these changes,” SBI’s chairman Arundhati Bhattacharya tells Forbes India. “At the end of the day, he (Tanti) really and truly wanted to see his company do well.”

SBI’s Sarkar says he met Tanti every month or every alternate month over the last six years, working with him to turn Suzlon around. “One good thing about Tulsi Tanti is that, unlike other promoters, he wanted his company to survive and turn around more than maintaining his own stake in the firm,” says Sarkar. “Where others may have been cowed down by the kind of adversity that Suzlon had faced, Tanti tackled the situation head on, without blinking or pausing to think what would happen to his personal wealth in the process.”

Though Tanti is happy with his company’s present state of affairs, he hasn’t forgotten the personal tribulations he has faced in the past. “We have ensured that none of our stakeholders suffer a financial loss, be they vendors, customers, employees or lenders. There may have been delays in payment, but no loss. The only loser has been the promoter whose shareholding in the company has fallen from 60 percent to around 20 percent,” says Tanti.

He has had to reach out to many people to seek help. “When we went to some people to request their help personally, we had to listen to some unpleasant things. They were apprehensive about whether they would get back their money or not.”

Over the last six years, Suzlon was caught in the eye of a storm that appears to have blown over. After a long hiatus, the winds are finally blowing in the right direction at One Earth.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)