Why Arvind Rao and OnMobile Went Down a Dark Road

He had impeccable credentials. And his company, OnMobile, was India’s most successful mobile VAS company. Then he did something stupid

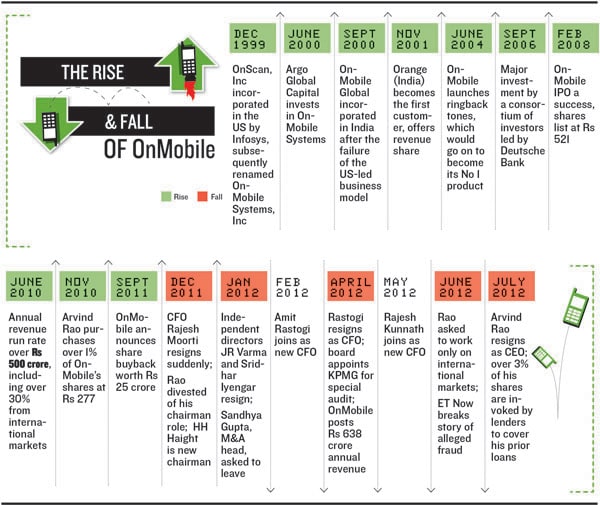

On November 23, 2010, Arvind Rao, the 53-year-old co-founder and CEO of OnMobile, bought approximately 6 lakh shares of his company from the open market, representing a little over 1 percent of the company’s total shares. Rao already owned over 10 percent of the company’s shares.

At Rs 277 a share, he had to pony up nearly Rs 16.5 crore to acquire them.

He still did it because he felt OnMobile, his baby, was severely undervalued. Since its blockbuster IPO in early 2008, OnMobile shares had climbed to over Rs 700 before falling.

Rao felt it was just an aberration—the market hadn’t realised the value of his baby. The world was at the cusp of the mobile revolution; billions of people around the world had yet to experience phone services beyond voice; and OnMobile was just getting started on its international journey.

Incubated within Infosys in 2000, OnMobile had arguably the best pedigree in the Indian business world. In the parochial world of Indian mobile telephony, its customer list covered almost every operator, attesting to the value of its services. With over 100 million subscribers for its services, including for the once wildly popular ringback tune, it had grown rapidly from just over Rs 2 crore in income in 2002 to over Rs 500 crore by 2010. At 20-plus percent, its profit margins were a source of envy and puzzlement to many, given the razor thin margins prevalent in the mobile value-added services (VAS) industry. Under Rao, OnMobile had gone international, generating nearly a third of its revenue from over 50 other countries.

So he went ahead and borrowed money to buy the shares, thinking nothing of the interest it entailed or the fact that he’d need to put up nearly half his existing shareholding as collateral.

That would turn out to be the worst decision he ever made.

OnMobile’s shares continued to fall from those levels, while Rao’s interest payments ballooned.

Consumed by the downward spiral of his baby and his worsening personal debt situation, his characteristic energy and enthusiasm waned, visible to most of his senior colleagues.

In an attempt to provide a floor to OnMobile’s share price, Rao managed to push through a controversial share buyback plan totalling Rs 25 crore last year, despite serious reservations from other board members.

Motivated by OnMobile’s growth all these years, he had never paid much attention to his salary, most of which went towards the monthly rental on his sea-facing apartment in Mumbai and his BMW 7-Series, both paid directly by the company.

He requested the board for a significant salary increase, arguing (rightly) that his Rs 1 crore salary was substantially below what the market would pay the CEO of a Rs 600-plus crore international company. But they would have none of it.

After that, he requested a personal loan, which too they denied.

Finally, left with no option—at least the way he saw it—Rao took the ‘shortcut’. Just that once.

THE DOMINOES

In November 2011 OnMobile’s finance department received a set of bills from a vendor they hadn’t dealt with before. The bills amounted to nearly Rs 12 crore—a large enough sum to set alarm bells ringing. They had been forwarded directly by Arvind Rao.

Rajesh Moorti, the CFO who had joined the company in 2006 and played a critical role in its successful 2008 IPO, had resigned a few weeks earlier. The company’s board hadn’t made any serious efforts to ascertain why.

Now finance departments are adept at spotting irregularities, so the bills duly got flagged.

According to sources who were directly privy to what followed but chose to remain anonymous due to the nature of the incidents, the matter escalated to the attention of Mouli Raman, the CTO and co-founder.

On December 8, Rao was inexplicably divested of his role as chairman of the board. He continued to remain CEO and MD even as HH Haight, the 78-year-old head of Argo Global Capital, a venture capital fund that was OnMobile’s largest shareholder, became the new chairman.

The bills would remain stuck for another two weeks till Moorti left; they then got cleared.

But the dominoes had already started falling.

Two long-time independent board members—Sridhar Iyengar and JR Varma—resigned on January 24 and 25, respectively, a few days short of a scheduled board meeting on January 28.

Iyengar, a former CEO of audit firm KPMG India, headed the compensation committee while Varma, a highly regarded professor of finance at IIM Ahmedabad and a former full-time member of SEBI, headed the audit committee.

No reasons were given for their sudden and near-synchronised resignations.

Sandhya Gupta, OnMobile’s head of mergers and acquisitions, was asked to leave the company around the same time. Gupta was a close confidante of Rao and also a director and shareholder with him in four separate companies—RiffMobile, Mobile Traffik, Oskar Habitat and Aakar Investment.

Sanjay Uppal, OnMobile’s COO, was reassigned to a significantly reduced “advisory” role focussed on only the US market. Sanjay Bhambri, head of the company’s Asia-Pacific and Middle-East business, resigned.

It is understood both resignations were linked to the serious deterioration of the relations between Rao and the senior employees.

OnMobile’s board chose not to make any of this public.

In March, Amit Rastogi, a 15-year veteran at GE and OnMobile’s new CFO, wrote a letter to the audit committee of the OnMobile board. In it he raised issue towards the same set of vendor bills that had been paid out during the gap between the exit of his predecessor Moorti and his own joining.

It is learnt the letter had another signatory, Mouli Raman.

On April 10, Rastogi resigned, a little over two months after coming on board.

Again, the OnMobile board chose not to make the letter or Rastogi’s resignation public. But behind the scenes, Rao’s fate had been sealed.

Through its legal representatives Amarchand Mangaldas and Suresh A Shroff Advocates, KPMG, the firm’s internal auditor for over two years, was given a special mandate to analyse the transactions pointed out by ex-CFOs Moorti and Rastogi.

On May 25, six weeks after Rastogi had resigned, OnMobile informed stock exchanges of the event and the appointment of a new CFO, Rajesh Kunnath.

On June 1, it announced that Rao, though still CEO and MD, would look after only international customers while the company’s day-to-day operations would be overseen by a special board committee. The move to “free up” Rao’s time was part of the “OnMobile 2020 global strategy”, said the company.

But on June 28, after business news channel ET Now broke the news of Rao being under investigation for alleged financial misappropriation, the cat was out of the bag.

In spite of a hurriedly drafted announcement a day later denying press reports, there was no going back.

On July 9, the company announced that Rao had resigned as CEO, taking responsibility for certain “weaknesses in processes,” even though none of those lapses apparently caused any financial losses for the company.

The company was able to claim that because the approximately Rs 12 crore that had been paid to the external vendor was subsequently “returned” to OnMobile.

“Two CFOs and two independent directors resigning in such a short period shows there is something wrong. Since OnMobile is a listed company, its board has to come clean. They should put the forensic audit report in the public domain. And I hope the auditors too take cognisance of the forensic report in their report to shareholders. For far too long governance issues have been swept under the carpet by boards in India,” says TV Mohandas Pai, former board member and CFO of Infosys, and a widely regarded expert on corporate governance.

ARVIND’S DREAM

In October 2008, a few months after OnMobile’s successful IPO, Rao turned 50. On his birthday he bought himself a yacht, the Sun Odyssey 54 DS, a 54-foot cruiser made by the French company Jeanneau. Costing over a million dollars including taxes, “Avi’s Ark”, as Rao would christen it, would be one of his rare indulgences.

Unlike many who acquire yachts for their snob value, Rao truly treasured the sailing experience, making it a point to take at least a week off each month to savour the oceans.

His wife’s death in 2006—they had been married 25 years—had robbed him of his best friend and strongest mooring to life. With no children to look after, sailing gave him the time and space to get over that enormous loss.

He had one other obsession though, his baby.

OnMobile was an all-consuming obsession. He had been roped in by Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani in 2000, to take charge of the company’s fledgling Internet-based software product OnScan.

He got Tony Haight, the CEO of Argo Capital, to invest money to own over 60 percent of the company.

After OnScan’s initial business model failed in the wake of the dotcom crash, Rao shut down the US operations and refocussed on the Indian telecom market. Working out of Infosys offices in Bangalore, he, Mouli and the rest of the team worked round the clock to create a new product for mobile operators.

The break they were looking for came in November 2001 when Orange (which became Hutch, and then Vodafone), became their first customer. But instead of paying them licence fees for their VAS software, it offered only a share of actual subscriber revenues.

With their backs to the wall, the OnMobile team had no option but to take the deal.

Under Rao OnMobile went from operator to operator and its software platform quickly became the foundation for most operators to sell their VAS services from, earning OnMobile a cut of every subscription sold through it.

Rao’s impeccable academic credentials—degrees from IIT-Bombay and Wharton School of Business—followed by stints at consulting powerhouse McKinsey and private equity funds The Chatterjee Group and Gilbert Global Equity Partners had given him the confident charisma of a leader who knew what he wanted.

As the Indian mobile growth story started playing out, Rao and OnMobile rode the wave. By 2007, it was clocking annual revenues of over Rs 200 crore.

Rao had by then become the largest individual shareholder in the company, with a stake of roughly 14 percent. In contrast, Infosys, the company that had incubated and nurtured OnMobile, found its own stake diluted from 17.8 percent in OnMobile Systems (the US company) to less than 8 percent in OnMobile Global (the Indian one). Infosys co-founder SD Shibulal and board member V Balakrishnan are also thought to have been affected, as they held individual stakes in OnMobile Systems.

This led to the souring of OnMobile and Rao’s relations with Infosys, causing the latter to even complain to SEBI in 2007 against OnMobile’s planned IPO.

But after the resounding success of OnMobile’s IPO, Rao really didn’t care. After listing at Rs 521 per share, giving it a market capitalisation of over Rs 3,000 crore, OnMobile shares would go up to nearly Rs 700 over the next year.

Everything seemed to be going for him and OnMobile.

THE BURNING PLATFORM

In February 2011, Stephen Elop, the CEO of Nokia, wrote a 1,300-word memo to all Nokia employees criticising Nokia for standing too long atop its “burning platform” while competitors like Apple, Google and MediaTek innovated and disrupted away its leading market share.

OnMobile too is on a similar burning platform today.

Nearly 80 percent of OnMobile’s revenue comes from two sets of products—the caller tune and voice-driven subscription services. And though its share of the caller tune market in India is estimated at over 60 percent, beneath those numbers lies a stark reality.

Its 19 percent annual revenue growth rate this year masks the fact that it has undeniably peaked in the Indian market, and is in fact in a state of decline. OnMobile’s India revenue shrank by 9 percent during the year, compared to a growth of 94 percent on the international side.

Annoyed mobile subscribers and a strict regulator (TRAI) have taken their toll on the VAS services OnMobile can sell each month. Its largest customers have started implementing their own ‘service delivery platforms’ that can handle customer subscription and billing, thus relegating OnMobile to being just a content provider among dozens of others.

Rao has to shoulder some of the blame for this. Under him OnMobile became a very sales-led organisation, where the incentives were aligned towards ‘selling’ than ‘innovating’. The focus was on ‘pushing’ its existing products on new subscribers than identifying new products that fit consumer needs.

“Employees were so busy selling RBTs (ringback tones) all these years that they had no idea of what consumers really wanted,” says a person who worked for OnMobile at a senior level.

On a personal level, Rao’s decision to partner with Sandhya Gupta in multiple firms, some of which had vendor relationships with OnMobile, was a patently bad move. While he and OnMobile may have disclosed the companies are “related parties”, it is never a good idea for a CEO of a company to also be its supplier.

To Rao’s credit though, he did attempt a major restructuring last year from an operator-led model to a horizontal, region-led one. But with the organisation caught up in a downward spiral currently, it remains to be seen how that move will pan out.

Rao’s decision to aggressively sell OnMobile’s existing products and services in other countries has worked out quite well. Nearly 50 percent of its current revenues come from outside India, and often at higher profit margins.

But with him gone, it will be tough for OnMobile to pull off these plans.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT

Henry Huntly Haight IV, the 78-year-old chairman of the OnMobile board, has suddenly found himself thrust into the role of a hands-on saviour.

Haight is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of venture capital, especially in Asia. Haight is known to be a keen judge of entrepreneurs and in backing the good ones all the way.

He had implicit confidence in Rao, whom he had known even before the OnMobile days.

As an investor, he had learnt over the decades when to put the interests of his investors above his own. Under his guidance, the OnMobile board had first decided to create a new CEO position for its domestic business and operations, reporting directly to it. But with Rao’s resignation, perhaps that move was moot.

It is here that Mouli Raman, the soft-spoken and reclusive CTO, may have a task cut out for him.

The architect of OnMobile’s underlying software platform, Raman had disengaged himself from day-to-day operational work during the last two years after noting that Rao and COO Uppal had taken on most of the organisational responsibilities.

Insiders talk of Raman taking off for months at a time, with no explanation. It was around February this year that Raman came back from yet another of his self-imposed breaks, one that started in September last year.

Now as acting MD, it is up to Raman to steady the ship and prevent a rapid drain of talent over the next few months. Universally liked and respected, he will need to improve his people-managing skills—a weakness the board is aware of—to bring together disparate teams and products into a common purpose. To survive.

As for Rao, the tempest which began with his undying belief in OnMobile and his acquiring an additional 1 percent of its stock, seems to have ended.

On July 12, Kotak Mahindra Prime, the lender with whom Rao had pledged his shares, sold over 32 lakh of his shares, representing over 3 percent of OnMobile’s total shareholding.

This brings down his OnMobile shareholding to around 10 percent, contrary to news reports that he was no longer a shareholder.

The needle on OnMobile’s reputation and valuation has swung so far to the negative extreme that it is now looking like a great asset for canny buyers. HDFC Mutual Fund, Goldman Sachs and Merril Lynch have, between them, bought over 30 lakh shares of the company in July.

The market is finally realising the value of his baby.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)