Why Su-Kam is looking up to the sun

Su-Kam founder Kunwer Sachdev built his company's fortune by cashing in on an unreliable power grid. Now, he's looking up to the sun for inspiration—and profit

When he turned 15, Kunwer Sachdev began helping his older brother sell pens to shops in Delhi. It was the late 1970s, and the nation’s capital was not immune to rolling blackouts, which increased in frequency during the sweltering summer months. Today, at the age of 52, Sachdev is the founder and chief executive officer of Su-Kam Power Systems Ltd, one of India’s largest back-up power companies. It manufactures inverters and other devices—which he didn’t have access to when he was growing up—that provide uninterrupted power supply so that electrical appliances such as refrigerators, air-conditioners and fans can function when the grid fails to deliver.

Power outages are still very much a part of life in India, including Delhi. In its most recent study, the World Bank reported that over 1.2 billion people, or 20 percent of the world’s population, don’t have access to electricity, of which more than 400 million live in India. For companies like Su-Kam that benefit when the lights go off, business has never been better. Su-Kam’s revenues for 2013-14 stand at Rs 1,200 crore, up by 20 percent from 2012-13.

These days, though, Sachdev has been paying close attention to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s promise of replicating Gujarat’s 24-hour power supply model across the whole of India. And industry analysts believe that this goal can be achieved over the next five to 10 years. It’s also why the first-generation entrepreneur, who attributes his success to his ability to plan for future needs, is looking up to the sun for inspiration—and profit.

Su-Kam is betting on individual home owners generating solar power to reduce their electricity bills. The majority of consumers currently plug inverters and UPS batteries to their appliances, which then charge and hoard power from the main grid. Sachdev has flipped this model: He has started manufacturing inverters and UPS devices that can draw power from solar panels, which Su-Kam began manufacturing in 2004.

“We started research and development [R&D] for regular inverters in 2000. We don’t have to do anything special for solar-powered products. I’m already dealing in batteries, which use direct current [DC]. Solar panels also use DC. All I have to do is replace the battery in a regular inverter with a solar powered one,” says Sachdev.

He may not have an engineering degree, but he knows the nuts and bolts of the technology Su-Kam is betting on. “We started manufacturing solar-powered products a decade ago, and today it accounts for 20 percent of our sales,” he says.

Su-Kam offers solar solutions for homes and businesses. Apart from solar panels and hybrid UPS devices, it manufactures solar batteries, inverters, home lighting systems and network management systems. Sachdev wants to decentralise the power generating process. Instead of setting up large projects (more than 25 MW) that harness sunlight and sell electricity to the government’s central power grid, Su-Kam is selling smaller 5 kilowatts (KW) to 1 MW solar-powered systems to villages and housing complexes.

“We don’t sell to the government, which involves sourcing land to generate the required 25-30 MW of power. Here, the customer provides the land and we provide the technology,” says Sachdev. “Whatever the solar unit produces will get ‘mixed’ into the customer’s normal power supply because of which a household’s bill will reduce. You recover the investment in a few years, and the burden on the government to generate more power is lessened.”

Sachdev’s solar solutions plans are intriguing because they form a sort of hybrid between completely decentralised solutions such as individual solar lanterns and large solar farms.

Su-Kam is still in the pilot phase of this project. Since the start of 2014, the company has installed solar products—which provide eight to 10 hours of power supply daily—in 1 lakh homes across India. And it says that exports to more than 70 countries account for 15 percent of its sales (both regular and solar-powered devices). “We have a presence in African nations, but we are seeing that the highest demand for solar products is in India itself,” says Sachdev. This is why he has scaled up R&D in solar products at his Gurgaon facility. Five years ago, barely two out of the 45-strong team of engineers researched this sector. Today, it has evolved into a unit of 15 engineers.

Ashish Sethi, who heads Su-Kam’s solar business, recalls how, a few months ago, the R&D team produced a one-off (not in the company’s catalogue) solar product as per the specifications of a customer in Uttar Pradesh. “We did it in 48 hours,” says Sethi who believes that by 2018, Su-Kam’s solar arm will grow from its present Rs 250 crore business to a Rs 700 crore one. The company, however, has had its fair share of problems. An industry analyst who did not want to be named told Forbes India that Su-Kam was hit by quality and service issues three years ago. “Peripheral competitors like Exide and V-Guard also stole market share,” says the analyst. Two years ago, profits lagged and Sachdev fired 400 members of the service staff.

Sachdev acknowledges Su-Kam’s not-so-stellar performance in 2011. “We realised that we were starting to fall apart because we had too many people and no systems or structures. When we got major external funding, my people wasted a lot. I was also part of that,” he says. Apart from developing the solar business, creating a solid management and hiring system is an important part of his agenda.

He’s refreshingly candid about the mistakes he’s made. Perhaps it’s a sign of an entrepreneur who is not burdened by investor expectations. Though Reliance Capital and Temasek Holdings picked up a combined 20 percent stake for Rs 45 crore in 2006, they seldom interfere with operations. His investors trust him, he says. “Few companies have done all the groundwork necessary to reap the benefits in the next five years,” says Amitabh Mohanty, head of debt strategies at Reliance Capital (of the ADAG stable).

That said, eight years is a long time in private equity circles and investors will be waiting (and hoping) for the solar business to take off so that they can make a profitable exit. Success will depend on whether a company can stay relevant to India’s evolving power needs. And Sachdev believes he’s on the right track.

He wants to be seen as a social entrepreneur delivering clean energy to villagers. But he’s also a businessman, one who knows what it’s like to be bound to the whims of a capricious power grid. If Su-Kam can find a model to deliver and service solar generators to clusters of homes (particularly in rural areas), it can provide light and improve their standard of living by powering fans, televisions, mobile devices, and so on.

Like many of the customers he wants to reach out to, Sachdev, the son of a railway clerk who went to a Hindi-medium government school, hails from a lower-middleclass family. His is the quintessential rags-to-riches story. While helping his brother build a writing instruments business, Sachdev graduated from Hindu College in 1984 with a Bachelor’s degree in statistics. He later parted ways with his brother and got a law degree from Delhi University.

Bitten by the entrepreneurial bug, he set up Su-Kam—a cable TV accessories company—in Delhi’s Punjabi Bagh in 1988 with Rs 10,000. The fact that he didn’t have an engineering degree did not deter him. He picked the right business and, by 1998, the cable TV sector in India was booming. Sachdev says he was making a tidy Rs 3-4 crore as annual turnover.

But 1998 was also a turning point for the entrepreneur and, by extension, for Su-Kam. Power cuts were a frequent occurrence, and he recalls that the inverter in his house kept breaking down. He started researching the business and found that it was a largely unorganised industry. He also realised that it was an untapped sector, primed for growth in keeping with India’s accelerated development at the time.

In two years, he moved away from the cable TV industry and began developing and manufacturing inverters. In 2002, Su-Kam’s revenues stood at Rs 10 crore, and by 2004 they had grown to Rs 100 crore. It may have taken Sachdev just two years to grow Su-Kam tenfold but, after 2004, as the industry became more organised, it took him a decade to grow another tenfold. Also, it’s hardly the only inverter company to make the logical move to solar.

In 1991, when Su-Kam was still selling cable TV accessories, businessman and engineer Rakesh Malhotra’s Luminous Power Technologies started manufacturing its first inverters. In 2011, Malhotra sold a 74 percent stake in Luminous Power Technology to European giant Schneider Electric for Rs 1,400 crore. It is now a leader in the Rs 8,000 crore Indian inverter and UPS market (by revenues) with Taiwanese-owned Microtek in the second place, followed by Su-Kam. In 2011, Luminous also launched solar products, which brought in 10 percent of revenues in 2013.

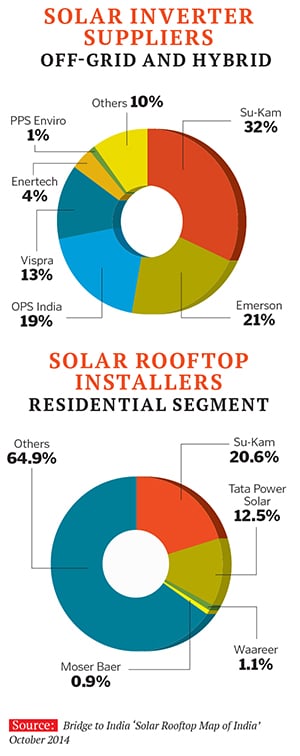

Although Sethi claims that Su-Kam is a leader in the solar UPS business, experts say it’s not easy to verify this claim because the green energy sector is fragmented and niche. Most of the companies operating in this arena are either unlisted or subsidiaries of multinationals, and data is hard to come by. Sachdev is wary yet respectful of competition. “People think Schneider bought Luminous for the brand; they bought it for the technology. Foreign companies have to buy Indian technology even if they want to expand to Africa,” he says.

At the same time, he accuses local rivals of copying his products and laments India’s slow patent regime for allowing it. “We have filed the highest number of patents in the world in our industry, but yesterday I wrote a letter to PM Narendra Modi asking how he would implement his ‘Make in India’ plan if it takes seven to eight years to grant a patent.”

A valid concern given that Sachdev is hoping to make hay while the sun shines.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)