Yogesh Mahansaria's Second Coming with Alliance Tires

In 2006, Yogesh Mahansaria was turfed out of the business he had built, Balkrishna Tyres. That’s when PE player Warburg Pincus took him on board to give him a second crack at success. Seven years on, with Alliance, he has come back with a bang. And Warburg is counting its shekels

Yogesh Mahansaria

Age: 38

Business mantra: If you want to be a good steward of the business, you cannot let family come in the way. “I would not let my personal ownership stake get in the way of building a global, world class business.”

Belief: Deeply religious. Stays opposite Mahalaxmi Temple in Mumbai and visits a temple four times a week. “I thank god for choosing me to be so lucky. And ask that my good luck continues.”

Passion: Other than tyres, it is watches and pens

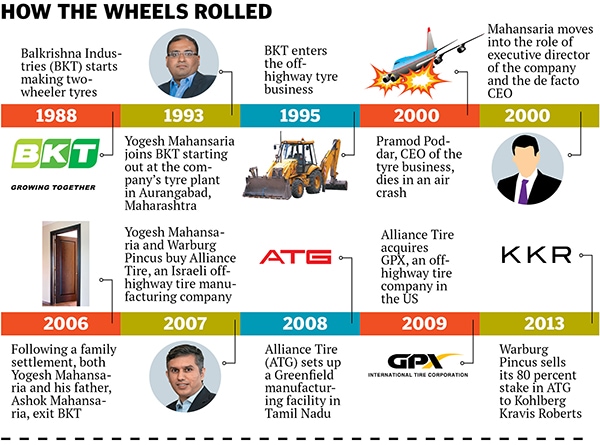

Around December 2012, there was an unusual buzz in the private equity (PE) industry. Warburg Pincus, one of the world’s largest PE players, was selling its 80 percent stake in Alliance Tire Group (ATG), the world’s sixth largest off-highway tyre manufacturer with revenues of over $500 million and profits of around $100 million. A company promoted by Yogesh Mahansaria.

Yogesh who? Exactly. Not that ATG is any better known. As one PE investor put it: “Off-highway tyres are not on anybody’s radar. It is not the typical consumption story in India; not the typical infrastructure story either.” But interest was high. Blackstone, Advent International, Temasek and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) were among the suitors lining up to make a bid. After almost five months, KKR emerged the winner.

In April 2013, KKR bought a 90 percent stake in Alliance at an enterprise value of about $650 million. The Mahansaria family kept a minority stake. This was the biggest PE transaction in India since Bain Capital paid about $1 billion for 30 percent of Genpact, the business process and technology services provider, in August 2012. Sanjay Nayar, CEO of KKR in India, says “One had heard about Alliance but we didn’t know Yogesh or the company very well. We got involved because Warburg was running a sell-side process. But when we met the management team we realised there was a niche, which ATG had done a terrific job of capitalising on. There is a pretty big opportunity in helping Alliance penetrate that segment further.”

According to PE industry sources, Warburg may have reaped almost four times the amount it invested in Alliance. This would make it the firm’s most successful investment after its Bharti Tele-Ventures exit in 2005. Obviously, no one could have predicted this in 2006.

If Alliance Tire was another feather in the cap of Warburg, which tops this year’s Forbes Dealmaker 50 list, it was also the vehicle used by Mahansaria for his second coming. Over the last 20 years, Mahansaria has built not one but two large global businesses from scratch. On both occasions, he has made money for his investors without bothering about his own stake in the company.

OUSTED

Yogesh Mahansaria’s career hit a low in 2006, when he made an unceremonious exit from Balkrishna Industries (BKT). Seven years on, it is still a sensitive subject. Broach the topic and he winces.

“That’s a personal issue I would not like to comment on,” he says. We try again, rephrasing the question. Was the family settlement amicable? There is silence. Mahansaria searches for words but with little success. What he does not deny is the sense of something left half-done. “When I exited the company, there was the feeling that my journey was only half complete. There was a lot more to be done which, due to circumstances, we could not do. Obviously, after such a long tenure, when one leaves, there is always a little bit of…” he tails off, leaving it to you to imagine what he felt when he got turfed out of BKT as part of a family understanding.

The attachment is obvious. In 1993, Mahansaria was just 18 when he entered BKT, then a loss-making company manufacturing two-wheeler tyres that nobody wanted. He formulated a gameplan that, over the next decade and more, took BKT global with revenues of Rs 632 crore and profit of Rs 70 crore. And this was the company he had to bid farewell to because someone else had a claim to the throne.

On July 8, 2006, Mahansaria resigned from his position as executive director of BKT, India’s largest off-highway tyre manufacturing company. His father, Ashok Mahansaria, also stepped down from his position as the company’s vice-chairman and managing director. The duo had put in 12 and 30 years, respectively, at BKT. But they were minority shareholders with a stake of 5.4 percent. The Poddar family, also owners of the Siyaram Group, were the majority shareholders and wanted the Mahansarias out of the way. Arvind Poddar and his son, Rajiv, wanted to take over. The Mahansarias resisted, but they had neither say nor stake. So they walked.

In the process, they set the stage for a bigger comeback.

The billion-dollar opportunity

If there was ever a list of non-sexy businesses in the world, manufacturing off-highway tyres would certainly figure somewhere near the top. Mahansaria says he doesn’t mind that as long as there’s money to be made. The way he looks at it, there’s a billion-dollar opportunity in off-highway tyres, and he’s only halfway there.

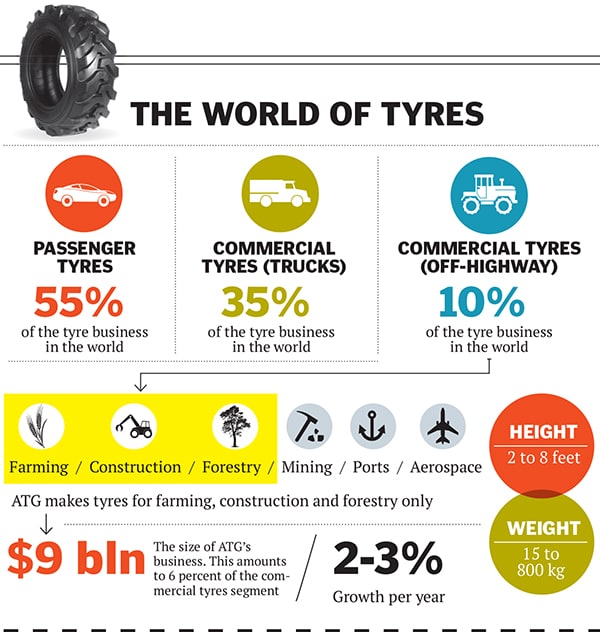

Off-highway tyres are a $9 billion industry globally, about 10 percent of the global tyre market. These tyres are big—from two to 10 feet high—and heavy, ranging from 15 kg to 1,000 kg per tyre. Manufacturing is labour-intensive. Companies need to have a huge number of stock keeping units (SKUs, or the number of size variations in the same basic product). Alliance, for instance, has more than 2,000 SKUs. Compare that to a passenger tyre where, with just one SKU, companies can churn out a million units. This industry comprises several verticals: Tyres for agricultural, construction, forestry, mining, ports and aviation equipment. ATG operates in three of these, agriculture, construction and forestry.

Take agriculture. The world’s population is growing. The land area available for agriculture is shrinking. Productivity needs to increase. Which can only happen through more farm mechanisation. And, as Mahansaria puts it, “more machines mean more tyres.” A similar story is unfolding in the construction industry. If you look beyond business cycles, the infrastructure needs of countries like India, Russia and Brazil, among others, are only growing.

Further, very few people in the world are interested in making off-highway tyres. The Bridgestones and Michelins of the world prefer to focus on passenger, commercial and mining tyres. “In the last five years, the market share of the big players has dropped from close to 50 to 35 percent. And because this is a low-volume, high-SKU business, no Chinese players are interested. So this is a great opportunity for companies like Alliance and BKT,” says a mutual fund manager who has invested in BKT but does not want to be quoted.

Even if the industry’s compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) is of just 2-3 percent, for a $9 billion industry that means a $160 million incremental market every year. Take a five-year compounding and that’s another billion dollars. Mansaria says, “So if Michelin, Bridgestone and Goodyear are not increasing their capacity, it is a big addressable market for us. In five years, the incremental market opportunity is twice my current revenues.” And that’s his destination: Alliance as the largest off-highway tyre manufacturer in the world.

Ironically, none of this ambition or wisdom would have dawned on him if he hadn’t joined BKT in the first place.

The Circumstances

At 5’7, Mahansaria looks every bit the Marwari he is. Born and brought up in Bombay (Mahansaria never says ‘Mumbai’), he was a bright kid in school but his academic performance at Sydenham College was unflattering. “I completed [a Bachelor of Commerce degree] with a lot of persuasion from my parents. I don’t even know what my marks were. I joined the family business while I was studying.”

BKT had a small plant in Aurangabad which made scooter and motorcycle tyres. “I spent three years [while still in college] there, learning about tyre production, machines, technology and all the things that go into the production process.”

Business, though, wasn’t doing all that well. BKT’s turnover was around Rs 40 crore in the early 1990s, but it was barely profitable. Things turned for the worse, though, when tyres went into an over-supply scenario. BKT didn’t have the size or the money to compete with the larger companies like MRF. “That was when the family was thinking about what to do. We had lost money for 10 years.”

There was a glimmer of hope after the government announced tax incentives and duty waivers: Mahansaria was asked to travel and scout for export potential. “Pretty soon I figured out that nobody wanted scooter tyres from India… because there were very few scooters outside of the country.” What the world wanted, instead, was small, farm tyres. As long as it was tyres they wanted, Mahansaria says, it felt like a good opportunity.

BKT’s 1995 foray into farm tyres started with a small project for a customer in the UK and for another in the US. “We were lucky we had people willing to take that punt on us. We were able to deliver to their satisfaction but it is not like the floodgates opened immediately.”

Then tragedy struck, in 2000, when Mahansaria’s uncle, Pramod Poddar, the then-CEO of the company, passed away in an air crash. Mahansaria was just 25 at the time. He had to run the business himself for a while. He had his first brush with strategic choice when he discovered that the money earned from exports was being lost in serving the domestic market for two-wheeler tyres. “I realised we were too small as a company to ride two horses at the same time. We took the decision to close the business. It was challenging, dealing with customers who had been with you for a long time and to let go of people.

Those weren’t easy decisions but I think it was the right path for the company.”

The strategy paid off handsomely. “It took us five years to go from zero to $10 million and another five years to go from $10 million to $120 million.” And in less than 10 years BKT went from the smallest and most inconsequential to the largest and most profitable business within the Siyaram group. This didn’t escape the attention of its founders, the Poddar family; and the next generation was keen and ready to take control. A family member told Forbes India on the condition of anonymity that Mahansaria’s departure was anything but amicable: “He was basically asked to go. We were in our teens then, and I remember the elders saying that what was happening was not right. But there are certain decisions that have to be made.”

Mahansaria himself says only this: “The family was expanding and other members were coming into business. Everyone had their own aspirations. My father and I thought it was the right time for us to move on.”

After BKT, Mahansaria says he was clear about just two things. One, he wanted to build a large, global business. Two, he would prefer to build tyres. The question was, how?

The Warburg Pincus Connection

Just as the Mahansarias were moving out of BKT, Warburg Pincus reached out to them.

Vishal Mahadevia, co-head along with Niten Malhan at Warburg Pincus, India, says, “As a firm we have known Yogesh, and we followed him as he built BKT. We couldn’t do anything with him then for a number of reasons. Once he quit BKT, we had a chance to sit with him and his dad.”

In Mahansaria, Malhan and Mahadevia found a man absolutely clear that he wanted to build a scale business, preferably in off-highway tyres. Unlike other entrepreneurs, Mahansaria wasn’t worried about ownership or stake. As Malhan says, “He understood that to [build a scale business], the capital could not come only from him. There is often a case for not-strapping, starting up and, over time, getting there, but in his case he said, ‘Look, I see an opportunity, and it is not going to be there forever because someone will fill it; if I can accelerate that process through accessing capital, it can help getting there more quickly.’”

Both Warburg Pincus and Mahansaria needed a platform on which to build. That opportunity presented itself when a rich man in Israel found himself in trouble.

The Alliance

The year 2006 was a tough one for Eliezer Fishman, the owner of Fishman Holdings and one of the richest men in Israel, with investments in real estate, media and a tyre company called Alliance Tire. In May 2006, he suffered losses of about $400 million when the Turkish lira plunged 20 percent and forced him to sell many of his assets. Alliance, listed on the Tel Aviv stock exchange and the only off-highway tyre company in Israel, was on the block. It had made a loss of $7 million that year. Its business model, though, was similar to what BKT had evolved to under Mahansaria: It was an offshore producer, specialising in agriculture tyres and exporting to Europe and the US. The only difference, though, was that while India has remained low-cost, Israel over a period of time went from low to high-cost.

“I got to know about the Alliance situation from an industry colleague,” says Mahansaria. “I had known the company over the years, because they were our role model. We realised that buying Alliance and coupling it with a greenfield plant in India de-risked the strategy. In one shot you would get the brand, distribution, the product library, each of which is a significant competitive barrier in this business.”

This wasn’t the easiest decision to make. Israel was in the middle of a war with Lebanon and nobody knew what shape it would take.

An unexpected saviour appeared in the form of Warren Buffett. In 2006, Berkshire Hathaway paid $4 billion to buy an 80 percent stake in Iscar, a metalworking company in Israel. Mahansaria says, “I remember Warburg telling me, ‘Why are you worried? If Warren Buffett can spend billions of dollars buying a company in Israel, you know he has done his homework; the country is not going anywhere.’ To my mind, to have a risk appetite like that when it was just a plan, it is gutsy.”

In August 2006, Warburg Pincus and Mahansaria made a bid for Alliance. The company turned it down saying the offer was too low. They bid again, this time about $48 million, plus Alliance’s debt of about $100 million. It sailed through but it wasn’t before July 2007 that the deal was finally closed.

It came with its fair share of challenges.

Mahansaria, who had never made an acquisition before, says the process was a huge learning.

The first lesson was patience. Delisting the company and dealing with lenders, because it was a highly leveraged company, was painstakingly long. “It was frustrating because you are sitting in this room, with all these lawyers and all the blah, blah, blah going on; it is so non-value-adding. If we had tried to do this on our own without Warburg, then we would have given up in a couple of months because we would have felt it was a waste of time.”

The second lesson: How to restructure a business in a foreign country. Mahansaria says that when he first went around the plant in Hadera, Israel, he could see that the people were mostly home-grown talent who weren’t experts. There was no benchmarking of operations against world-class locations. People weren’t forthcoming either. “The first time I walked in the plant, I asked the plant manager about the efficiency at which the plant was running. He said 80-85 percent. It didn’t feel like that to me. I asked for data rather than debate in the absence of it.” That didn’t arrive for almost a month. “I had to literally coax that paper out of them because when they put the data on paper, it was clear that the efficiency was 60-65 percent. That is the biggest challenge we faced there: These were people with a very defensive mindset.”

Over the next three years, he replaced a significant chunk of the senior management with experts from Turkey and India. Almost 300 people were asked to go. Manufacturing of high-volume, low-margin products was moved to India, thereby freeing capacity to make only high-margin products.

And even as Mahansaria was getting Alliance back on its feet, another opportunity came along in 2008, in the form of GPX International in the US.

The GPX Impetus

In 2007, when Craig A Steinke took over as CEO of GPX International Tire Corporation, a Massachusetts-based tyre manufacturer and importer, he could scarcely have foreseen that in just about two years’ time, his company would be hurtling towards bankruptcy. GPX started life as a scrap and surplus tyre dealer in 1922 but, by 2008, it had grown into a large corporation with a turnover of over $500 million.

It was then that its journey was interrupted.

In late 2007, trade battles between China and the US had intensified. GPX, with a plant in China, found itself in the middle of the dispute.

Titan International, one of the largest off-highway tyre manufacturers in the US, filed a petition with the US Commerce Department and the International Trade Commission against GPX, alleging that the company was dumping its products in the US. Eventually, the Commerce Department slapped a 44 percent duty on GPX in 2007. This spelt disaster for the company.

In mid-2008, Steinke reached out to Warburg Pincus to check if Alliance would be interested in buying the company. He had worked with Warburg in his earlier assignment, as CEO of Eagle Family Foods Holdings. Warburg checked with Mahansaria if it was worth a meeting. As things turned out, Mahansaria knew of GPX and its founders, the Ganz family. It was a great fit. The Alliance acquisition had already got him into agricultural tyres in Europe; GPX would give them a strong US presence in forestry and construction.

A meeting was set up. Mahadevia says, “Niten and I, when we were in New York, met the CEO [Steinke] to get to know him personally, understand his views on the business and his plans. Yogesh set up a meeting separately with the founders at the same time. The whole dialogue was, ‘Here’s what I like, here’s what I don’t like; how can we structure a transaction?’”

Even as negotiations were on, the world was hit by the Lehman Brothers crisis in September 2008.

Things slowed down; Mahansaria wasn’t sure if he should go ahead with the buy. “I told Warburg, look the world is coming to end, should we be doing something like this right now or should we be focusing on the existing business? They said it was a great opportunity: Let’s just go ahead and do it. We will have some bumps along the way but we will deal with those,” he says. In October 2009, GPX filed for Chapter 11, with Alliance Tire as the stalking-horse bidder for its US operations. (A stalking horse bidder is an initial bid on a bankrupt company’s assets from an interested buyer chosen by the company itself.)

However, the bankruptcy court asked GPX to get competitive bids. As fate would have it, Maurice ‘Morry’ Taylor Jr, a former Republican presidential candidate—and, incidentally, CEO of Titan, whose lobbying for anti-dumping duties on GPX led to its bankruptcy—made a bid. On December 8, 2009, Alliance Tire and Titan International arrived at the GPX auction in Boston.

Mahadevia says, “We sat in the courtroom with our counsels and the other bidder’s counsels arguing.” The judge finally asked Mahansaria and Taylor to sit side-by-side and start bidding.

Mahadevia says that this is the time when a fully aligned partner helps an entrepreneur. “Ultimately, Yogesh has to take the decision to bid X million more and win this because it is strategically important. We had five minutes to decide. Then the judge comes out and says your time is up and we are like come on, just one minute!” In the end, Alliance won the bidding war and acquired GPX for $54 million. Of course, Taylor was anything but pleased. He stormed out of the room. “I think they have overspent for what they’re getting, which is good for us since they won’t have much left over to spend on other activities,” Taylor told Tyre Business later in an interview.

The Business He Wanted

Mahansaria was happy when the whole episode was over. More importantly, all the pieces had come together: He now had a global company in his preferred business.

As far as Warburg was concerned, it had done everything it could to help Mahansaria get to where he wanted. “Basically this was a startup where there was a vision. And we were buying platforms. The first three years of this was, for the lack of a better word, scrambling the egg. We were building the foundation of what would eventually become ATG and, in 2011, we started to see it all come together,” says Mahadevia.

Both Warburg and Mahansaria believe the story of Alliance holds an important lesson for entrepreneurs: Build value over shareholding.

Mahansaria says that when he quit BKT, there was a choice before him: Build a small company with a majority stake; or go with Warburg and create a large global business.

“I have built two businesses. The first time round, my journey was interrupted. I want to take Alliance to where it should be: The world leader in its business. As long as my partners are aligned with that vision, I would not let my personal ownership stake get in the way.”

Unlike the high-stepping banker types, PE investors like to stay detached, even blasé. They tend not to celebrate transactions; a quiet little dinner at most. But with the Mahansaria story, perhaps the folks from Warburg will unbend a little and break out a magnum of Champagne?

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)