Are Nanoparticles a Health Hazard?

Nanoparticles are a mega business opportunity for multinationals but they may pose a health hazard to users

There is a new industrial revolution taking place all around us. The only problem is we can’t see it.

The building blocks, being developed at the cost of billions of dollars by scientists, governments and multinational corporations, are just a few atoms or molecules thick — nanoparticles. Many are less than 100 nanometres (nm) — one-billionth of a metre — thick. A single human red blood cell in comparison is around 500 nm in diametre.

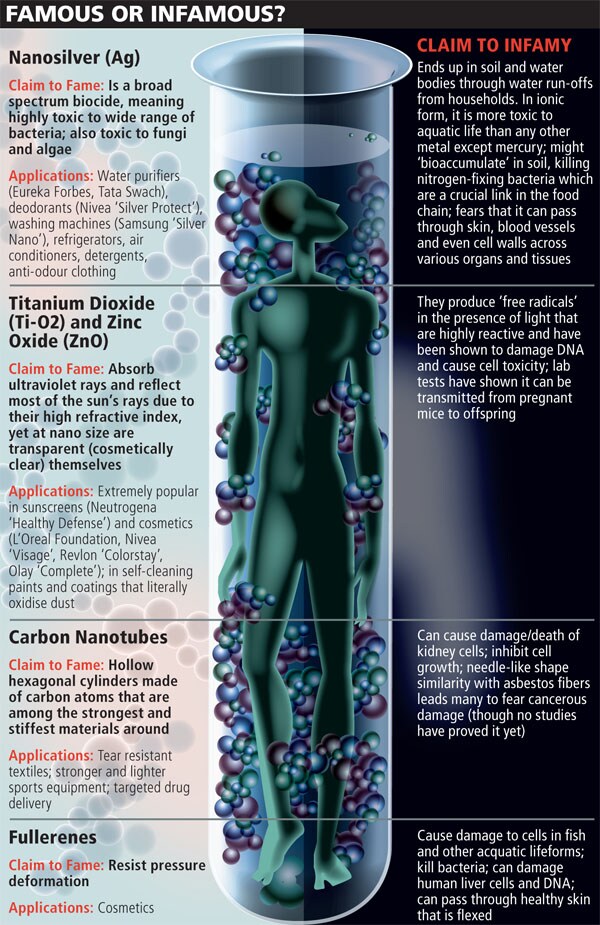

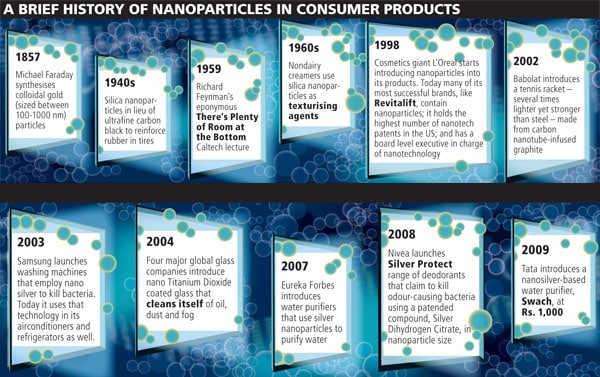

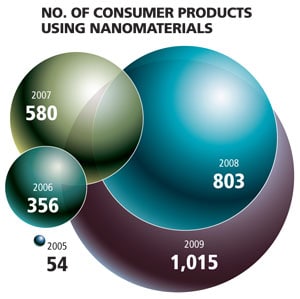

It’s a pity though that our eyesight isn’t good enough at nanometre level, for if it were, we would see that nanoparticles of precious metals like gold, silver and titanium have already made the jump from research labs to our homes. Manufactured nanoparticles are today present in thousands of consumer products around the world — silver in washing machines and water purifiers to kill bacteria, zinc in cosmetics to protect against ultraviolet rays, carbon nano-tubes in tennis rackets to make them stronger and lighter, titanium in household paints to decompose dust and grime without human intervention.

Nano is the New Black

“There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom”

So went the classic lecture by the Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman in 1959 that many nano-ficionados now consider the conceptual sun of the nanotechnology universe. “Why cannot we write the entire 24 volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica on the head of a pin?” he asked.

“Because there isn’t much of a point, or money, in doing so!” is the answer he would have got today from nanotechnology researchers. Instead their time is mostly spent figuring out newer properties for nanoparticles which can then be embedded into commercial applications.

Nanoparticles are highly reactive and prone to unusual properties. Describing gold, a metal that is normally inert to all other chemicals, Prof. C.N.R Rao, Honorary President and Linus Pauling Professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR) and the head of its Nanoscience centre, says “At 200-300 nm thickness, gold is not metallic, it does not shine — in fact it is not gold. And at 1.5-2 nm, it reacts like mad!”

Silver, an ornamental metal and a powerful bactericide, can be reduced to nanoparticle form to destroy disease-causing bacteria from all kinds of places — kitchen counters, contaminated water, dirty clothes and stinky underarms.

Silver, an ornamental metal and a powerful bactericide, can be reduced to nanoparticle form to destroy disease-causing bacteria from all kinds of places — kitchen counters, contaminated water, dirty clothes and stinky underarms.