Tribal Communities Stand their Ground

The territorial battle between mining companies and tribals has spread across the country

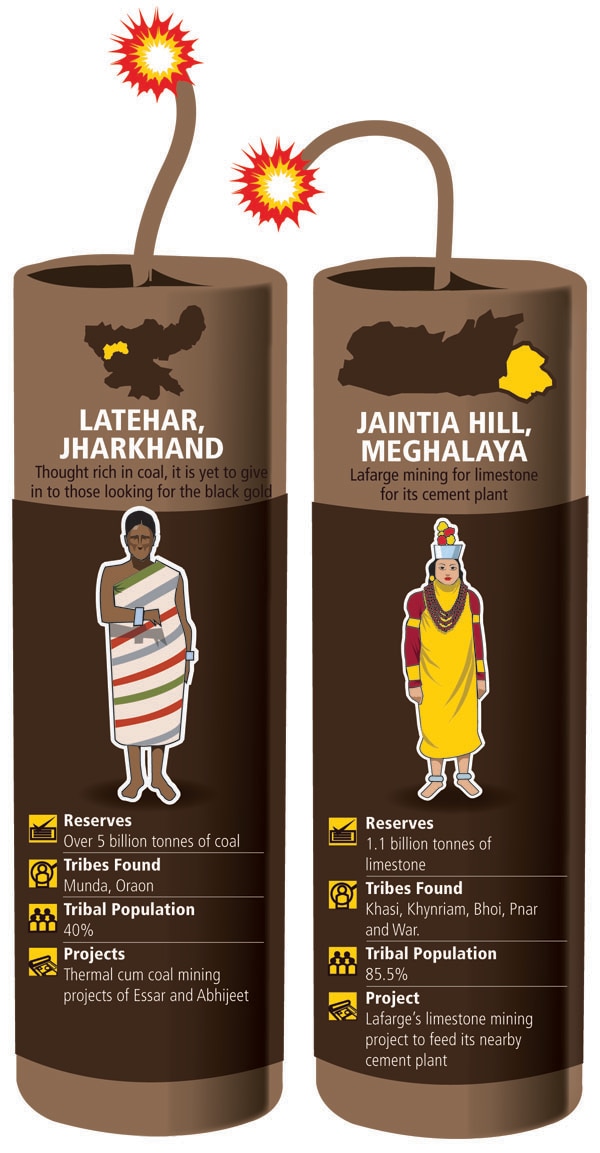

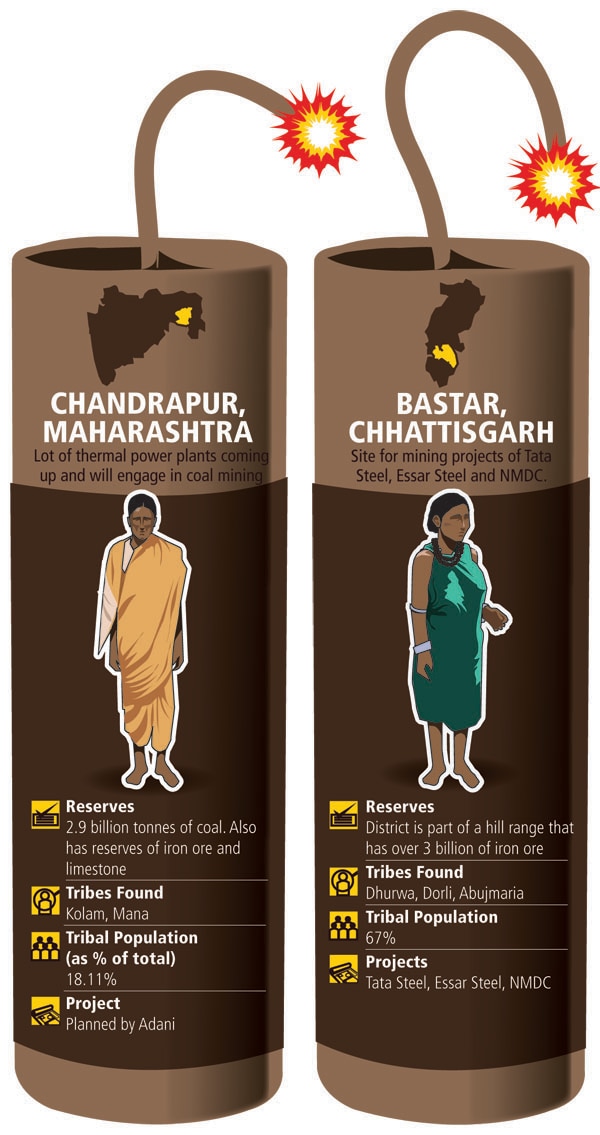

Latehar, Hazaribagh and Gumla in Jharkhand, Bastar in Chhattisgarh, Chandrapur in Maharashtra, the Jaintia Hills in Meghalaya… the list goes on. These are all districts in India where mining companies are locked in a battle with the local population over the mining rights in these regions.

Other than fighting mining companies, there are two factors common to all these regions. One, they have fertile land and dense forests. Two, indigenous tribes have been living on and off the land for generations. The tribals do not want to give up their lands for mining or for setting up power plants. They want to continue their traditional way of life. And this is one problem that will not disappear if you throw money at it.

Take Latehar for instance. The region has ample iron ore, bauxite and granite reserves. But its greatest treasure is coal. And companies of every size, from big ones like the Essar Group to lesser known ones like Abhijeet Group, want a slice of the pie. But the tribals in Latehar refuse to give up their land. They want to continue farming. This conflict, ostensibly between antiquity and modernity, is repeated in Chandrapur, Maharashtra, home to one of the oldest coal mines in the country. It is also a home to three-fourth of Maharashtra’s forests and tribes. Then there is the far-off region of Jaintia Hills in Meghalaya where French company Lafarge has been facing a resistance from the local population.

Tribals refusing to give up land is not a phenomenon unique to India. “There have been stand offs between indigenous people and mining companies in countries such as Australia and Brazil,” says anthropologist Felix Padel. “But nowhere is it as widespread as in India,” he says.

India has among the largest number of tribes in the world. But what makes Indian tribes unique is their geography. Across the country, India’s indigenous people live side by side with India’s most sought after natural resources.

This brings them into direct clash with India’s fast growing companies. “At the pace that we are growing, it is inevitable that we would need to develop our resources. It doesn’t make economic sense to import coal and iron ore when we have abundant of them,” says a senior official in a leading coal mining company. India also has an abundance of tribes. According to numbers from the government, there are 426 recognised tribes in the country.

Most tribals have lived off the land since generations. With almost no technical training, they are ill-equipped to benefit from the fruits of mining. And India doesn’t have a very good history when it comes to rehabilitation of displaced populations. Natural resources are the livelihood of tribals and they will fight tooth and nail for it. This was clear in the standoff between Vedanta Resources Plc and natives from the Dongria Kond tribe in Orissa. “Earlier it was thought that the tribals don’t want to give land because they are not happy with the money that was being offered. But that is not so. Today the rate per acre has gone up from less than a lakh of rupees to Rs. 10 lakh. Still the tribals don’t want to sell their land,” says Philip Kujur of the Ranchi-based Bindrai Institute for Research Study & Action, a self proclaimed mining and tribal rights awareness group active in Latehar.

It is clear that the path to India’s mineral pie is not an easy one. India’s economic model awaits a situation where the mining imperatives and tribal priorities can be harmonised.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)