Fortifying India via Bharat: Crisil's Ashu Suyash

The overarching theme of the government's policies, including measures announced in the Union Budget, is of revitalising rural India

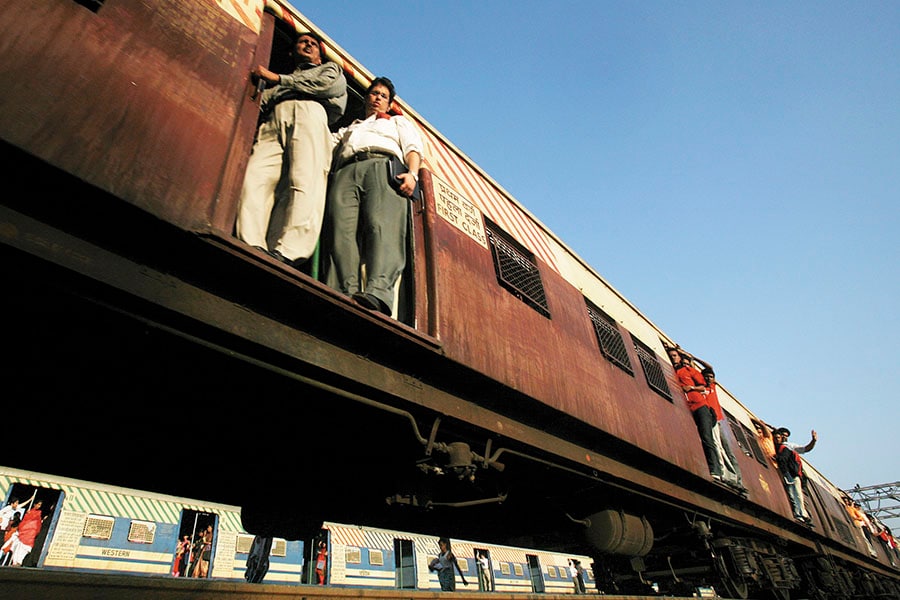

Image: Getty Images (for illustrative purposes only)

Focusing on little steps that add up to a growth marathon is a sensible strategy. Given that the hinterland has borne the brunt of a sluggish economy and two years of drought, attempts to rekindle it are empathetic. Also, given the potential headwinds—both exogenous and endogenous—this was a time for prudence. In any case, when the political cycle begins again later in the next fiscal, populism could be tough to resist.

Playing to the gallery was easier

The government’s emphasis is on bringing up the sidelined India, the one that lives in villages and has few options beyond the farm, and the one that lives in urban pockets but is condemned to penury. But equally, there is a focus on infrastructure and fostering transparency through leveraging technology, all with an eye on enhancing the economy’s long-term growth potential.

Spending on rural areas and poverty alleviation has shot up, with higher allocation to schemes such as MNREGA and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. Agriculture has got primacy, with measures for micro-irrigation, dairy farming, credit availability and farm insurance coverage, even as rural connectivity and liveability are expected to improve with steps to boost infrastructure, housing, sanitation and electrification.

Infrastructure allocation is up by nearly 10 percent, including a 24 percent jump for highways and a 22 percent jump for railways. Rail safety, too, has been given due importance with a Rs 1 lakh crore safety fund to improve train speeds and carrying capacity. For urban India, there is an 80 percent increase in allocation towards metro rail, with a new policy framework to encourage private sector investments.

Investments in building a strong digital infrastructure are set to improve rural coverage, critical to expansion of the digital economy. Allocation under the BharatNet programme has been budgeted at Rs 10,000 crore, a near-two-thirds rise over the previous year.

Given all this, the fiscal deficit target has slipped a notch to 3.2 percent of the GDP. The intention is to catch up in the next couple of years, despite likely hiccups in divestment and the Goods and Services Tax.

With the government’s net market borrowings restricted to Rs 3.48 lakh crore for the next fiscal, lower than the previous Rs 4.25 lakh crore, there is fiscal rectitude. Subsidies have been kept under a tight leash at 1.4 percent of the GDP, 10 basis points lower than the current fiscal. We estimate that the provision for fertiliser and petroleum subsidy would ensure there are no carry-forwards to the next year and all pending bills are paid out.

This will result in lower interest rates, and improve monetary and fiscal policy coordination.

The last piece of the jigsaw is improving India’s tax-to-GDP ratio. The government’s intention to use data analytics to mine demonetisation deposits, and the various measures to digitise the economy, will leave unprecedented transaction trails and improve tax compliance.

Growth next fiscal

In fiscal 2018, we expect a pick-up in GDP growth to 7.4 percent, compared with the expected 6.9 percent in fiscal 2017. The investment cycle is expected to remain weak; consumption will likely pick up moderately despite a cut in tax rates and softer interest rates.

Agriculture-related sectors will benefit from rural spend, and rising rural incomes will benefit makers of consumer goods, two-wheelers and tractors.

Demand has been a drag for some time, and demonetisation has affected this. But the thrust to rural consumption will provide a kicker, given that it contributes 55 percent to total consumption, and rural GDP is 47 percent of India’s GDP.

The focus on transport infrastructure should help construction, engineering, and cement and steel players, by cutting logistics costs and improving efficiencies. These players will also benefit from the push to affordable housing and irrigation.

Technology and telecom players will benefit from the digital push and programmes like BharatNet.

The real estate sector should be abuzz, thanks to easier funding for affordable housing, tax relief for unsold inventory, an expected spurt in demand from a softening rate environment, and deferment of payment of capital gains in case of joint development agreements. Infrastructure status will facilitate entry of long-only funds.

The reduction in corporate tax by 5 percent will leave more cash in the hands of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), which are the heart and soul of job creation and industrial enterprise. The emphasis on improving education and skill levels should improve availability and quality of labour, again underscoring long-termism.

As for the debt market, concessional tax rates for external commercial borrowings and capital gains benefits for masala bonds should support fund raising.

Challenges remain

A big miss is the lack of a road map to resolve the banking sector asset quality stress and capital woes. At Rs 10,000 crore, the capital allocated to public sector banks is woefully short, and will impact their ability to finance growth. Crisil estimates these banks will need Rs 43 lakh crore up to 2020, as a rising shift in market share to private banks and non-bank finance companies is already visible. This also underscores the need for efforts to deepen India’s corporate bond market.

In order for MSMEs to remain employment generators and an economic multiplier, the sector needs to leverage the subsidy scheme. But 90 percent of them cannot access formal credit. Doing something beyond the budget to mitigate this roadblock would be welcome.

In the housing sector, restriction on how much loss from house property can be set off against other income could thwart demand, and put pressure on capital values.

Further, boosters to consumption are conspicuous by their absence, especially given the slowdown in private consumption after demonetisation. That was necessary to improve capacity utilisation and business confidence, and revive the investment cycle.

- The writer is MD and CEO, Crisil

X