Going back to the roots

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar had famously said, "an India on the move is an India of churn". Those who have reached their hinterland homes are unlikely to come back in a hurry. What lies in store for them, and generations after them? One maverick tech entrepreneur may have an answer

It took a pandemic for urbanites to realise the plight of the multitude that moves from the hinterland for work. Images on social media of distressed citizens walking thousands of kilometres and spending days in trains that ostensibly lost their way seemed to have stirred the conscience of the chattering class who wanted to know: Why was this workforce that wanted to go home from the infested cities having it so bad?

The answer may well be that conditions for them have never been great, anyway. A 2013 Unesco publication titled ‘Social Inclusion of Internal Migrants in India’ points to some of the constraints that persist today: “Internal migrants are excluded from the economic, cultural, social and political life of society and are often treated as second-class citizens.” Estimated at close to 30 percent of the total population, many lack adequate housing, decent wages and are excluded from state-provided services such as health and education.

It took a pandemic to initiate reform. In end-May, The Times of India reported that the government will redefine who are “migrant workers” and register them so that they can access social security and health benefits.

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar famously said that “an India on the move is an India of churn” and, to be sure, faster economic growth over the past two decades has resulted in just that. According to the 2011 Census, the annual growth rate of labour migrants nearly doubled, rising to 4.5 percent per annum between 2001 and 2011, from 2.4 percent in the 1991-2001 period (source: 2016-17 Economic Survey). The problem, though, may well be that this economic growth is largely driven by commerce and industry in the urban hubs, even as agriculture’s contribution declines.

McKinsey a decade ago estimated that India’s city population will double to close to 600 million by 2030 (the World Bank in 2017 estimated the urban population to be at 34 percent of the total population, or a little over 400 million). The consulting firm reckoned that India needed to invest $1.2 trillion in core urban infrastructure in the two decades till 2030, eight times the 2010 spend.

The inadequate infrastructure and housing conditions suggest that Indian cities have not reached a position from which they can do justice to those who build, protect and clean their sky-scraping homes and offices, and run their shops, supermarkets, restaurants and transport. Those who have reached their hinterland homes are unlikely to come back in a hurry. What lies in store for them, and generations after them?

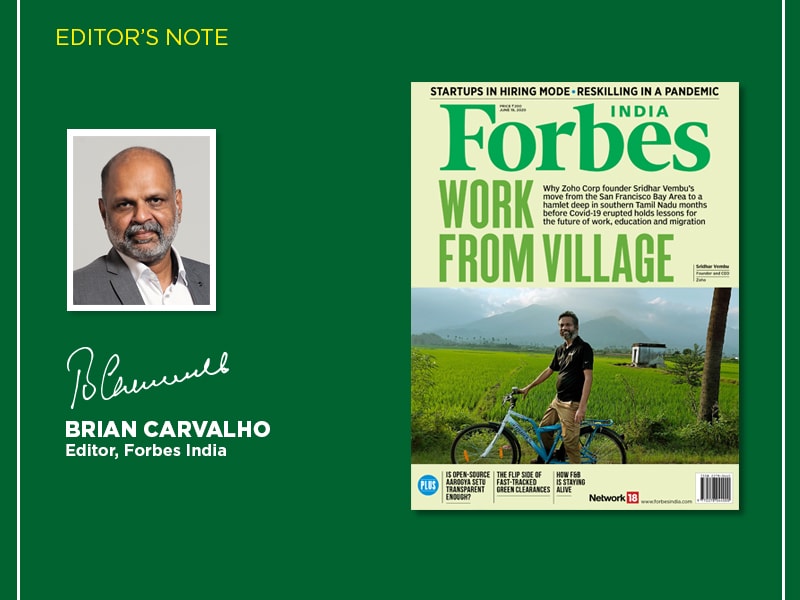

One man who may have an answer is maverick tech entrepreneur Sridhar Vembu. After spending decades in the Bay Area of San Francisco, the 53-year-old founder of software development firm Zoho Corp returned to India last year. In October 2019, months before the Covid-19 crisis erupted, Vembu shifted base to a village deep in southern Tamil Nadu, some 650 km off Chennai; in 2011, Zoho had built its first rural office in the village of Mathalamparai in the Tenkasi district. Vembu’s game plan is to have a substantial portion of his 8,800-strong Indian employee-force working out of such rural offices. As Forbes India’s Naandika Tripathi writes, Vembu is counting on a mix of techies leaving cities for smaller towns and villages, and simultaneously providing relevant tech education (not conventional degrees) to rural youth to make them employable. Currently, 875 graduates of Zoho Schools work at the company. It’s a fascinating tale of a giant shift whose time may have come. Don’t miss ‘Vision from the Village’.

Read Forbes India's latest issue for free, here.

Best,

Brian Carvalho

Editor, Forbes India

Email:Brian.Carvalho@nw18.com

Twitter id:@Brianc_Ed

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)