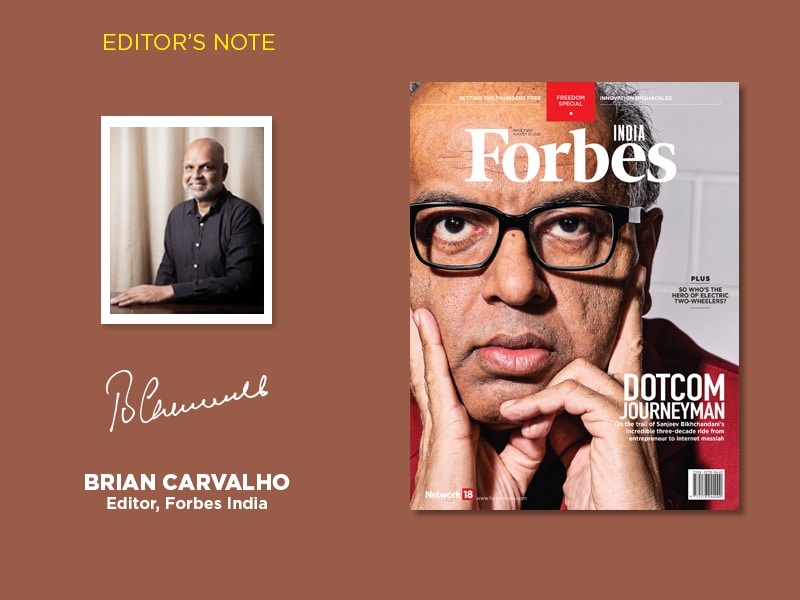

Sanjeev Bikhchandani, a metaphor for freedom in entrepreneurship

From the onset of independence, India is a moving picture of individual action opening new frontiers in industrialisation, innovation and entrepreneurship--and our cover story this week on Sanjeev Bikhchandani is a wonderful metaphor for freedom of entrepreneurship and innovation

In 1962, the champion of free-market capitalism Milton Friedman, with the pioneering tome Capitalism and Freedom, ushered in the idea of how competitive capitalism can pave the way for economic freedom. And that economic freedom is a precondition for political freedom. Inspired by a series of Friedman’s lectures in the mid-’50s, Capitalism and Freedom has lessons for an India that’s debating how far the benefits of economic liberalisation have trickled down 30 years later in a country where millions may have plunged below the poverty line because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Friedman’s book also has lessons for a country whose status dipped from ‘free’ to ‘partly free’, as per the ‘Freedom in the World’ report of 2021 (the government in a statement termed the report “misleading” and incorrect”).

Friedman said there are two ways to benefit from the promise of government without it threatening the idea of freedom. One, by focusing firmly on law and order, enforcing private contracts and fostering competitive markets. And, two, by ensuring government power is dispersed. The pro-centralisation camp may point out that it allows for more effective legislation of programmes that are in the interest of all citizens. Yet, as Friedman wrote, “The great tragedy of the drive to extend the scope of government in general is that it is mostly led by men of good will who will be the first to rue its consequences.”

Friedman acknowledged the role of government in imposing standards in areas like housing, nutrition, schooling (not always the same as education), road construction and sanitation. For instance, he recognised the role of government in imparting a minimum degree of literacy and knowledge, yet felt there has been “an indiscriminate extension of government responsibility”.

Friedman’s short point is that government can never duplicate the variety and diversity of individual action that are vital to open new frontiers. After all, Columbus, Newton, Einstein, Shakespeare, Edison and Ford didn’t break new ground in response to governmental directives.

In India, when nation-building was an imperative post-Independence, the government had a key role in driving industrialisation. However, the ‘Licence Raj’ till the ’90s—when governments regulated production—is a classic instance of heavy-handedness. What is more, many colossal public sector undertakings that were so necessary post-Independence had outlived their utility by the ’90s.