Coronavirus shows why India needs to invest more in mental health care

Isolation and anxiety from Covid-19 is underscoring the fact that India is under-equipped to handle psychological care to the scale that it needs, pandemic or otherwise

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Synthia (name changed), 21, a student of fine arts in Bengaluru, washes her hands at least 100 times on a regular day because of an obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) about maintaining personal hygiene. The progress she had made with counsellors to reduce the tendency was not only undone, but also intensified due to the Covid-19 outbreak. Similarly, Santosh (name changed), 32, a textile entrepreneur in Bengaluru, successfully managed to keep his illness anxiety disorder at bay for a year. He had a tendency to believe that even minor symptoms were signs of severe illnesses. As lockdown measures were being put in place to contain the spread of the pandemic, he found himself frantically reaching out to his psychiatrist, fearing he had contracted the virus.

“He said his heart was racing and he was feeling uneasy in the chest. He also wanted to see a cardiologist. That was an anxiety relapse,” says Vinod Kumar, the psychiatrist who heads MPower - The Centre in Bengaluru, who is treating him and Synthia. “Stress levels are hitting the roof for most of us because all our best-laid plans are out of the window with the 21-day lockdown. The spread of misinformation, fear mongering and general doomsday attitude that many people are carrying not only trigger anxiety, but may also exaggerate symptoms in those with pre-existing mental health conditions.”

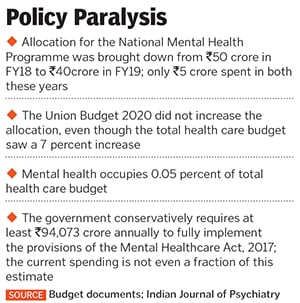

According to the last National Mental Health Survey conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (Nimhans) in 2016, one in 20 people in India suffers from depression, while the treatment gap could be as high as 88 percent. The reasons could range from lack of trained professionals, low awareness or limited access to health care services to stigma around mental health issues.

“Loss of one’s routine in day-to-day life also adds to a sense of unease and increases the risk of brooding,” says Dr Seema Mehrotra, professor of clinical psychology at Nimhans. She says that the pandemic has increased the need for use of remote approaches such as telephonic and online means of providing psychological help. "Clients who have been using mental health services and professional providing psychological services through face-to-face interactions have to get used to new means of professional connect in the current context, while keeping in view ethical guidelines for such services."

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

As of April 1, there were over 1,600 confirmed coronavirus cases in India with the death toll standing at 38. Migrant labourers left jobless by the lockdown were walking thousands of kilometres back to their villages, struggling for food, water and shelter along the way. Health workers, on the other hand, are battling crumbling infrastructure and shortage of protective gear as cases surge.

As of April 1, there were over 1,600 confirmed coronavirus cases in India with the death toll standing at 38. Migrant labourers left jobless by the lockdown were walking thousands of kilometres back to their villages, struggling for food, water and shelter along the way. Health workers, on the other hand, are battling crumbling infrastructure and shortage of protective gear as cases surge.