How the pandemic is reimagining education

With students locked out of schools and colleges, different organisations are reinventing ways to continue the teaching and learning processes

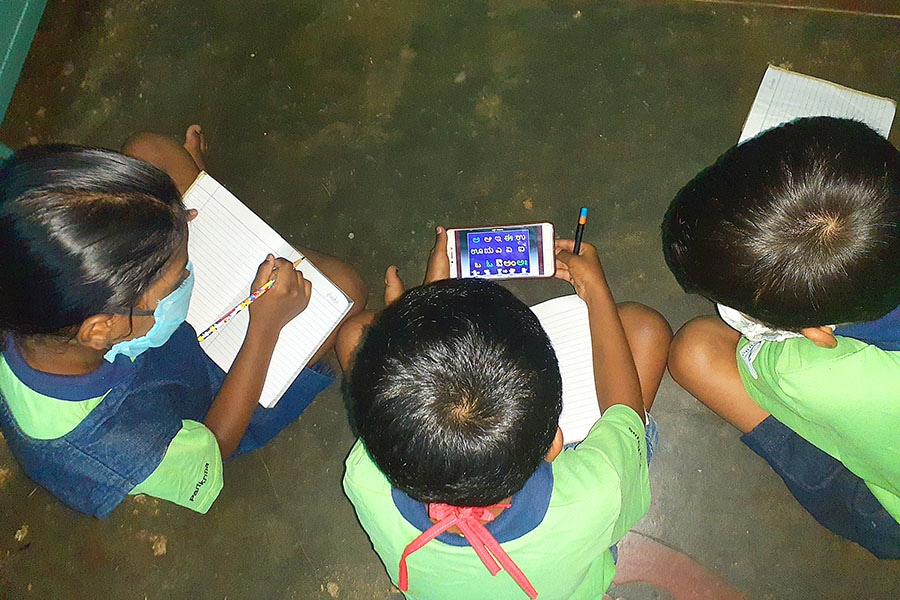

Bengaluru’s Parikrma Humanity Foundation has collected unused smartphones and given them with SIM and data packs to children

Bengaluru’s Parikrma Humanity Foundation has collected unused smartphones and given them with SIM and data packs to childrenImage: Courtesy Parikrma

What 16-year-old Anjali Pandey likes most about attending online classes during the lockdown is the fact that she does not have to drag herself out of bed early morning. Not an early riser, she feels the ability to attend classes at her own pace has made her more productive and efficient. The class 12 student of Government Girls Senior Secondary School No 1, Roop Nagar, Delhi, is part of a pilot online learning programme called Project Aspiration, which was launched in early March by the Delhi government and Career Launcher, to ensure class 12 students continue their education through the lockdown.

“I would prefer these kind of classes over school since I can study at my own pace,” she says, adding, “I don’t think there would be any need for coaching classes at all.” For the project, Career Launcher trained a number of government school teachers on how to conduct classes online. To manage the massive number of attendees, there are assistant teachers who manage online chats and help clear doubts. “Instead of regular 40-minute classes, we started two classes of 1.5 hours each to ensure each child gets enough attention,” says Neha Wahi, chief mentor, capacity building and CLEF AP, of Career Launcher. Every day the platform has about 1.65 lakh students across various subjects, while for students who don’t have access to smartphones or laptops at all times of the day, content is accessible at any time of the day.

Very far from the digitally connected and internet enabled lives of urban students like Pandey, lies the village of Khapri, more than 140 km from the city of Nagpur, in the district of Chandrapur in Maharashtra. On a Tuesday morning at 10.30, families have gathered around the village temple, while maintaining social distancing. In about 15 minutes, the community favourite radio programme, Shalebaherchi Shala (school outside school), is about to be heard on the temple loudspeaker. Every Tuesday and Friday, this morning ritual plays out, as villagers listen, learn and do the activities that the programme talks about.

The coronavirus pandemic, subsequent lockdowns and physical closure of all educational institutions highlights, yet again, the chasm between urban and rural students in their ability to access education. While urban institutes have taken to live and recorded lectures, and portals that are backed by the latest technology, youngsters in villages barely have access to a cellphone.

In the vast swathes of India’s hinterland, where smartphones and internet penetration remain in the realm of impossible aspirations, organisations such as Delhi and Mumbai-based NGO Pratham are reimagining the concept of ‘online’ classes. The radio broadcast that people in Khapri gather to listen is part of an educational programme that it conceptualised, along with the Divisional Commissioner of Nagpur, Education Department and Akashwani Kendra; it comprises “15-minute radio broadcasts, which include educational activities and conversations with children and parents, so that parents understand how best to engage their child in a time like this”, says Smitin Brid, programme director, Early Childhood Education at Pratham Education Foundation (PEF).

The NGO is also sending pre-reading material via SMSes. “Volunteers follow up the radio programme with phone calls to ensure children have understood the concepts. This is a different way of looking at a virtual class,” says Madhav Chavan, co-founder and president, Pratham.

According to Unesco’s estimates, there are close to 300 million learners across all age groups in India who are out of regular schools right now. The organisation is working with 12 state governments, including Haryana, Maharashtra, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi, for content and implementation of remote learning solutions. “Different states have taken different approaches, based on their level of comfort and internet penetration,” says Annapoorni Chandrashekar, Digital Innovations, PEF. So, while Haryana is sending SMS messages to teachers who then send it to parents, along with follow-up phone calls, Himachal Pradesh is working with a WhatsApp and SMS-based model, and Delhi with an interactive voice response (IVR) system.

National broadcasters Doordarshan (DD) and All India Radio (AIR) are also broadcasting educational content via television, radio and YouTube to encourage learning during the lockdown. “The virtual learning through DD and AIR include curriculum-based classes for primary, middle and high school students,” said a press release by the ministry of information and broadcasting.

The digital divide is apparent even within cities, between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. For instance in Bengaluru, India’s hub of technology companies and startups, access to digital devices remains a luxury for many. “We organised a smartphone collection drive to collect old and unused smartphones,” says Shukla Bose, founder and CEO of Bengaluru-based Parikrma Humanity Foundation, a non-profit organisation that runs four schools in the city for children from slums and orphanages. The collected smartphones—with SIM cards and data packs—were then distributed, and could be shared by two or three children.

“Our social workers identified corners in students’ homes where two or three children could sit and study from video recorded lessons sent by their teachers,” says Bose. The video lessons are conducted by teachers who the children already know, and therefore have a connection with. “These relationships with the kids are important,” she adds.

For Kalyani Bhow of Ahmedabad University, the transition to online classes was very smooth

For Kalyani Bhow of Ahmedabad University, the transition to online classes was very smoothImage: Rahul Bhow

*****

On the brighter side of the digital divide is Kalyani Bhow, who is studying for a bachelors in business administration at Ahmedabad University. The transition to online classes was very smooth for her, given that portals for students and faculty members were already in place. “We were sent emails that took us through the new processes, including how to download applications and lists of budget-friendly data packs,” she says. There was close to six weeks of the semester and end-semester exams left when the lockdown was announced. “But now,” she says, “the onus is on me to learn, pay attention and engage in class.”

While attending classes was smooth, assessments changed drastically. “Suddenly I was struggling with deadlines because I had close to 10 assignments in a week,” explains Bhow. The weightage given to semester-end exams was reduced by almost half, with almost 70 percent of assessment depending on application-based assignments. “Now, more than ever, we were not tested on memory, but our ability to apply everything that we have learnt.”

But while Bhow found it easier to adapt to online lessons and assignments, Prutha Pandharkame, 21, studying for a master’s in public policy at National Law School of India University, Bengaluru, still prefers a conventional classroom. Online classes are difficult to pay attention to, given that they can be monotonous, she feels, adding, “Class discussions have become limited. They are defined by how much technology allows them.” Internet connectivity is also a concern, with her college mandate requiring her to be online for 65 to 70 percent of the class duration. “The richness of discussions in a classroom is great. Online classes are a restrictive form of teaching and learning,” she says.

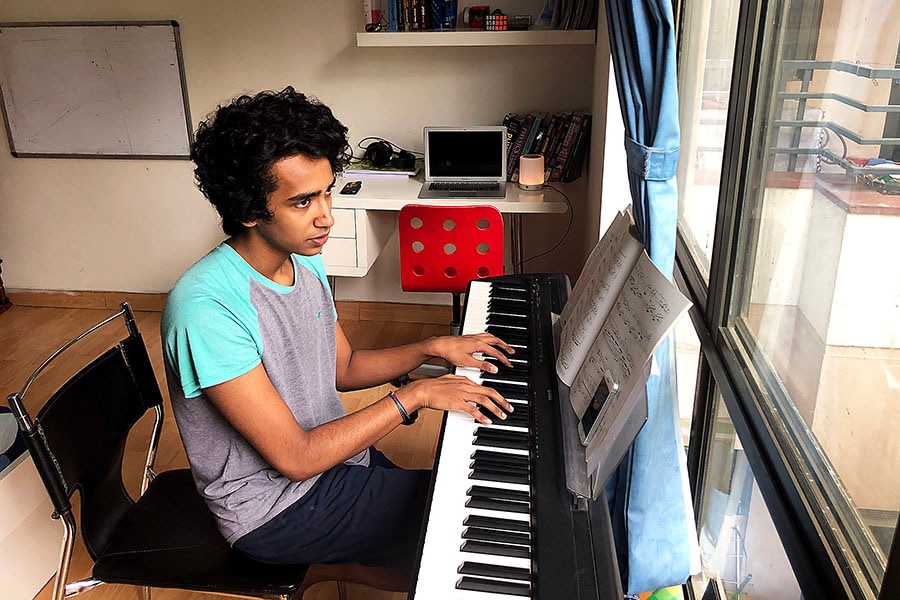

Krish Narayanan is considering deferring his admission to a university in Canada if it decides to conduct classes online

Krish Narayanan is considering deferring his admission to a university in Canada if it decides to conduct classes onlineImage: Bhageerathi Narayanan

Online classes have also raised issues of quality and cost for those who are waiting to gain admission in foreign universities. For instance, Krish Narayanan, 18, who just sat for his class 12 board exams, is wondering if he should defer his admission to a university in Canada to the spring semester next year if classes in the upcoming fall semester are pushed online. “If the classes go online, I will consider deferring a term because the tuition fee is then not worth it,” says Narayanan.

But the immediate worry of the Gurugram resident is something else. “I have accepted the conditional offer at the university in Canada, and need to get 80 percent in my board exams and 90 percent and above in two of the subjects,” he says. “I need to submit my final board results to the university by July. But I’m not sure if we’ll get our results by then.” His only consolation at the moment is, “It’s not just me who has been affected; it’s a global pandemic, I hope universities, both in India and abroad, understand.”

But it’s not just students; educational institutes too are finding themselves in uncharted territory as they conduct various processes entirely online. “We started our teacher trainings for online classes in February as soon as we heard about the coronavirus,” says Monica Sagar, principal, Shiv Nadar School, Gurugram. But she admits that although for primary classes the focus is simply on ensuring a continuation of learning and providing a structure to the day, for higher classes online education cannot replace classroom education and relationships. This is the first time that Sagar has also experienced online admissions: “There were only 25 to 30 new students we were taking in, so interviews were conducted through video calls and online tests. But it was quite bizzare.”

The IITs too have made the shift to online classes. IIT Madras—even earlier it used online learning material in addition classroom teaching—was a first. “We never thought we could complete more than 500 courses online for 6,000 or so students across the country, including far-flung rural areas,” says Bhaskar Ramamurthi, director, IIT Madras. In order to help students, he adds, online evaluations are first being conducted for graduating students who need to take up jobs. For others, exams have been deferred till after the lockdown.

With education at all levels being forced to move online, does it mean teaching and learning will never remain the same again? Anindya Mallick, partner, Deloitte India, believes the use of digital content in addition to classroom teaching is expected to change the student learning experience. “This will imbibe more conceptual learning and create interest in knowledge building, especially for STEM subjects and language.” This experience could lead to a faster adoption of smart classrooms for institutions that can afford it.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)