Indian real estate: A house of cards

The liquidity crisis of 2018 left the real estate sector floundering. Will Covid-19 be the last straw on the sector's back?

It was February 2010. The Indian real estate community had congregated at The Atlantis in Dubai for the annual meet of the Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Association of India (CREDAI). The champagne flowed, people partied, dinners followed at the Burj Khalifa. It was just two years after the global financial crisis and developers thought they were back with a bang. They went on to raise prices, offer fancy loan schemes and build massive malls and commercial buildings. But over the last decade, the sector has crumbled and now the Covid-19 outbreak has left them gasping for air.

One look at promotional text messages from residential real estate developers reveals how prices are moving in the sector across the country. A developer who was offering its 1 BHK at a starting price of ₹ 63 lakh in the central suburbs of Mumbai in January had repriced it to ₹51 lakh in the last week of April. In the times to come, residential prices will fall further, say industry experts.

“We see weakness in new bookings for FY21 due to deferral in purchases, and we also see a higher risk of cancellations in the near term for bookings done in the near past,” says Mohit Agrawal, research analyst, IIFL Institutional Equity Research. He adds, “Our base-case assumptions have seen a 40-60 percent decline in new bookings, including a nearly 10 percent reduction in property prices over FY21, with a gradual recovery over FY23 and beyond.”

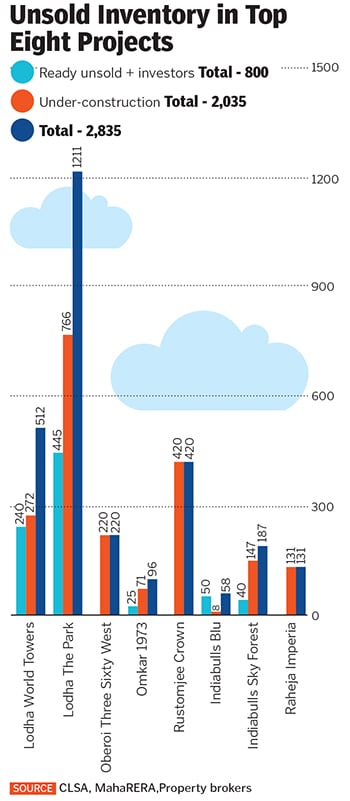

Capital markets and investment group CLSA’s Kunal Lakhan in his report released on May 11, too says that prices in Central Mumbai—Lower Parel and Worli— have seen a drop of 12-15 percent post Covid-19 but prices had been falling even post receiving occupancy certificates as investors had been offloading their inventory holdings. According to the report, just these two micro markets have an overall unsold inventory of nearly 3,000 units worth ₹ 290 billion, which Lakhan believes will take 9-10 years to sell.

“The delay in sales conversion due to the Covid-19 situation is likely to affect business growth plans in the short term. But we do not anticipate major correction in prices given the high input costs,” says Gaurav Sawhney, president, sales and marketing at Piramal Realty, adding that they envisage tactical offers from industry players to boost sales

Arvind Subramanian, chief executive officer at Mahindra Happinest, the affordable housing business of the Mahindra Group, agrees. “The Covid-19 will have a protracted impact on the sector and there will be a fundamental reset in the real estate business,” he says. “While initially there was panic, residential is a durable category and we don’t see that going away. The aspirational value of home ownership remains strong and there will be a deferral of demand, rather than a contraction.”

‘Mahindra Happinest is developing nearly 16 lakh square feet across Chennai and Mumbai, with a growth pipeline in these cities as well as in Pune and Bengaluru. It began construction on some of its sites after the partial lifting of the lockdown on April 20. The real estate arm of Mahindra Group has nearly 1000 labourers across its camps.’

But more than demand side problems, Subramanian is concerned about the immediate supply side challenges that are cropping up across core infrastructure sectors in India. “While we have provided our workers shelter, food and wages, they are getting calls from their families and the mental frame they are in, the moment long-distance trains start they will go back. So the coming three to four months are going to be quite difficult,” he says.

With the country having been under lockdown for nearly two months, lakhs of migrant labourers have been walking back to their homes thousands of kilometres away and it is unlikely they will return anytime soon, which will impact the completion of existing under-construction projects and newer launches.

The cascading effect of the same will be seen by developers in cash flows. Residential is a simple business—the financial closure is usually done in the form of the developer’s equity in the project, a real estate private equity firm financing the project, and the sales to buyers with bookings and sales money received from the customer.

When a buyer buys a house and takes a loan, the bank releases the money to the developer on completion of every floor/other milestones. Which means if a developer is not able to construct on time, it will result in a gap in financial closure.

“The focus in this period is that as soon as construction is permitted, we rejig some of these numbers in terms of asset pricing and also provide for additional working capital so that the construction does not stop and reaches a certain milestone where people will be able to see that the project is moving. It will provide credibility and we will also be in a better position to call for customer money,” says Balaji Raghavan, managing partner and chief investment officer-real estate at IIFL Asset Management.

While lending had been on an upward curve since 2015, the sector found it difficult to raise money and complete projects after the liquidity crisis of 2018. In 2019, bank lenders and NBFCs together lent ₹ 1.27 lakh crore to developers, the lowest in five years.

Now, while the Reserve Bank of India has allowed a moratorium on term loans by banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), experts say the industry has reached a tipping point where lenders have no choice but to see loans being impaired.

The asset covers provided against these developer loans are 1.2x-2x and another 12 months of interest mounting on those loans will create a huge impact on the lending ecosystem. Fund managers say it’s not just about a developer’s ability to pay its finance costs, but in some cases their ability to pay the principal loan amount too.

But the situation is not all bad either, according to both Raghavan and Subramanian, who say that they are seeing some amount of sales happening in branded companies, and developments that are more sustainable and offer better community engagement.

Over the last decade, as the residential sector has faltered, the commercial sector has been a safe haven for global investors betting on rental yields in India.

Indian real estate has seen a heavy inflow of capital through real estate private equity (REPE) firms. According to property consultancy firm Anarock, REPE investments in India between 2005 and 2019 stood at $25.6 billion, of which $16.6 billion or 84 percent came in just the last five years with heavy investments from the likes of Blackstone Group, Brookfield Asset Management, and an international investor like Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), among others.

Most of this capital has floated towards commercial office spaces, retail malls and warehousing facilities across the country. The year 2019, in fact, was the best year for commercial office space in India, with the country being one of the best markets in Asia with a net absorption of 46.5 million sq ft, a jump of 40 percent on a year-on-year basis. With pressure on rentals now, even the crème de la crème of Indian real estate is under pressure for the first time.

“Q2CY20 will be a washout in terms of leases, so if we consider 9-10 million sq ft happens in the first half of the year, can new leases worth another 10 million sq ft happen during July-December?” asks Abhishek Kiran Gupta, chief executive officer of CRE Matrix, a data analytics firm.

Gupta says while individual landlords are ready to sit across the table and negotiate rentals, deals with institutional developers are still a little hard to come by. “Those tenants whose leases are expiring this year are in a better position as it will be difficult to find a new tenant and landlords are more likely to negotiate and offer discounts in the range of 5-20 percent,” Gupta opines.

In a webinar recently, Karan Virwani of WeWork India said it had given 70 percent rebate on rentals in the form of credit to its occupiers, for the period of the lockdown.

However, as far as institutional developers are concerned, rents are unlikely to go down. Global funds expect that supply of commercial space will shrink in the market as banks will not lend and only businesses with a strong balance sheet and deep pockets will continue to build and lease.

“Our occupiers have been able to operate their critical business infrastructure without interruption and understand their obligation to comply with the terms of their leases. Given our marque tenant roster, we have minimal impact on business,” said a spokesperson at Embassy REIT in an emailed response. Embassy has nearly 33 million sq ft of commercial office space and is the only Reit listed in India. In fact, with lower debt on their books, firms like Embassy are left with more room for continuing development and acquisition.

Some global fund managers also argue that most of their tenants are multinational clients for whom rentals constitute only 5-7 percent of overall costs. Effective rents for US companies are already effectively down 10 percent since July last year when dollar to rupee was ₹ 69 as compared to ₹ 76 today.

“Office spaces are largely occupied by MNC companies and they have paid rent. A majority of them understand that force majeure does not apply. The rent collection for April has been more than 90 percent in most of the properties,” says a fund head of a global REPE firm which has deployed over $4 billion in India in acquiring office spaces.

The fund manager adds, “Vacancy is already low in India—especially in markets such as Bangalore and Pune. Hence rents cannot come down.”

While another school of thought says that space requirement per employee might go up due to social distancing norms, that is unlikely given that companies under stress are resorting to layoffs. Besides, large IT firms, one of the biggest occupiers of office space, have been indicating that work from home can become a part of their culture.

One sector that has been worst affected is retail—from mall developers, retailers and cinema multiplex owners to food and beverage owners, the entire spectrum has seen capital turn pariah. A look at consumer spending data also suggests that in Q12020, the spending stood at 4.5 percent as compared to 5 percent in Q12019, so consumer spending had started to wane even before the Covid-19 crisis struck.

Agrawal says, “While mall owners believe that, contractually, rentals are payable by retailers, they have not raised invoices for April and they are looking at engaging with retailers nearer to the opening of malls.”

The real estate fund head quoted above adds, “Retail will take time to stabilise and even after the lockdown opens, they might need 12 months of handholding.”

The problem with mall developers is that they have raised money from banks through lease rental discounting (LRDs) and unless the holding company’s balance sheet is strong enough, there will be defaults, as payments are dependent on retailers paying their rents.

As per pre-COVID-19 Anarock estimates, around 8.4 million sq ft mall space was planned to be completed across the top seven cities in 2020. The planned new completions across the top seven cities might drop 30-50 percent overall in 2020 as there may be a minimal activity in H1 2020, and the second half may also remain fairly muted.

With social distancing becoming the new norm, the Indian real estate sector too seems to be facing social distancing of its own.