Personal finance: Understanding the new mutual fund paradigm

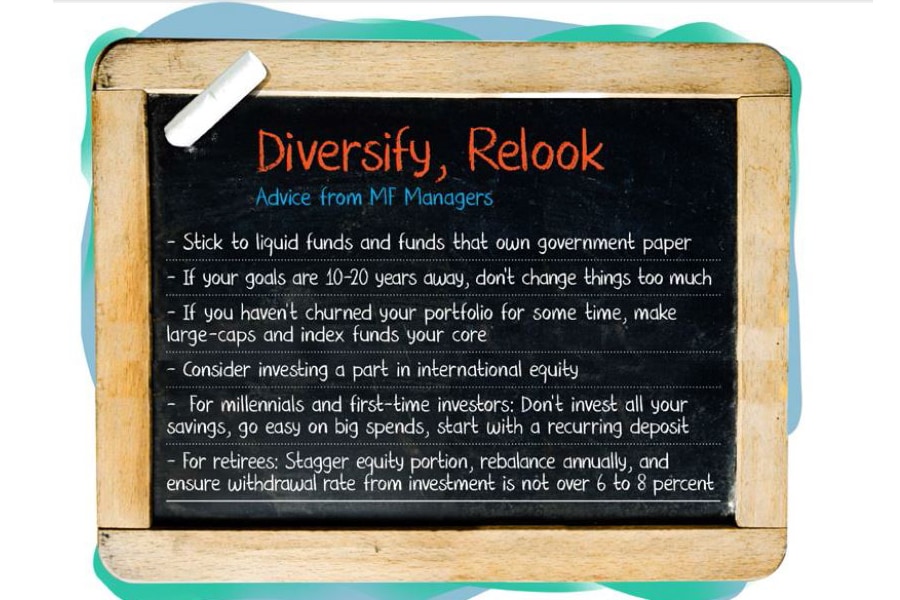

Why the pandemic-induced volatility is a wake-up call to ensure measured and diversified asset allocation, and relook portfolios

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

About five months ago, the founders of Agile Connects, an Internet of Things startup, put the entire corpus they had raised recently for business expansion plans into the Franklin Templeton Ultra Short Bond Fund. But on April 23, Franklin Templeton announced a closure of the fund along with five others on account of liquidity issues in the debt papers they were holding; Agile has been left with no option but to wait. The company, which thought the funds were safe and liquid, finds itself in a hard spot as it has reserves that will only last a couple of months.

“If the money is stuck for the next three years, it impacts our planning ability. Right now we have raised some invoices with our clients to pay salaries and other overheads, but if that money doesn’t come we are looking at a challenging time ahead even to pay salaries,” says Arvind Khungar, chief strategy officer at Agile Connects.

As investors continue to grapple with the effects of the pandemic, and the financial crisis and volatile markets accompanying it, it’s a wake-up call as good as any to ensure measured and diversified asset allocation, and relook portfolios.

After a massive outflow of ₹19,239 crore in April from credit risk funds, the panic seems to have abated for now; the outflow slowed to ₹5,173 crore in May, according to the Association of Mutual Funds in India (Amfi). [Credit-risk funds typically invest in lower-rated securities (below AA-) and gained in popularity because of their potential for double-digit yields]. The data also shows that investors have moved to categories with low credit risk, allocating more to banking and public sector debt, gilt and liquid funds. Flows into debt mutual funds rose to ₹63,665 crore in May from ₹43,431crore in April.

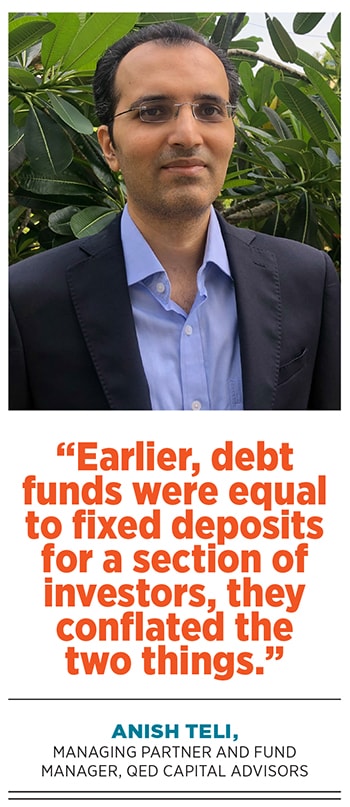

“Earlier, debt funds were equal to fixed deposits for a section of investors, they conflated the two things,” says Anish Teli, managing partner and fund manager at QED Capital Advisors. “Now at least people are asking questions, they know there’s a credit risk, and there is an interest rate risk, and they do not want to get stuck in a credit risk situation.”

The problems with fixed income funds are not new. There have been a few shocks in recent times, starting with the IL&FS crisis in September 2018, followed by mutual fund investments in the papers of Dewan Housing Finance Ltd, Yes Bank Ltd and the Essel Group companies going bad. April saw the peaking of that risk aversion.

“In between a lot of things were done by (market regulator) Sebi, which were good for investors. But, at the same time, they brought all the risk to the forefront, it became visible,” says Dhirendra Kumar, CEO of Value Research, an independent financial advisory firm.

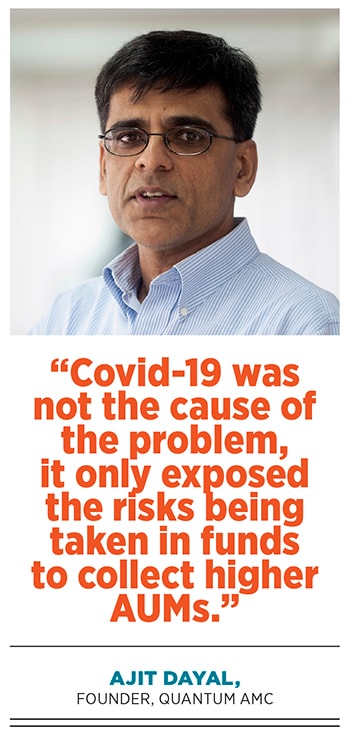

In fact, the risks would have come to the fore even without the Covid-19 crisis, considering the issues in the economy, the banking system and NBFCs—the pandemic simply accelerated the process. “Covid-19 was not the cause of the problem, it exposed the risks being taken in funds to collect higher AUMs (assets under management),” says Ajit Dayal, founder of Quantum Asset Management Company (AMC). AMCs often take risks in credit risk funds to generate high returns, but in the process, dangerous products are created. After the IL&FS shock, says Dayal, some AMCs restructured a few of their products while others, like Franklin, got more aggressive.

In fixed income funds, investors have the option of withdrawing their money anytime, but this might not be possible for all the investments the fund manager has made as there may not be buyers for the debt paper these funds have. Markets for debt paper in India are illiquid except for very high quality government and corporate paper. In cases of such asset-liability mismatch, if a lot of investors turn up, a credit event like the Franklin case occurs. And when investors are unable to take out their money, they also tend to take it out from elsewhere. “Everybody will say, never mind the high returns, let me get my capital back for now,” adds Kumar.

The advice right now is to invest in liquid funds and funds that own government paper. “Until there is an economic recovery, any private sector paper has an inherent risk of going bankrupt. So the only debt fund you should be buying is one that owns government paper,” says Dayal.

Financial planners also think it is a good time for investors to take a hard look at their portfolio depending on their goals, and get rid of any junk they might have collected.

“In 2008, while a lot of people were invested in direct stocks, this time they are there through mutual funds, which is a good thing,” says Anish Teli of QED. However, what may be different this time around is the severity of job losses and salary cuts, and their effect on investing behaviour is yet to play out.

The general advice is not to change things around too much, if you don’t need to. Because for those in the accumulation phase, whose goals are 10 to 20 years away, even if the market outlook remains grim for two years, it doesn’t make much of a difference.

But for those who have not rotated their portfolios in some time, it’s a good time to relook and get into the large cap category and index funds. “And make that the core, and on the satellite part you can still look at maybe middle, small [caps], and then some direct stocks or some sectoral bets,” says Teli.

A third of the investment in equity can also be invested abroad.

Millennials and first-time investors, especially those facing a reduction in income, should use the opportunity to learn not to be impulsive with big spends, and should not waste the crisis by investing all the money they can save. “If you don’t understand where to invest, start with a recurring deposit,” advises Kumar.

It is, however, the retirees, who are dependent on withdrawals from their investments, that are going to have a difficult time especially if they have retired over the last four to five years and have been channelised into a balanced fund or an equity savings fund as well as having invested it in lump sums and risked getting in at a high level.

For a retiree investing into equity and debt, the advice is to stagger the equity portion over a period of time, rebalance annually and ensure that the withdrawal rate from the investment does not exceed 6 to 8 percent. “Most of these people believe that if they’re getting dividends from their investment, their investment is working, but it just might be eating into their capital. You can consume only the real return on your investment, which is return minus inflation,” points out Kumar.

He adds that in the current situation it pays to be cautious considering the outlook for the economy remains grim. With company earnings getting substantially dented, things might not be very rewarding in the next couple of years. “Because at the end of the day, market performance is a function of companies making money and growing,” adds Kumar.

Considering the uncertain economic outlook coupled with job losses, and population displacement due to the pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns, mutual fund managers too are looking at companies that will come out stronger on the other side while reducing their exposure to leveraged companies.

Across portfolios, whether debt or equity, fund managers are looking at low to moderate leverage. “I want to ensure that whenever the upturn comes, my company should be surviving so that I can participate in the upturn. Leverage is lethal and we are moving away from leveraged companies,” says Nilesh Shah, managing director of Kotak AMC.

SBI Mutual Fund, too, is focused on the resilience of companies rather than taking large thematic or sectoral calls. “We are looking at businesses which have the balance sheet, liquidity and capability to survive this crisis. And where we believe managements are taking the right actions to thrive on the other side of the crisis,” says Navneet Munot, chief investment officer at SBI Mutual Fund.

Unlike in a regular economic slowdown, where industries across the board are affected and then slowly come out of it, the current crisis will have some long-term consequences for a few industries —and some might not even make it to the other side or will take a very long time to come out.

Sectors like hospitality, airlines, malls, movie halls belong to the latter category while those in the production sector will bounce back faster. “In the auto sector and personal mobility, the fear factor will play a role at least until the health crisis is resolved and two wheelers and small cars looks interesting,” says Chandresh Kumar Nigam, MD and CEO of Axis AMC. They are also looking at the global trend towards reducing outsourcing dependence from China which might play out some interesting stories, perhaps not in the large cap space but in the middle, small cap space.

With work from home becoming the norm, the commercial real estate sector is up for a tough time at least for a year to a year and a half, which will also affect associated sectors like office security, office stationery and public transportation. However, in the long term, with the global economy under pressure to control costs, large parts of operations might get outsourced and might play out in a manner beneficial to the country.

Changed consumer behaviour in a post-Covid world and how companies adapt to is also a factor affecting allocations. “Discretionary spends might see some pent-up demand in the next three to four months, but incomes will not really support consumption or discretionary spends in a big way, be they travel holidays or white goods,” says Nigam.

“Everything that is luxury will be cut. So every company will have to think about how they can create a shampoo bottle to a sachet model for their products and services. If I am only going to sell shampoo in a bottle, there may not be any takers because that guy’s spending power has come down. But if I convert it into sachets, they will probably keep on buying one sachet every week and I will still have some amount of growth,” points out Shah .

He adds that companies that are unable to make a transition to online will also find it very difficult. “So we are trying to observe change in consumer behaviour and relate it with how our portfolio companies are adapting. If they are not adapting, then it is not worth investing with them because when the upturn comes, when the post-Covid world comes, they will be a misfit over there.”

Fund managers also think there is value in looking at opportunities that are not available in India. “The entire technology and innovation space... there are pockets of that which we do have, what we call as consumer internet businesses, but the Netflixes and Amazons of the world are not listed on the Indian bourses. I think there’s some opportunity for us to start allocating money there,” says Nigam.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)