The race to make a Covid-19 vaccine in India

Companies in India are using diverse technologies to develop a coronavirus vaccine, but even as they race against time, the road to an efficacious solution is neither straight nor short

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurThe timeline is historically short: Create in 18 to 24 months what you usually get five years or more to do. In mid-May, as the number of people testing positive for coronavirus increased to 4.48 million, including 82,000-odd from India, and counting worldwide, scientists have been breaking their backs to find a cure. A powerful treatment that experts say should be at least 95 percent effective against the outbreak and one that could be administered to people across ages, pre-existing health conditions, and geographies. Creating an effective coronavirus vaccine is a tall order, and an urgent one.

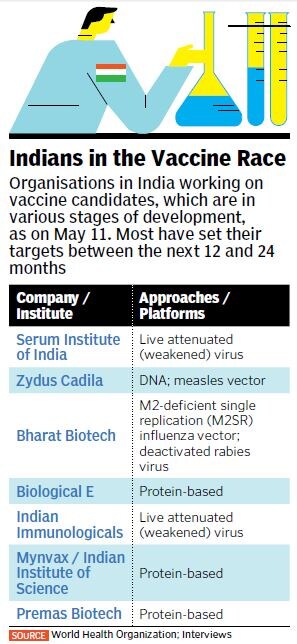

According to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), a foundation that tracks the global Covid-19 R&D landscape, there were at least 115 ongoing vaccine initiatives worldwide as of April 2020, out of which five are in early-stage clinical trials. In India, at least seven companies and research institutions are working on developing a vaccine candidate using different technological platforms and approaches. The CEPI notes that the “global vaccine R&D effort in response to the Covid-19 pandemic is unprecedented in terms of scale and speed”.

A Reuters report published on April 27 notes that historically, just 6 percent of all vaccine candidates end up making it to the market, often after a “years-long process that does not draw big investments until testing shows a product is likely to work”. But in the case of Covid-19, which has infected crores of people and killed lakhs across the world, while crippling the global economy, traditional processes are being sidelined, and governments, non-profits and pharmaceutical companies are investing billions into platforms even with low odds of success.

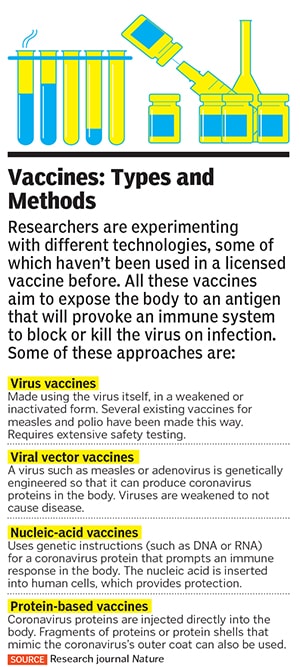

Rakesh Kumar Mishra, director of the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in Hyderabad, says testing different approaches is key to achieving results in highly compressed timelines. At present, he explains, companies in India are using a wide range of methods (see Vaccines: Types and Methods) for vaccine development. This includes using the virus itself in a weakened or inactivated form, using nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) to prompt an immune response, or vaccines made using coronavirus proteins.

Dr Krishna Ella and his team at Bharat Biotech in Hyderabad are working on ‘CoroFlu’, a one-drop nasal vaccine built on a pre-existing flu vaccine

Dr Krishna Ella and his team at Bharat Biotech in Hyderabad are working on ‘CoroFlu’, a one-drop nasal vaccine built on a pre-existing flu vaccineImage: Dr Kaushik Ghosh

For example, the three leading platforms being built in India, which have received funding from the department of biotechnology (DBT), use diverse approaches too. The Pune-based Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine maker by volume, has undertaken mass production of the candidate being developed by the University of Oxford in the UK, which uses the weakened virus platform (see Indians in the Vaccine Race). Pharmaceutical major Zydus Cadila from Ahmedabad is using the virus vector approach, along with developing a DNA platform vaccine. Then there is Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech, which is working on ‘CoroFlu’, a one-drop nasal vaccine built on a pre-existing flu vaccine.

The CCMB, says Mishra, is attempting to grow a large amount of virus in its lab and inactivate it [with heat or chemical processes] so that it can then be used by companies to develop their vaccine candidates. According to him, there is a need to work on multiple vaccine platforms simultaneously because global demand is extremely high and there just might not be enough to go around.

Vaccine manufacturers say authorities have assured speeding up of regulatory processes. This means that if the feedback or permissions from regulators took 2-3 months earlier, it might be reduced to just a week or two now, giving companies significant headway.

“Basically, vaccine manufacturers want to go to Phase I of clinical trials as early as possible,” says Gautham Nadig, co-founder of pharma startup Mynvax, that is developing a protein-based vaccine in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru, where it is incubated.

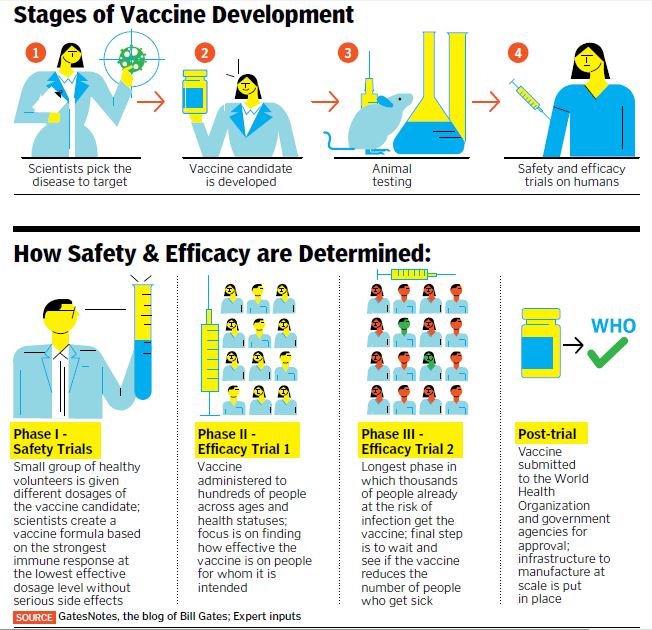

According to him, the real challenge will begin after animal trials, when, as part of clinical testing phases, the vaccine will have to be administered to humans. “Immunising a large group of volunteers to check whether the vaccine is effective will take time, but so long as safety is assured and you have efficacy data from animal testing, it gives a lot of hope.”

Scientists say while regulatory processes can be speeded up, biological aspects—like monitoring the immune response in a heterogenous population, fixing dosage and schedules of vaccine administration, and looking out for possibilities of other long-term adverse reactions to the vaccine—cannot be rushed.

“Without determining all this during clinical trials, going for large-scale vaccination will be risky,” says Dr E Sreekumar, a senior scientist at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology (RGCB) in Kerala. He believes that once animal testing is successful, a realistic timeline for vaccine candidates to reach large-scale clinical use is at least a year. The safety and long-term efficacy of a vaccine is usually tested in a total of three such clinical phases (see How Safety and Efficacy are Determined).

However, given that time is of essence, it is up to the government and monitoring agencies to decide whether they want to be conservative or work out newer, faster, collective methods. “The government is actively working on streamlining and fast-tracking the process while adhering to safety norms. Because the quicker the vaccine is developed, the more beneficial it will be,” says Prabuddha Kundu, co-founder of Premas Biotech in Gurugram, which is developing a yeast-based protein Covid-19 vaccine.  Mynvax Co-founders Raghavan Varadarajan (left) and Gautham Nadig are developing a vaccine in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, where Mynvax is incubated

Mynvax Co-founders Raghavan Varadarajan (left) and Gautham Nadig are developing a vaccine in collaboration with the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, where Mynvax is incubated

Image: Phani Rao

Path to the Vaccine

Many companies in India are building vaccine candidates in partnership with international organisations. The SII will jump-start manufacturing the vaccine developed by the University of Oxford at its own risk while human safety trials are underway whereas the company owned by billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla has partnered with US biotech firm Codagenix and Austrian firm Themis to work on two other platforms. The vaccine candidate being developed by Premas Biotech is licensed out to Akers Biosciences in the US, while the CoroFlu nasal vaccine by Bharat Biotech is in collaboration with virologists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and vaccine maker FluGen in the US. Another Hyderabad-based company, Indian Immunologicals, is developing a vaccine candidate using a live attenuated virus by partnering with Griffith University in Australia.

Microsoft Founder Bill Gates, whose non-profit Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is among the biggest funders of vaccines worldwide, estimates that at least 7 billion doses of coronavirus vaccine (double, in the case of a multi-dose vaccine) need to be manufactured and distributed to satisfy demand across the world. This, he suggests in a post on his blog GatesNotes, will require a “global cooperative effort like the world has never seen”.

Vaccine manufacturers in India say international collaborations foster sharing of knowledge, infrastructure and expertise, and improve quality standards for faster results. Sreekumar of RGCB, however, points to a possible gap in vaccination coverage and immunisation, whereby the developed countries will ensure they use the bulk of the primary supplies while vaccines will be available in India only once their demand is satisfied. “So it would be important for us to have our own capacity too,” he says.

Prabuddha Kundu (centre) and his team at Gurugram-based Premas Biotech are developing a yeast-based protein Covid-19 vaccine

Prabuddha Kundu (centre) and his team at Gurugram-based Premas Biotech are developing a yeast-based protein Covid-19 vaccineImage: Nupur Mehrotra

On May 9, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) announced a collaboration with Bharat Biotech to develop a “fully indigenous vaccine for Covid-19”. An ICMR statement said the virus strain isolated at the National Institute of Virology in Pune has been transferred to Bharat Biotech’s labs to initiate vaccine development.

The Hyderabad-based company is also leading a project sanctioned by the CSIR to develop human monoclonal antibodies, which will block the spread of infection in the body by binding to the virus and making it ineffective. “We are fast-tracking the development process to make the antibodies available within the next six months, and thus improve the treatment efficacy,” says Dr Krishna Ella, chairman and managing director of Bharat Biotech. The company has successfully developed 10 different viral vaccines so far, including for H1N1 (swine flu), rabies, polio and the rotavirus. It has delivered more than 5 billion doses of viral vaccines.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Senior scientist Dr E Sreekumar at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, which has been researching on the virus to aid vaccine development

Senior scientist Dr E Sreekumar at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, which has been researching on the virus to aid vaccine development