U.S. and Pfizer are negotiating deal for more vaccine doses next year

The Trump administration is negotiating a deal to free up supplies of raw materials to help Pfizer produce tens of millions of additional doses of its COVID-19 vaccine for Americans. It could at least partially remedy a looming shortage that the administration itself arguably helped create

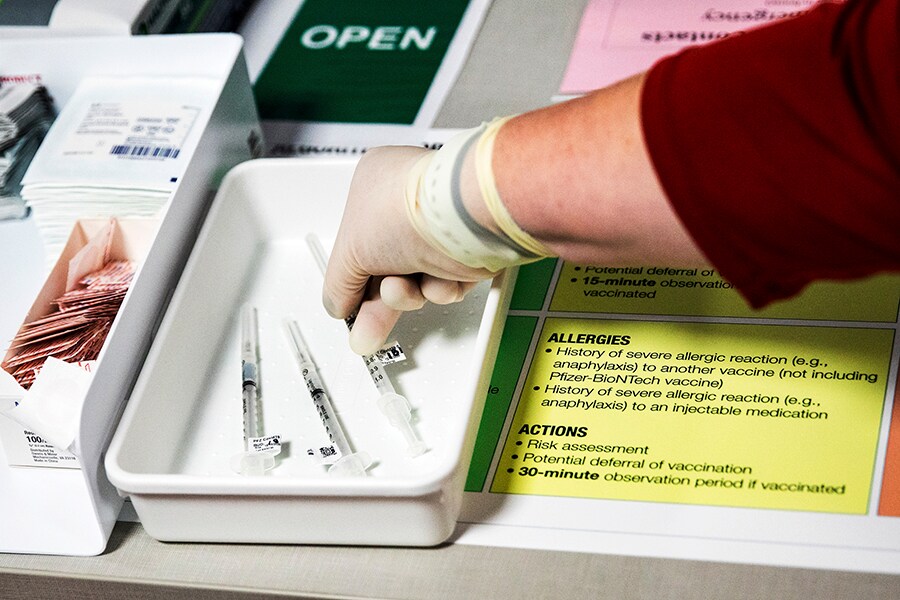

Syringes with Pfizer's coronavirus vaccine, ready for inoculations at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, Dec. 15, 2020. The Trump administration is negotiating a deal to use its power to free up supplies of raw materials to help Pfizer produce tens of millions of additional doses of its COVID-19 vaccine for Americans in the first half of next year, people familiar with the situation said

Syringes with Pfizer's coronavirus vaccine, ready for inoculations at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, Dec. 15, 2020. The Trump administration is negotiating a deal to use its power to free up supplies of raw materials to help Pfizer produce tens of millions of additional doses of its COVID-19 vaccine for Americans in the first half of next year, people familiar with the situation said

Image: Scott McIntyre/The New York Times

The Trump administration is negotiating a deal to use its power to free up supplies of raw materials to help Pfizer produce tens of millions of additional doses of its COVID-19 vaccine for Americans in the first half of next year, people familiar with the situation said.

Should an agreement be struck, it could at least partially remedy a looming shortage that the administration itself arguably helped create by not preordering more doses of the vaccine Pfizer developed with its German partner, BioNTech. Pfizer agreed this summer to provide the United States with 100 million doses by the end of March, enough to inoculate 50 million people since its vaccine requires two shots.

The Pfizer vaccine is one of only two that so far have been proven to work. The administration has locked in only enough doses of the two vaccines — the other, produced by Moderna, is on track to receive emergency authorization from the FDA this week — to cover 150 million people by the end of June, or less than half the nation.

The administration recently asked Pfizer to sell it enough doses to cover an additional 50 million Americans, but Pfizer said it had already found customers around the world for all the doses it can produce until around the middle of next year.

In recent days, however, Pfizer has indicated that it would be able to manufacture more doses if the administration orders the company’s suppliers to prioritize its purchase requests. The two sides are now negotiating a contract under which Pfizer would provide tens of millions more doses between April and the end of June.

©2019 New York Times News Service