Apparel's latest trend: Used clothing

Used clothing is the hottest trend in apparel, and big brands are happy to make the profits—but avoid the headaches—by outsourcing the grimy work to tiny Trove, which looks set to grow big

Trove CEO Andy Ruben says brands have no choice but to get into resale. “Not being in this space is a very risky decision, given the growth and importance of it.”

Trove CEO Andy Ruben says brands have no choice but to get into resale. “Not being in this space is a very risky decision, given the growth and importance of it.”

McNair Evans for Forbes

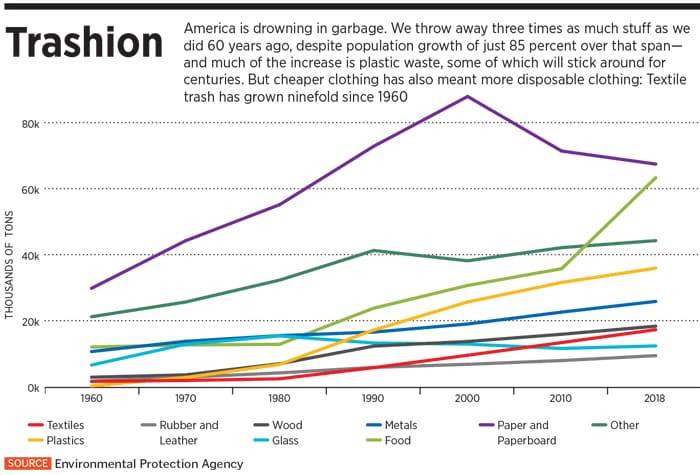

The packages come every day by the hundreds, hauled in on pallets and torn open by a small army of workers. The contents are always a surprise. Somebody’s trash, treated like treasure. An Arc’teryx winter coat that no longer fits. Patagonia boots used to hike the Pacific Crest Trail last summer. A moto jacket from Taylor Stitch bought on a whim. Under the glare of bright lights, the crew notes peccadilloes—discoloration or pilling on a sleeve—and checks for authenticity. Once satisfied, they clean, photograph and prepare an online listing for each item.

The 80,000-square-foot warehouse outside San Francisco is the central nervous system for Trove, the big-brand reseller setting up shop at the crossroads of retail’s tumultuous present and potentially transformative future.

“It’s soup to nuts,” says Andy Ruben, 48, the nine-year-old startup’s co-founder and CEO, whose operation helps companies capitalise on used goods that their customers would ordinarily pawn at vintage shops or dump into landfills. “It’s resale in a box.”

Ruben operates behind the scenes to power resale offerings for Patagonia, REI, Levi’s, Arc’teryx, Taylor Stitch and Eileen Fisher. There’s more to come: The company says it’s in talks with 15 additional brands and is set to double revenue this year from an estimated $20 million in 2020.

Trove handles the messy logistics of taking back merchandise and preparing it for resale, managing the online listings and shipping the merchandise in each brand’s own packaging.

It’s a one-stop shop for retail’s unsexy new trend: Used clothes. Secondhand products represent a $28 billion business that’s expected to more than double to $64 billion by 2024, according to ThredUp, a San Francisco–based online consignment company. It’s also where the next generation of shoppers are: Most Gen Z consumers see no stigma in buying secondhand, and 40 percent have bought used clothing, shoes or accessories, double that of Gen X and Boomers.

If apparel companies’ sudden embrace of used goods sounds like an about-face from an industry that has long promulgated, and profited from, the idea that shoppers must have the latest fashions, that’s right. “It made them nervous until they realised they could get into the business too. They don’t always have to sell new, new, new,” says Dana Thomas, author of Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes.

The trend has even spawned its own marketing-friendly new word: Re-commerce. “In a lot of ways, our re-commerce business checks all the boxes around what we are hoping to achieve, which is providing products to more and more customers while lowering our environmental impact,” says Ken Voeller, who manages second-hand sales for REI, noting that the segment doubled for the recreation cooperative last year—fuelled by customers 10 or 20 years younger than its traditional member base and twice as valuable.

One of them is Kevin Griffen, a 25-year-old legislative intern from Indianapolis. While shopping for Black Friday deals last year, Griffen went to Patagonia’s site hoping for a sale that might make the normally costly items more affordable. What he found was a banner on the homepage urging shoppers to buy used versions of their clothing and gear. He paid $80 for a zip-up blue sweater that costs $140 new. He received it within a week, unblemished by rips, tears or stains.

“It’s nice to contribute to recycling efforts and also spend less money than [on] something that’s new,” Griffen says. Used clothing has been a fast-growing part of the outdoor clothing company’s estimated sales of $800 million, up 40 percent in 2019.

Of course, Trove doesn’t have this space to itself. It’s battling a crowd of online marketplaces that for years cut original manufacturers and retailers out of the action but are now trying to bring them in. ThredUp, which filed confidentially for an IPO in October, has begun running tests with Walmart, Macy’s, the Gap and others in which shoppers can buy or sell used clothing in a limited number of stores or online. Luxury online marketplace The RealReal, which went public in 2019 and moves more than $1 billion in merchandise every year, ran a similar test with Gucci in 2020. Newly public Poshmark has remained hands-off, happy to let its 32 million active users traffic in $15 striped J.Crew tees, $300 handbags from Tory Burch and everything in between.

Trove is far smaller but moving fast. The company tripled the number of items it processed last year to 600,000. It has raised $45 million from sustainability-minded investors such as Prelude Ventures and DBL Partners, as well as Hermès.

Trove employs over 300 people to sift through thousands of one-of-a-kind items and prepare them for resale. Average selling price: $60+

Trove employs over 300 people to sift through thousands of one-of-a-kind items and prepare them for resale. Average selling price: $60+“The distinction between new and used is an old-school distinction that will be erased,” says Ruben, who before Trove was spearheading sustainability issues for Walmart when it was a punching bag for environmentalists.

He had plenty of success, enough to win the company’s top accolade, the Sam M Walton Entrepreneur of the Year award, in 2008, but he began to feel his efforts were futile. Walmart removed 13 percent of the resin from a plastic fork, for instance, but then sold twice as many.

“We were high-fiving and celebrating wins as a company but losing ground as a society,” says Ruben, who left to start Trove (then called Yerdle) in 2012 with Adam Werbach, who was just 23 when he became the Sierra Club’s youngest president in 1996, and Carl Tashian, an early employee at car-sharing company Zipcar. It started as a peer-to-peer marketplace for secondhand items where consumers could list stuff they didn’t want anymore and browse for preowned items. They grew to a couple million users but spent heavily on social-media ads and struggled to get high-quality goods. Ruben noticed customers got most excited when they were able to sort through the junk and locate brand names.

He closed down the marketplace in 2016, ceding the terrain to Poshmark, ThredUp and The RealReal to focus on building a white-label service that would enable brands and retailers to sell used versions of their products themselves. Tashian left in 2015; Werbach, who now leads sustainable shopping at Amazon, left a year later.

Ruben’s first customer was Patagonia, which expanded its “Worn Wear” programme online with Trove in 2017, inviting customers to return used items in exchange for a gift card. It was immediately flooded with inventory, which went straight to a warehouse in California (operated by Trove) and was then listed for sale on a website (built by Trove).

Others followed. Shoppers can now purchase a gently worn quilted coat from Eileen Fisher for $225 online, down from $440 at retail. A pair of used hiking boots from REI goes for $89, almost half the $170 you’d pay new. As of October, shoppers can march into a Levi’s store and earn $30 for decades-old jeans that haven’t fit since college, then put the cash towards a new pair. Margins aren’t bad either, with retailers that have been at it for a year making net profits on used items that are just shy of those for new ones. “In the end, it’s not something you can ignore,” says Flavio Cereda, a retail analyst at Jefferies. “It’s not something you can fight.”

Ruben predicts brands and retailers will quickly dwarf the online marketplaces in resale volume, a bold vision that’s far from a sure thing. Trends, though, are on his side. And reselling is a headache that big companies will happily offload. “We’re no longer having conversations with brands about how important this is,” says Ruben. “We’re having conversations, given its importance, about how to think about this.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)