Can Amazon Conquer India?

Can Amazon become 'the Amazon of India' ?

In any country there are e-commerce firms that want to be the “Amazon” of that country. Ironically it’s also what Amazon wants to be outside the US!

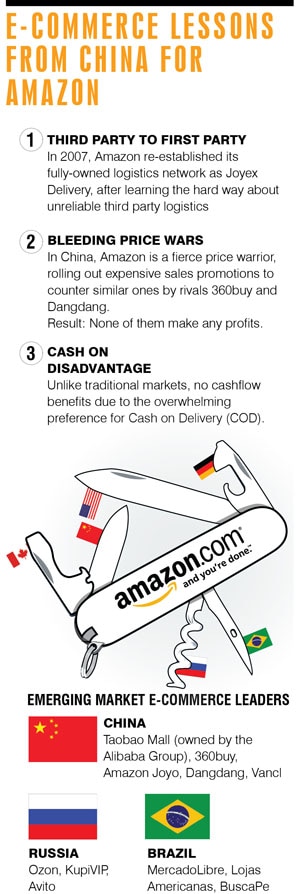

But in three of the largest and fastest growing emerging market e-commerce economies — China, Russia and Brazil — the leading online retailer is not Amazon. It is not even present in Russia and Brazil. “The Amazons” of China, Russia and Brazil are 360buy, Ozon.ru and MercadoLibre, respectively.

Will India be any different?

What Amazon Can Do

There are lots of news and rumours regarding Amazon’s India entry. Amazon did not respond to repeated Forbes India queries on this story. However, multiple media reports and e-commerce entrepreneurs say that Amazon is hiring employees and renting warehouses for an India launch.

That’s surprising because the current retail FDI regulations do not permit Amazon to set up a majority-owned Indian subsidiary. And that is why it needs a local partner.

“There’s not much local knowledge involved in selling standard products like books, mobile phones or home appliances. That comes from categories like food, groceries or apparel,” says Raghav Gupta, a retail consultant with Booz & Company.

Which means Amazon can replicate most of those using its own resources in a relatively short while. “Amazon has global relationships with many multinational vendors, so it may get better prices from them even in India. That is an advantage,” says K. Vaitheeswaran, co-founder and COO of Indiaplaza, at 12 years the oldest e-commerce site in India.

R. Sriram, co-founder of consulting firm Next Practice Retail and ex-CEO of Crossword Bookstores, says, “If Amazon’s goal is to be the dominant online business covering every possible category then what ‘Step One’ is does not matter in the medium or long run. Their customer traffic from India is already four times that of the top online Indian retailer.”

Given that Amazon is not the leader in China, and is not present in Brazil or Russia, the assimilation of local knowledge may not be a trivial matter. So, Amazon will do well to get a local partner on board. And most likely the partner would not be a conventional retailer because none of the large retail groups have been approached by it yet. It will also not be the local e-commerce darling Flipkart because buying a chunk of Flipkart would be very expensive. Flipkart is angling for a valuation of $500 million to $1 billion (CEO Sachin Bansal refused to admit it) on a monthly revenue run-rate of $10 million (which Bansal says will be crossed in September).

“I would almost bet Amazon won’t spend anywhere near a billion dollars on an India acquisition,” says Kartik Hosanagar, an associate professor at the Wharton School of Business. It will most likely be a less expensive e-commerce company.

Emerging Market Lessons

Once the local partnership is in place, Amazon could do with remembering its China experience. In 2004, Joyo was China’s largest e-commerce player before Amazon acquired it. Today, that title belongs to 360buy.com, that started in 2004 and is planning a US IPO worth $4billion to $5 billion, the largest ever. Amazon China and Dangdang, a smaller competitor to Joyo in 2004, which wisely refused a buyout offer from Amazon for a reported $150 million, are both one-third the size of 360buy. The other big player is Taobao Mall, part of the Alibaba Group.

In two of the other leading emerging markets, Russia and Brazil, Amazon is missing in action.

That leaves India as the only large emerging market where Amazon still has a good chance of becoming a market leader. But for that to happen, it’ll have to unlearn a lot.

“It’s not a given that a global player will succeed in Indian e-commerce. E-commerce in the West was built on solid, existing logistics; sourcing too was different. Amazon will need time to figure it out,” says Mukesh Bansal, the founder and CEO of Myntra, the biggest online retailer of apparel in India.

A prime example of that is logistics. One of the reasons Amazon tripped up in China was because it closed Joyo’s internal delivery operations after the acquisition. By the time it re-established it in 2007, it had lost valuable time.

In India and China, unlike the West, third party logistics networks are of low quality. Across cities in Russia, China and Brazil, it is common to see e-commerce couriers on motorcycles, vans or even bicycles, rushing around delivering orders. Many of them even allow competitors to use their delivery networks for a fee, like Ozon.Ru’s 97-city strong O-Courier network in Russia, which is used by 60-odd e-commerce companies. Flipkart too has its own network.

Amazon will need to master Cash on Delivery (CoD) as well. In the West, two out of the three critical flows for an e-commerce company — cash, goods and information — are deftly handled by third party providers, something that Amazon cannot expect in India. In India, like in China and Russia, more than 80 percent of the transactions are CoD.

All of these tend to delay profit breakeven. In China, none of the e-commerce firms reportedly make a profit, in spite of the market estimated to touch nearly $22 billion this year.

India is equally tough because retail margins here are among the lowest in the world.

Impact on Indian Retail

Amazon’s entry will also aggravate tensions for large offline retailers who, till now, have been bumbling along on their e-commerce attempts.

“Aggregators like Amazon and Flipkart worry them, because they can optimise the supply chain across categories to make consumers ‘captive’. No consumer prefers going to Futurebazaar for one category, Shopper’s Stop for the second and Reliance for the third. Instead, they’ll prefer a single site,” says V.V. Preetham, founder and CEO of Quantama, a provider of technology-assisted shopping solutions for offline retailers.

In most cases, retailers are caught in a chicken-and-egg situation:

Online revenues for them are still miniscule, so they don’t devote management bandwidth, capital or resources to it.

Online, they also need to offer lower prices to be competitive. They are conflicted by this, as they are used to much higher prices in their stores to justify real estate and associated costs.

“What they don’t realise is that this conflict is only in their minds, not the consumer’s,” says Vaitheeswaran.

Technology is an Achilles’ heel for most large retailers, till recently powered by staff provided on contract by Infosys or Wipro. Amazon can employ cutting-edge programmers by the thousands, ones who know how to create scalable delivery platforms that deliver millisecond-level responses.

“It’s ironic that businesses on the ground with track records of growth, profitability and customer service are valued lower than their newer online counterparts, most of whom don’t know what profits are. This hampers their ability to raise capital, leaving them with limited options to place their bets,” says Sriram. Existing e-commerce firms ought to be paranoid about Amazon, as it has deep pockets, years of experience and a determination to make things work in India.

In volatile, fast growing markets it can be hard to predict the future. China’s 360buy is today three times Amazon’s size in China, indicating how fast a new entrant can become a leader. With broadband reaching only 2 to 5 percent of Indians, the potential market is much larger than the current one.

“In such cases there is almost no first mover advantage,” says Hosanagar. For Amazon, the Indian Summer will be a long and hard one.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)