David Baazov: The king of online gambling is just 34

David Baazov went from sleeping on Montreal park benches to an $800 million personal fortune with a brazen bet on internet poker. Now he gets to up the ante

Earlier this year, David Baazov walked into the Manhattan offices of the Blackstone Group, the world’s biggest private equity firm, with an outrageous offer. At 33, Baazov was the little-known chief of Amaya, an obscure Montreal company with a loose handful of assets in the gambling industry. But he had big plans. With the backing of Blackstone’s credit division he wanted to stage the $4.9 billion purchase of PokerStars, the world’s biggest online poker company. Operating like he held all the cards, Baazov proposed what would seem to be a crackpot scheme. Despite Amaya’s stock trading at just under $7, he wanted Blackstone and other investors to buy shares at nearly $18 apiece and securities convertible into Amaya stock at about $21.

If a CEO in the history of capitalism had ever managed to sell equity for such a sky-high premium, the top minds at Blackstone’s credit group had never heard of it. They abruptly ended the meeting and threw Baazov out on the street. “We left the building, and my guys were having heart palpitations,” says Baazov.

In the months that followed, Baazov corralled the deeply secretive owners of PokerStars, reluctant bankers and big-shot Wall Street investors—all while driving a hard bargain for himself and other Amaya shareholders. In August, he ended up buying PokerStars by selling approximately $1.7 billion of Amaya stock for about $18 and convertible preferred shares with a conversion price of about $21 per common share. Blackstone’s credit division, known on Wall Street as GSO, invested $1 billion, its biggest-ever financial commitment in a single deal, getting shares at essentially an effective price of some $15 apiece.

With that one transaction, Baazov is now the new king of online gambling, a near-billionaire player in a complex and high-stakes game. The boldness of what Baazov has pulled off is stunning. Nobody—not even his own executives—thought Baazov could get Amaya, a publicly traded company with $150 million in revenues, to buy Rational Group, an Isle of Man powerhouse with $1.1 billion in revenues and a controversial history, in an all-cash deal that included Rational’s PokerStars and Full Tilt Poker.

But Baazov somehow pulled it off, and his stock recently changed hands for $33, returning more than 2,600 percent since he took Amaya public in 2010. Baazov’s 12.5 percent stake in the company is now worth $800 million. “It is an audacious deal that shocked the industry and shocked the people who watch the company,” says Robert Young, a financial analyst at Canaccord Genuity. “They went out and bought one of the crown jewels of online gambling for $4.9 billion, and their valuation was much less than $1 billion.”

Whether or not he ultimately succeeds is still an open question, but Baazov’s story is an untold saga of chutzpah, luck and pure perseverance. “The game of poker itself is like negotiating a transaction,” Baazov told Forbes in his first extensive interview. “This was a really, really big-stakes game.” And it’s only just begun.

For a guy who won about as big as you can win in the deal game, Baazov says he’s not much of a poker player. The son of a construction worker, he was born in Israel, and his Georgian parents moved him to Montreal at the age of one. A math whiz, Baazov was bored at school, and, at 16, told his deeply conservative parents that he was done with it. They kicked him out of the house.

Filled with pride and desperately wanting to start something, Baazov did not back down. For a while he stayed with a friend, but soon found himself sleeping on park benches. After more than two weeks on the streets in cold temperatures, Baazov used his brother’s driver’s licence to rent an apartment. In time he made up with his parents and went on to make some early cash by selling packages of discount coupons for dry cleaning and clothing stores through the mail. Baazov eventually started a computer-reselling outfit in Montreal, renting a tiny office that maybe two people visited in the first five months. “Your conscience runs with your thoughts,” says Baazov. “You are thinking, what am I doing?”

His big break came when he landed a contract to sell computers to Montreal’s public library, expanding his operation into a $20 million computer reseller over the next five years. “He could take apart a computer and put it together with his eyes closed,” says Morden Lazarus, a Montreal lawyer who has known Baazov for years. “Like every Duddy Kravitz in this world, he wanted to be successful and for his family to be proud of him.” At 25, and fearing the direct computer sales model, he abruptly sold the company after losing a bid to Compaq, one of the companies he distributed for, to supply computers to the City of Montreal.

Burned by hardware, Baazov decided in 2005 to get into software, though he wasn’t much more focussed than that. He brought in some developers and to generate revenue they built an electronic poker table that could be sold to casinos and cruise ships. He dubbed the company Amaya, a play on Avaya, the computer networking company where the sister of his chief financial officer worked.

With about $6 million in revenue, Baazov took Amaya public for just under $1 a share in 2010 on the Toronto Venture Exchange, Canada’s penny stock market, raising nearly $5 million. In preparing for his IPO, Baazov, then 29, secured a dinner meeting with former Nato commander and presidential candidate General Wesley Clark, who was a proponent of gambling-generated tax revenue. He returned from the Washington dinner and told his staff that General Clark would join the board. “Did he say he was joining?” his CFO asked him. No, but Baazov was certain he would. “He is the ultimate optimist,” says Marlon Goldstein, Amaya’s general counsel. “His glass is always half full even when it’s fu**ing crumbling.” General Clark signed up and remains on Amaya’s board.

Given this kind of bet-the-house bullishness, it was perhaps inevitable that Baazov would set his sights on the Wild West of online gambling. Because of its close proximity to the Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, which asserts sovereignty and has long hosted online gambling servers for offshore companies, Montreal has been an online gambling hub. Running a tiny, publicly traded company, Baazov bought cheap and out-of-favour assets at steep discounts, like Chartwell Technology and Cryptologic, which provided casino-game software to online operators. Baazov also snapped up Ongame, a maker of online poker software. Critics couldn’t figure out what he was up to, but it was simple: He was building a story and a stock.

In 2012, he purchased Cadillac Jack, a slot machine maker, for $177 million. Now Baazov had cash flow, some $36 million a year. He also had a relationship with Blackstone’s GSO credit division, the largest financial backer of the Cadillac Jack purchase, raising $110 million in debt for the deal. Amaya’s stock soared from $3.50 in November 2012 to more than $7 by the end of 2013.

After buying Cadillac Jack, Baazov told his CFO, Daniel Sebag, that he had his eye on much bigger prey. He wanted to buy Rational Group, the private, secretive owner of PokerStars. “Please do not put even one minute of your time in that,” Sebag told him. It seemed impossible. Rational was not only many times larger than Amaya, it was known to be insanely profitable.

But Baazov smelled opportunity. PokerStars had been essentially founded and run by Isai Scheinberg, a Canadian with Israeli roots, and his son, Mark, who legally owned most of the company. Despite PokerStars’s financial prowess, the owners had run into legal problems for continuing to offer online poker in the US after Congress passed the 2006 Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act. Federal prosecutors shut down PokerStars’s US-facing website in 2011, sued the company and indicted Isai for operating an illegal gambling business. Isai and the company always denied wrongdoing and claimed they were operating legally in the US. The company ended up paying $731 million in a complex settlement that included acquiring its main rival, Full Tilt Poker, but Isai, still under indictment, remained in the Isle of Man, and PokerStars was having trouble getting back into the US after three states—New Jersey, Delaware and Nevada—opened up online poker following the federal crackdown.

When Baazov first floated the idea of buying PokerStars to the Scheinbergs, they didn’t take him seriously. They hardly knew who Baazov was. At one point early on, Baazov travelled to the middle of the Irish Sea to meet with the Scheinbergs, where they told Baazov they were not interested in selling and in any event couldn’t see how he could come up with the money to buy them out. Undaunted, he phone-stalked them throughout the first half of 2013. “I was quite persistent,” says Baazov.

In the summer of 2013, the Scheinbergs decided to call Baazov’s bluff. They told him they would start to negotiate if he could provide a $3 billion commitment letter from a financial firm. This was the kind of news Baazov had been waiting to hear. He asked the Scheinbergs to send over some financial information about the company. The answer he received astonished him: No.

“I got good news and bad news,” Baazov told his troops. “He wants a $3 billion letter, but he is not willing to give us any information.” His small executive group couldn’t see the good news, but Baazov explained it to them. “Any seller who is asking for a $3 billion commitment without providing any financial information whatsoever is a very reclusive seller who will only want to deal with one buyer,” Baazov said. “We will get exclusivity.”

Baazov leaned on his relationship with Blackstone’s GSO division to provide it. Baazov had impressed GSO, consistently hitting the performance figures he had outlined for Blackstone after its GSO division backed his purchase of Cadillac Jack and later refinanced its debt. “He delivered on everything, and we were impressed with that,” says Bennett Goodman, co-founder of Blackstone’s GSO unit. The letterhead impressed the Scheinbergs. In fact, it seemed too good to be true—they asked to confirm with Blackstone themselves.

Baazov caught a break in the fall of 2013, when New Jersey regulators moved to suspend PokerStars’s application for a gaming licence because of Isai Scheinberg’s continued association with the company just as online gambling was launching in the state. PokerStars had worked hard to get into the biggest state to have regulated online gambling, and its owners were frustrated. They were ready to do a deal.

In December 2013, Baazov returned to the Isle of Man, where PokerStars had prepared a management presentation that included, finally, PokerStars’s financial figures and customer data. PokerStars had developed a virtual stranglehold on the online poker market, with 89 million registered users. And since its servers seamlessly made money, raking a small cut of each digitally dealt pot, it was a literal cash machine, making $417 million annually on $1.13 billion in revenues. “Everybody walked away so impressed,” says Baazov. “We knocked off a lot of the misconceptions—it was a phenomenally well-run company.”

By the start of 2014, Amaya and Rational had signed a letter of intent that outlined the $4.9 billion price tag. But even though he had a deal, he had no money. With the same stubbornness that landed him on a frozen park bench in Montreal, he visited Blackstone with his outrageous offer to them. And once again that stubbornness landed him out on the street.

He was undeterred. Baazov continued to press Blackstone, selling them on the huge profits he unveiled once he had his hands on secretive PokerStars’s books. Blackstone was also swayed by other data it found in the due diligence process, like the stickiness of the customer base—60 percent of the revenue was being generated by players who registered at PokerStars between 2001 and 2010. An audit conducted by Blackstone’s cybersecurity chief, which PokerStars passed with flying colours, helped, too. Little by little, Baazov won Blackstone over—agreeing, for instance, to give it warrants that let it buy 11 million common shares of Amaya at just a penny each (he did not, however, give Blackstone a board seat).

By the summer, he finally convinced Blackstone’s GSO to pony up $1 billion and buy Amaya shares for the huge premium he was demanding, while other investors, including BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, also bought a large tranche of shares. For the remaining $2.9 billion, Baazov and Blackstone turned to banks. But there had never been as big a bank loan made against online gambling assets before. At the outset, one of the banks looking at the deal figured there was less than a 10 percent likelihood it would fund the transaction, says one of the people involved.

But the numbers—and the sales pitch—proved irresistible. In the end the banks lent the full amount, and Amaya bought Rational Group. Mark Scheinberg, just turned 40, walked away with a net worth of $4.1 billion, making him richer than Steve Wynn, the man who remade Las Vegas.

And Baazov? He was the real winner. The deal closed on August 1, two days before Baazov’s 34th birthday. With just wit and will, he’d turned his penny-stock public company into a multibillion-dollar online gaming empire, with hardly a cent of his own money invested.

For all the rough negotiating and dealmaking thus far, Baazov is only now confronting his toughest challenges. First, he must somehow run the regulatory gauntlet that ultimately helped cause the Scheinbergs to hit the eject button. Meanwhile, the global online poker industry is in decline. And the US, once the world’s biggest online poker market, remains largely closed for business. Only three states have regulated online gambling, and so far the industry’s revenue resulting from the only meaningful one, New Jersey—about $10 million monthly—have disappointed. Governor Chris Christie had predicted that the state would be reaping more than that in taxes alone.

For the online gambling industry the US remains a tough state-by-state slog with little chance of federal legislation that would bring back online poker’s golden days. Baazov is still having trouble getting PokerStars into New Jersey, while regulation in the biggest prize, California, seems stalled.

Casino billionaire Sheldon Adelson isn’t making things easier. The owner of Las Vegas Sands, the world’s largest casino operator, calls online gambling “immoral” and told Forbes last year that he would “spend whatever it takes” to ban it. He eagerly bashes PokerStars, and its chequered past, whenever he can.

Baazov is more diplomatic. “I think Sheldon is someone I respect and admire based on what he has built,” says Baazov. “I don’t believe that his arguments from a moral perspective hold weight.” The rest of the globe is also fraught with challenges, especially since PokerStars wants to convince regulators in places like New Jersey that it very carefully follows all laws in every jurisdiction. It has already abandoned several so-called grey markets, like Malaysia and Turkey, while Germany and Russia, especially key markets, are in flux.

The Amaya deal even puts PokerStars in a tricky situation in Canada, which has laws that technically ban such sites—something that it has never enforced for offshore sites. But it also never faced an industry giant whose parent company is based in Montreal. Baazov says he kept the Canadian provinces and regulators closely informed about the deal. “Obviously, we had to get a level of comfort before we signed,” he says without offering details.

Baazov is coy about it, but a few provincial lawmakers have suggested that they want to see Canadian provinces get into business with PokerStars in a way that would make online poker a bigger tax revenue generator than it is currently.

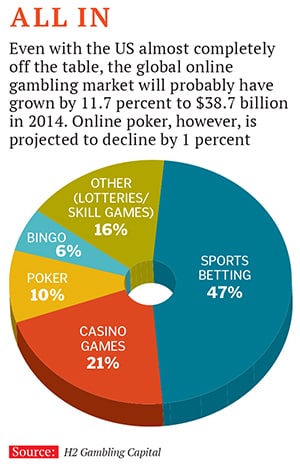

This is the ace up Baazov’s sleeve. PokerStars is the giant of online gambling, and all kinds of jurisdictions and politicians want a piece of its free-spending players. What else can Baazov sell them? The global online gambling industry will reach $38.7 billion this year, according to H2 Gambling Capital—with poker making up only about 10 percent of the total. PokerStars recently launched casino games in Spain and within weeks grabbed double-digit market share. Full Tilt has now launched casino games in much of the world, and 30 percent of its eligible poker players have already given those games a try. Sports betting is next, and Baazov expects it to launch in certain markets by March 2015. His securities filings suggest he wants to eventually offer social gaming, while fantasy sports seems like a natural extension.

Baazov just needs to make sure he doesn’t alienate his core customers. Some online players are already grumbling about recent changes at PokerStars, like higher rake fees of as much as 5 percent that PokerStars gets for hosting games, and currency exchange fees of 2.5 percent. But Baazov is moving forward, cooking up his next deal. He has put Cadillac Jack up for sale and should make a good profit on the asset given the price other slot machine makers have fetched recently. He also just unloaded Amaya’s Ongame unit.

Meanwhile, shares of Amaya continue to streak skyward, up another 17 percent in the past month alone, and Baazov stands ready to jump in other directions.

“My goal is that all of our gaming revenue is sub-50 percent of the company’s revenue,” says Baazov. “We are a consumer-tech-focussed company. We didn’t buy Rational because of gambling; we wanted it badly because it had 89 million consumers. I wouldn’t call them players or gamblers—they are consumers.” Whatever they are, they’ve been a very good bet so far.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)