Guittard: Finding the sweet spot

Despite little name recognition, San Francisco chocolate maker Guittard has managed to survive competition from both the Davids and the Goliaths

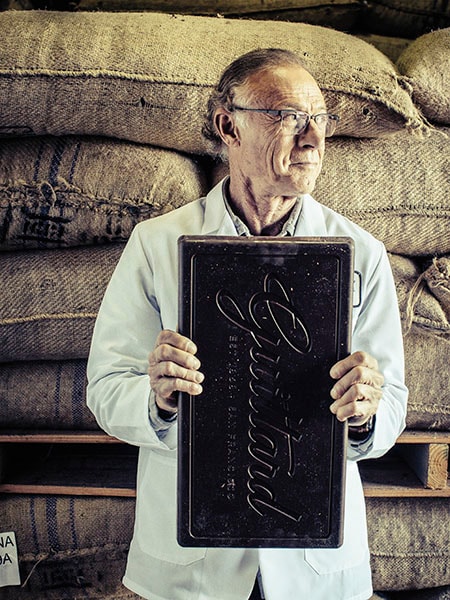

Gary Guittard’s business has built key relationships, like one with a certain Seattle coffee chain

Gary Guittard’s business has built key relationships, like one with a certain Seattle coffee chainImage: Timothy Archibald for Forbes

For many, the arrival of Scharffen Berger’s bean-to-bar chocolate bars some 20 years ago—with their $10 prices, quirky origin stories and artsy wrappers—marked the starting point of the craft movement in American chocolate. For Gary Guittard, president of Guittard Chocolate, Scharffen Berger’s arrival marked something darker. “I smelt something dangerous for us,” Guittard says.

Scharffen Berger, using old world artisanal methods and rare cacao beans, upended an industry that had turned to industrialised manufacturing and cheaper ingredients to reduce costs. Over time, Guittard acknowledges, his company and others had “washed out a lot of the flavour in the beans”. The marketplace responded to the new brand with wild enthusiasm, says Guittard, 71, who concluded, “I needed to make changes in order to survive.”

He spent the next four years experimenting, a process Guittard says nearly did him in. Founded by Gary’s great-grandfather in San Francisco in 1868, E Guittard & Co Chocolates & Cocoa survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the Great Depression and the sudden deaths of Gary’s father and brother, then the company’s president and its designated heir, respectively. The challenge posed by Scharffen Berger was to refine and re-engineer manufacturing techniques to produce the kind of flavour found in artisanal batches but on a larger scale. “I almost lost my mind trying to duplicate that,” he says. “I went back to the way we made chocolate 100 years ago.”

In short, Guittard managed to find a sweet spot by using types of beans the company hadn’t used in decades, old family recipes and some new processing techniques. He could make chocolate with better quality than the big guys, and he could produce that chocolate in quantities that artisanal makers couldn’t match. In the $22.4 billion American chocolate market, Guittard generates more than $100 million in annual revenue, far behind Hershey and Mars, which together make up about three quarters of the US market, but substantially more than small-batch makers like Askinosie, Dandelion and Madécasse (Hershey acquired Scharffen Berger, then generating an estimated $10 million, for a reported $50 million in 2005). Today, Gary says, the company is profitable but chocolate-making remains capital-intensive, and he ploughs an average of 30 percent of profits back into the business each year.

Guittard is the biggest American chocolate company most people have never heard of. It has never established a large retail presence, mostly to avoid competing with core customers like See’s Candies, the iconic California confectioner owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. Guittard began working with See’s, its biggest customer, in the 1930s, supplying it first with dark chocolate and then picking up its milk chocolate business four decades later when Nestlé, See’s original supplier, began selling branded truffles that competed with See’s. “We work very closely with them,” says Brad Kinstler, See’s CEO. “Our particular chocolate that they produce is critical to our flavour. We have special requirements, and they are able to meet our specifications to a T.”

Other clients of Guittard’s bars, chips, wafers, sweet-ground chocolate and cocoa powder include Williams-Sonoma, Baskin-Robbins and scores of bakeries, candy makers and chefs—from Thomas Keller to Jacques Torres. Shake Shack puts Guittard in its chocolate frozen custard, and Wolfgang Puck has used it to make his miniature Oscars for the post-Academy Awards Governor’s Ball. Two years ago, when the restaurant Untitled opened at the Whitney Museum, Grub Street dubbed its Guittard-based triple chocolate cookie New York’s finest. “I like to say, you don’t know how much Guittard you’ve consumed,” says Amy Guittard, 35, Gary’s daughter and the director of marketing.

Guittard began as many ventures do, with aspirations that shifted dramatically. Gary’s great-grandfather Etienne Guittard left his home in Tournus, France, for San Francisco’s Barbary Coast, hoping to strike it rich in the Gold Rush. When he found that wealthy miners would pay handsomely for his chocolates, he changed course. Similarly, Gary never planned to work at Guittard, where his older brother Jay was expected to take over. Passionate about the outdoors and adventure sports, Gary went to college in Colorado and then worked in advertising in San Francisco. In 1973, he returned to the fold, “hat in my hand”, after being laid off. His father, Horace, told him to work elsewhere and develop a skill, and he landed a job as a food broker, introducing new products to grocery stores. Two years later, he joined Guittard, sharing an office with his father and brother, and focussed on expanding sales of consumer products, such as the home-baking line.

When our customers are successful, we are successful. We grow with them.

And then in 1989, after his father, 76, and brother, 46, died within six months of each other, his father of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and his brother of a heart attack, Gary took over the company. The loss was devastating personally, but he says he was ready: “I had a vision; I felt pretty confident. I just focussed on the things that needed to be done and what came next. There wasn’t any kind of ‘aha’ moment or ‘Oh God’ or ‘Oh boy’. There was just the fact and reality that this is the way it is.”

The family’s business had always been based on doing what it takes to build relationships. When sugar prices quadrupled in the 1970s, Gary went to each of his clients and asked them to renegotiate their contracts. The exercise taught him not only who his friends were but also an important lesson: “Those that renegotiated stayed in business. Most of the ones that didn’t don’t exist today.”

In the 1950s, when See’s wanted its chocolate delivered in liquid form, Guittard began sending tankers of melted chocolate directly to the company. This summer, after Guittard missed a delivery date, it took a $11,000 hit to fly 2,000 pounds of chocolate to the Honolulu Cookie Co. Mark Spini, vice president of sales, who’s been with Guittard for 31 years, says, “We understand we’re dealing with entrepreneurs growing their businesses. We were once like that too.”

In the 1970s, a Palo Alto housewife named Debbi stopped by regularly as she experimented with a chocolate chip cookie recipe. Eventually, she launched Mrs Fields Cookies. Around the same time, a friend of Gary’s, working at a fledgling coffee roaster in Seattle, called him seeking help to develop mocha for hot chocolate; Starbucks remains a customer today. “When our customers are successful, we are successful,” says Clark Guittard, 45, Gary’s nephew and director of international sales. “We grow with them.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X