How Kazuhiro Tsuga is saving Panasonic

Four years ago, Kazuhiro Tsuga embarked on one of Japan Inc's most radical overhauls. But he's not done yet turning around the consumer-electronics giant

When you think of Panasonic, you probably think of televisions. After all, the TV set made Panasonic a household name from Singapore to San Francisco and built the Japanese electronics company into one of the industry’s global players.

But for Panasonic President Kazuhiro Tsuga, that was exactly the problem. By the time he took the helm in 2012, Panasonic had seen its market presence wither, outmanoeuvred by South Korean rivals Samsung and LG. Worse yet, the company had bet on the wrong horse. It invested heavily in plasma flat-panel technology, which uses electrically charged gases to create images on a screen, but consumers preferred its lighter, durable rival, liquid crystal display (LCD) TVs.

Panasonic’s executives refused to concede defeat. Engineers in the TV business pointed out that plasma produced a higher-quality picture than LCD and remained stubborn champions of the technology. “Our TV guys really hated big-screen LCD TVs,” says Tsuga. Panasonic committed the cardinal sin of business: Ignoring the verdict of the marketplace.

Tsuga knew it was time to repent—plasma had to go. He finally cracked the fierce internal resistance by telling the truth: Previous top executives had hid the severity of the TV operation’s problems from much of the staff, but he opened the books. “Only a few members of the management team knew how deep the loss was [at the TV operation],” he explains. “What I did was tell them, ‘This is the loss, a huge loss’. I showed them the losses in detail at every stage. Once it’s visible to them, people don’t want to continue to make losses.”

Tsuga had already started the shift away from plasma after he became chief of the consumer-electronics unit in 2011. Then in October 2013, the company finally announced that it would close down the entire operation. Its final plasma plant in Japan was shuttered a few months later. The rest of the TV business has been downsized as well. The company no longer sells TVs in the US and has a minimal presence in China. Panasonic sold only 7.9 million TVs in the year ended March 31; it sold more than twice as many in fiscal 2010. However, for the first time in eight years, the TV business posted a profit.

Tsuga’s gut-wrenching gutting of the TV business was the most symbolic and dramatic of the many reforms he has wrought to save one of Japan’s oldest companies (in two years it celebrates its 100th anniversary). Engineering one of the most unexpected turnarounds in the history of Japan Inc, he ditched other beloved but money-losing operations and reorganised Panasonic’s myriad businesses, which make everything from lights to car batteries to washing machines. Meanwhile, he’s refocussed investment on more promising businesses—from electronics for automobiles to data-storage devices to airplane-entertainment systems—while attempting to provide more services to customers alongside its manufactured hardware. Says Joseph Taylor, chief executive of Panasonic’s North American unit and a 33-year company veteran: “If you look at what he did in his short tenure, it is remarkable.”

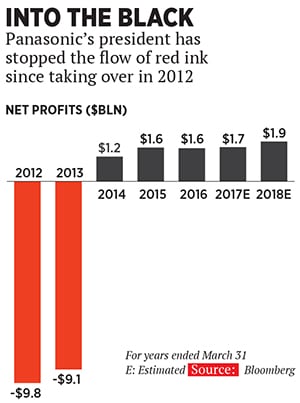

The numbers speak for themselves. Just before Tsuga became president, the Osaka-based company had announced a staggering $9.8 billion net loss for the past year. In the 2016 fiscal year, the company notched a $1.6 billion net profit on sales of $63 billion—its third profitable year in a row. Compare that performance with Panasonic’s stumbling Japanese competitors. Sony has posted losses in four of the last six years. Sharp was acquired earlier this year by Taiwan iPhone assembler Foxconn after suffering huge losses and requiring a bailout by Japanese banks. Toshiba announced a $4.3 billion loss in its last fiscal year, on top of an embarrassing accounting scandal. Panasonic now ranks at No 245 among the world’s biggest companies on Forbes’s annual Global 2000 list, down from No 89 in 2009 but up from No 553 last year.

The knock against Japanese executives is that they are too bound by tradition to adapt to a rapidly changing environment. Instead of plunging into new businesses or adapting to new markets, they cling to old ones in which they are no longer competitive—as Panasonic had done with TVs. Endemic secrecy prevents staffers from speaking their minds or sharing information across departments, stifling new initiatives. Most top Japanese managers spend their entire careers at their companies, making them resistant to changing them.

At first glance, Tsuga, 59, seems like he would be one of these risk-averse old timers. He joined Panasonic as a college recruit and has worked nowhere else in his 37-year career. Stuffed into the standard dark suit of the Japanese executive, the R&D engineer could pass for any ordinary salaryman slaving away in the office towers of Tokyo. An aggressive outsider, such as Carlos Ghosn at carmaker Nissan, has a better chance of compelling a big, bureaucratic Japanese corporation to reform.

Yet Tsuga proved just the right man at the right time. “The change may not have happened if Mr Tsuga didn’t take the role” of president, says Yasuji Enokido, a senior managing director at Panasonic. “He has a very clear and unprejudiced mind about where the market is going, where our business should really go.”

In that way, what Tsuga has accomplished at Panasonic could be a guide for rescuing the rest of Japan Inc. “In terms of decision making, Sony as well as other companies can look at what Panasonic did,” says Shelley Jang, a corporate analyst in Seoul at rating agency Fitch.

Many of those decisions were propelled by sheer necessity. Tsuga, like most other executives at the company, had been under the impression that Panasonic was just fine, save for a couple rotten businesses. But upon being named president, he got his first comprehensive look at the entire company’s financial state, and what he discovered startled him. “It was terrible. It was terrible,” he says. “More than that, it was very difficult to see what was wrong, because we had so many businesses.”

Tsuga realised he needed help—and fast. He turned to Tetsuro Homma, a colleague at the consumer-electronics unit. Homma, 54, was managing the unit’s planning division from an office on the outskirts of Osaka. He received a call from the new boss summoning him to the headquarters.

Over the next 90 days, the two laid the foundation for Panasonic’s revival. Homma spent long hours dissecting the finances of Panasonic’s 88 divisions, separating the strong from the weak. For inspiration he turned to IBM’s turnaround artist, Louis Gerstner, whose book, Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?, he read three times, underlining key passages in red. In the end, Homma and Tsuga discovered that a full third of the business lines were losing money. “We understood we had a lot of issues we had to resolve in a very short time,” says Homma. “We had to change direction more drastically.”

Since not just TVs but many of the company’s trademark products were also struggling, Tsuga realised that Panasonic had to pivot away from consumer electronics in order to survive. It had to remake its entire DNA. “I said we are the loser in the area of digital consumer products,” he recalls. “First I had to say we would no longer pursue such [businesses]. That was the beginning.”

Tsuga and Homma visited the business units one by one. Managers in charge of money-losing operations were given a mandate: Shape up. Tsuga regularly reveals the financial position of every division so that its managers can see how they are performing compared with their peers. “Every quarter—who is making money, who is losing money,” says Homma. “I think this kind of way we can realise serious financial discipline.”

Many businesses didn’t make the cut. In 2013, Panasonic agreed to merge its system-chip operation with Fujitsu’s and sell 80 percent of its health care business to private equity firm KKR for $1.7 billion. It stopped making smartphones, optical disks and circuit boards, and offloaded businesses in IT services and logistics. By the time all of the merging, selling and closing was done, the number of business divisions within the company had been reduced by nearly 60 percent, to 37. Those were further bundled into four main units, each topped by a senior manager. “Making everything simpler is my policy,” says Tsuga.

He applied that principle to his own office as well. The staff at the headquarters—a gated compound of squat, low-rise buildings made distinct only by a statue of American inventor Thomas Edison—had swollen to 7,000 employees. Tsuga saw the headquarters as a bloated impediment to efficiency, where deskbound paper-pushers clogged decision making. So he reassigned nearly all of the staff to the company’s operating units. Today a mere 130 employees remain on his staff. “If the team becomes small, then we can change, go [ahead] quickly, change quickly,” he explains.

None of these changes endeared Tsuga and his top executives to the staff. “All employees saw me as one of the devils,” says Homma. Nor did the market always appreciate their strategy. With great bitterness Homma recalls one day in October 2012 when the company announced another massive loss and some of its restructuring plans: “The reaction was not so happy. I can’t forget one analyst said, ‘Homma-san, this kind of mid-term plan even a high school student can make’.” He calls the day “a nightmare.”

Tsuga is pouring resources into sectors where he believes Panasonic has strong potential. The company, which already provides the batteries that power Tesla cars, pledged in January to invest $1.6 billion in Elon Musk’s “Gigafactory” battery-making operation in the US state of Nevada. To expand its buoyant supermarket refrigeration business into the US, he agreed in December to acquire Missouri-based Hussmann Corp, which makes refrigerator and freezer displays, for $1.5 billion. Later this year, the company will start selling storage devices developed with Facebook to hold large amounts of old data for long periods, with what Panasonic calls “freeze-ray” technology.

Tsuga is also hoping to combine technology and expertise from Panasonic’s wide-ranging product lines to provide specialised services to businesses. Last year the company, already a major provider of cash registers to fast-food outlets, began offering systems with 360-degree cameras and facial recognition software to help the chains’ marketers identify and target certain types of customers. Now the company is working with Hussmann to develop inventory-control systems to mesh with their supermarket refrigerators. “We are very good at technology. We have very good manufacturing skills,” says Tsuga. “What is missing is trying to utilise IT technology together.”

Close to home, Panasonic is trying to better capitalise on the still-expanding markets in Asia. Homma, now in charge of Panasonic’s appliance and TV operations, admits that the company was slow to wake up to the burgeoning spending power on Japan’s doorstep. “Unfortunately we didn’t adapt or understand very well the changing way of consumption of Chinese and Asian people,” he says. Now Panasonic is playing catch-up by introducing pricier, more specialised products to Chinese shoppers, often with greater input from R&D engineers based in the country, from stylish glass-door refrigerators to germ-killing air conditioners to special steam ovens.

Meanwhile, management continues to tinker with new ideas, thanks to Tsuga’s more open style of management. “Just like at any other company in Japan, sometimes it was hard to speak your mind,” says company executive Enokido. “Mr Tsuga has created an atmosphere where we can speak honestly. There are no taboos anymore.” To make his point, Enokido tells of a management meeting two years ago at which one executive made a startling proposal to eliminate the company’s annual business plan. In the past, the plan had been a major preoccupation of management and developing it a time-consuming horse-trading process. Now the company devises a general plan as a guide but doesn’t measure the firm’s performance against it. The idea was to “let all of our divisions focus on growth rather than negotiating what the business plan should be,” he says.

Tsuga has brought Panasonic a long way, but for its turnaround to be a lasting success, the unlikeliest of change agents must keep that change coming. His executives don’t doubt that he will. “We are on the road to where we need to be, but we are not there,” says Taylor, the US CEO. “I wouldn’t say that he is done yet.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)