Howard Schultz: The president of coffee nation

Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz doesn't want to run for the White House. But, buoyed by his company's surging performance, the billionaire wants to use his caffeinated perch to change American discourse

What does Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz keep in his pockets? Two keys stand out. One unlocks the most lavish Starbucks store in the world: The 15,000-square-feet Roastery. Situated in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighbourhood, it combines an upscale cafe with whirring conveyor belts that ferry packages of freshly roasted coffee before admiring customers. Let Nike have Niketown; Schultz has created a Willy Wonka-style celebration of coffee.

The other key reveals something deeper. It opens the shabby little store on the Seattle waterfront where Starbucks got its start. It’s always 1971 there, with the same rough-hewn bins and counters that defined the brand in the days of the Vietnam War. Nobody has ever modernised the place. “I go there at 4:15 am sometimes, just by myself,” the 62-year-old Schultz tells me. “It’s the right place whenever I need centring.”

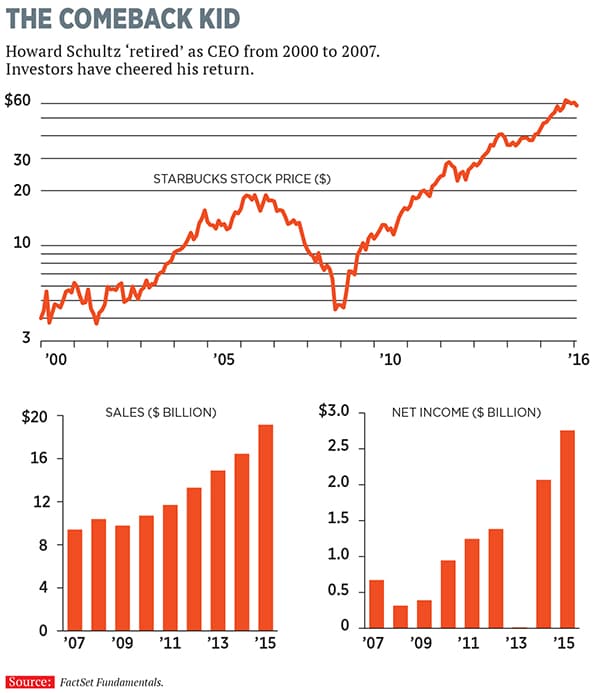

Centring? The last we checked, the willingness of billionaire CEOs to recentre themselves was hovering around zero. But that’s Schultz: Always the underdog, always blending the personal with the profitable. Since taking charge of Starbucks in the 1980s, he has turned a regional coffee company into one of the world’s top brands. Sales topped $19 billion in 2015, thanks to Starbucks’ ability to provide food and coffee along with a feel-good environment where friends meet, students do their homework and romances come of age. By delivering what he calls “performance through the lens of humanity,” Schultz has amassed a fortune of nearly $3 billion. Yet in any sustained conversation, he keeps going back to when he was a nobody.

“I’m still this kid from Brooklyn who wanted to fight his way out,” Schultz says. He grew up in the 1960s in subsidised housing, steeped in the anxieties of a father who suffered workplace injuries and couldn’t hold a job. “I didn’t go to an Ivy League school,” Schultz reminds me. “I didn’t go to business school.” Instead of resenting those early deprivations, he treasures them. Schultz has discovered that America—and, in fact, the whole world—loves an up-from-hardship story. His candour about his beginnings in the gritty Canarsie section helps him strike a rapport with everyone from other chief executives to young black and Latino adults trying to find their first jobs. “Even though I don’t have the same colour of skin,” Schultz explains, “I was one of those kids. I could have today been one of those kids.”

It’s a classic American story, one that forced Schultz to bat down rumours last year that he was going to run for President.

On paper, this self-made tycoon compares favourably to a certain bombastic billionaire springboarded with Daddy’s money. But Schultz wasn’t at all interested in the campaign, in part because, while the 2016 presidential contenders debase themselves during this circus-like primary, Schultz already has a caffeinated bully pulpit from which to steer discourse—and Starbucks’ stunning financial performance affords him pretty much unbridled authority to use it.

More than anything, Schultz wants to become America’s conciliator-in-chief. He’s troubled by the angry tone in politics and everyday discourse, which makes him think that, as a country, we’ve “lost our conscience”.

Searching for inspiration, he’s travelled everywhere from veterans’ hospitals to an Indian ashram in the past year, asking people to share their stories and their beliefs.

Now he wants Starbucks to be the place where people can get excited about voting again, where people can courteously discuss tough issues such as gun rights and race relations—and where “we can elevate citizenship and humanity”.

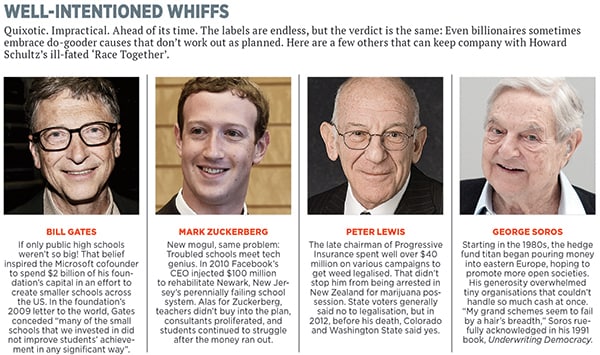

It all sounds lovely, but last March Schultz’s crusade blew up in his face. Everything started smoothly when the Starbucks boss began asking employees in late 2014 about America’s race relations. He was jolted by the upheaval in Ferguson, Missouri, after a white policeman was exonerated in the fatal shooting of an unarmed black teen. His employees were, too. Their private conversations were raw, heartfelt and cathartic. Baristas and store managers burst into tears, talking about ugly moments they had seen. People hugged. Everyone wished that America could overcome its past. Schultz was so moved that he decided to relaunch these conversations in 7,000 Starbucks stores. Baristas were encouraged to write ‘Race Together’ on millions of patrons’ coffee cups. Then, somehow, good things would result.

What unfolded was a national embarrassment. Hectic morning-coffee lines, full of strangers, proved far chillier than a staff meeting with time for hugs. Baristas felt hurled into an edgy new role without any training. Patrons found the gesture bewildering. After this awkward start many baristas put their pens in hiding. Starbucks ended the initiative after a week. (The company says that was always the plan.)

Undeterred, the Seattle coffee king’s ambitions remain as big as ever, with Schultz targeting death-penalty injustices, chronic unemployment, veterans’ needs and the college aspirations of his baristas. Watching Schultz’s crusades in the wake of the race debacle is akin to seeing a sword-swallower at a carnival. Each project generates its own rush of excitement. Each is tinged by a thrilling, terrifying sense that it could all go horribly wrong in an instant.

A few weeks ago Schultz and I ended up at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, in an empty theatre, sipping Starbucks’ Aged Sumatra from paper cups. Schultz was collecting his thoughts, minutes before going onstage to fire up 300 of his employees about his favourite topic: What’s wrong in society and how his company could be a force for good. “We’ve got this big idea,” he told me, in a voice that mixed eagerness and hesitation. “It’s like a piece of clay, but it’s not yet shaped. I’m going to ask people for their help.”

Bounding onto the Brooklyn stage, Schultz began by ticking off issues that concerned him: Death benefits for soldiers killed in Iraq or Afghanistan, gun safety and the 2016 presidential election. “We’re not just here to raise the stock price,” he declared. “What can we do to use our strength for social good?”

Over the next 90 minutes 34 store managers and baristas took the microphone to share their ideas and concerns. As with most voters, they were less interested in policy theories—save a few that talked about their own volunteer work in local schools—and much more into the gritty realities of their daily lives. We get a lot of homeless people in our stores… Can we get more security?… Can we get more training for the baristas?… Could there be a child-care option?

If Schultz was disappointed, he didn’t let on. “That’s a great idea,” he told several questioners. “We’re working on it,” he reassured others. When one part-time employee wanted to know why he wasn’t getting much paid vacation time, Schultz started to lob the question toward a human-relations specialist in the audience—and then caught himself in midsentence. “You know what?” Schultz declared. “You’ve been here 16 years. You deserve a vacation. We’re going to get you one.” The room burst into applause. Schultz came over to give the barista a hug, and someone snapped a picture.

Watching Schultz work a crowd, you can see why he would have made a natural candidate. But the political bug has faded. A lifelong Democrat, Schultz says he no longer thinks the government holds the answers to issues that concern him most. He has little interest in visiting Washington, and hasn’t made a presidential political contribution since supporting Barack Obama in 2008. Board member Mellody Hobson is even clearer: “Howard knows himself well enough to realise that a role in national politics isn’t right for him.”

Yet Schultz can’t surrender his dream of fixing America. At the very least, he can make Starbucks itself a laboratory for developing a better society. In the past year, Starbucks has set up 19 cafes on the edge of military bases, going out of its way to hire veterans and active-duty spouses to work there. Another initiative is a partnership with other big companies to convene giant job fairs in cities such as Phoenix, Chicago and Los Angeles, inviting out-of-work young adults for job interviews. A third programme, started in 2014, provides baristas and other employees a chance to earn an online college degree from Arizona State University—with Starbucks absorbing all tuition costs.

At most companies, any CEO so immersed in social causes would risk a shareholder mutiny. Schultz can’t ignore his investors; he owns just under 3 percent of the company. But Starbucks is a special case, says Chief Financial Officer Scott Maw, who joined the coffee company in 2011 after many years in the hard-nosed cultures of General Electric and JPMorgan Chase. When you’re selling lattes instead of locomotives or loans, Maw observes, a $3.45 grande isn’t just a beverage; it’s a ticket into “a pleasant experience and an ethically sound way of doing things”. Schultz’s crusades have become part of the product, morphing Starbucks into one of the biggest social businesses on the planet.

“Howard Schultz has always wanted to do something bigger than selling caffeine,” says Bryant Simon, a history professor at Temple University who wrote Everything but the Coffee, a 2009 book about Starbucks. Simon is the gadfly who won’t go away, contending that most of Schultz’s initiatives are brilliantly positioned mirages. Take Ethos, the Starbucks-owned house brand of bottled water. Customers may be excited that five cents of their purchase goes toward providing people access to clean water. In truth, when bottled water costs $1.8 a container, Starbucks keeps 97 percent of the purchase price.

Even the free-college initiative displeases Simon, who regards it as a public relations stunt, meant to convince Starbucks customers that baristas aren’t trapped in a dead-end job. “We’re supposed to believe that they’re all working toward a better future, with their employer covering the tab,” Simon remarks. “I wonder how many baristas will ever get a degree.”

Schultz wonders, too. The free-college initiative with ASU started about two years ago—and 5,000 employees have already enrolled. To date 44 have earned degrees. Another 100-plus expect to graduate this spring. It’s a struggle for baristas to get their old community-college credits transferred into the ASU system, to settle on a major and to meet all the deadlines for registration, term papers and the like. Since announcing the programme, both Starbucks and ASU have stepped up efforts to coach these online students through the full college process, rather than just handing them a student log-in code and hoping for the best. The graduation rate will likely keep climbing, but it could take another three or four years before the programme’s results are clear.

Most executives don’t have that much time. Periodically, Schultz gets calls from younger executives who want to know how they, too, can advocate for social causes without running the risk of getting fired. Marvin Ellison, the CEO of JC Penney, has sought him out. So has John Zimmer, the president of Lyft, the San Francisco ride-sharing company. Schultz’s blunt advice: “You have to earn the right.” Spend years winning investors’ trust by delivering strong results. Once you’ve done that, your degrees of freedom increase greatly. Get excited about non-business goals too early, and the trapdoor of termination can open at any time.

If the big boss needs to ratify everything, though, decision making slows to a crawl. Mindful of his own limits, Schultz has beefed up Starbucks’ management team in recent years with a wide range of proven leaders from outside. These include a chief operating officer with a Microsoft background (Kevin Johnson) and a chief strategist with a Disney pedigree (Matt Ryan). “There’s a lot more here than just The Howard Show,” says JC Penney Chairman Myron Ullman, who has been a Starbucks director since 2003. “Leadership doesn’t have to come from Howard on every topic.”

The payoff: Growth that never stops. Starbucks’ stock surged 48 percent in 2015, and despite a choppy start to 2016, the company’s market capitalisation is approaching $86 billion. While coffee remains the main event, food offerings keep expanding, with sales that have more than doubled in the past five years. (Why not pair that cappuccino with a chicken artichoke sandwich on ancient-grain flatbread?) Customer lines move faster, now that 16 million patrons are signed up for Starbucks’ mobile payment app. Fewer people fumble for change, sales per hour increase and profitability inches higher. Starbucks’ margins before interest and taxes run at 19.7 percent, double the likes of Chipotle or Panera.

More fun lies ahead, say Wall Street analysts, who expect Starbucks to keep expanding margins by one percentage point a year until at least 2018. Even controversies end up being good for business, as shown by a kerfuffle last November when Starbucks offered red cups that didn’t include any reference to the Christmas holidays. A few evangelists got upset. Television stations rushed to cover the ‘story’ and the amped-up attention helped Starbucks ring up record sales.

Sometimes winning ideas happen in spite of Schultz, rather than because of him. In 2008 Schultz angrily insisted that Starbucks stop selling melted-cheese breakfast sandwiches, because the smell of toasted cheddar was overwhelming the gentler aroma of fresh-brewed coffee. Guess what? Melted cheese made a comeback. The new version is cooked at 500 degrees Fahrenheit instead of 1,100 and with smaller slices of medium cheddar instead of big slices of sharp cheddar. “Howard can always be convinced,” says Luigi Bonini, Starbucks’ head of product development.

Rather than try to do everything, Schultz lately has been gravitating toward Starbucks’ newest, fastest-growing projects—which mesh well with his underdog mindset. He has become Mr. China, making quarterly trips to Beijing and Shanghai as well as a host of inland cities where Starbucks has big ambitions. Right now those stores mostly sell tea, Frappuccinos and mooncakes in the afternoon. Before long, Schultz says with a smile, China may embrace “the morning ritual” of coffee, too.

Starbucks now has 2,000 stores in China, quadruple its total just five years ago. Shanghai (432) has overtaken Seoul and New York as the city with the most Starbucks cafes. Other companies’ CEOs may stress about China’s recent stumbles; not Schultz. He believes an unstoppable expansion of China’s middle class will benefit his company, regardless. “One day,” Schultz told analysts in January, China “could very well be larger than the US business”.

Schultz’s other big project: Defending the high end of the coffee market with aplomb. He’s seen mass-market brands like Budweiser and Hershey lose allure as microbreweries and artisanal chocolate makers position themselves as the true champions of taste. Nobody will trap Starbucks that way, he vows. Yes, the coffee scene now includes ambitious upstarts like Philz, Blue Bottle, Intelligentsia and Stumptown that are turning heads with ultrafancy beans and serving styles. And, yes, the newcomers have raised the stakes by marketing, say, 12-ounce bags of Three Africans (a blend of Ethiopian and Congolese beans) for $15.75.

Schultz isn’t fazed. He’s jousting back with smaller packages of even pricier beans, packaged in distinctive bags as Starbucks Reserve. An 8.8-ounce pouch of pure Ethiopia Yirgacheffe Chelba goes for $17.50, perched among other upscale offerings in their own showcase in regular Starbucks stores, along with artful marketing promotion (‘Exotic, rare, exquisite’). The fanciest coffees show beautifully in Seattle’s ultra-elegant Roastery and Schultz plans to make the most of that pairing, with plans to open more Roasterys in the US and Asia. Schultz keeps e-mailing board members his iPhone photos of the Roastery in action, day or night. “Howard’s a fanatic,” says Starbucks director Hobson.

Starbucks’ directors retire at age 75, which is 13 years away for Schultz. He says he may step down as CEO before then. He kicked himself upstairs to the role of just chairman once before, from 2000 to 2007, so he could try other diversions such as owning the Seattle SuperSonics basketball team. Starbucks’ performance faltered, and Schultz reinstated himself as CEO in a boardroom coup. He says he’s pacing himself better this time around, listening more and showing more patience with other people. Running a big company “is a young man’s game, in terms of the energy required, the stamina, the curiosity,” Schultz concedes. Even so, he says he plans to stick around a while longer. His mission is not fully accomplished.

Cedric King lost both his legs in 2012 when he stepped on an improvised bomb during combat in Afghanistan. About 19 months later, his path crossed with Howard Schultz’s at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. The wounded Army Ranger was stuck in a wheelchair, struggling to master a pair of prosthetic limbs in hopes of walking again. Schultz was collecting stories of courage and struggle for a book that he and a co-writer were developing about America’s veterans. Everyone chatted for about an hour in the hospital’s cafeteria. “It was a nice conversation,” King recalls, “but I didn’t think I’d ever see Howard Schultz again.”

Not so. After Schultz and King swapped e-mails, in the summer of 2015 someone from Schultz’s family foundation called King with an unusual proposition. The foundation was helping to organise a series of job fairs around the US, aimed at America’s most unemployable young adults. The event could use some motivational speakers. King had been busy competing in marathons and triathlons. Would he be willing to come to Chicago, as a paid speaker? How about Phoenix? How about Los Angeles?

Take a close look at how Schultz spends his time, and it’s startling how often he hurls himself into the emotional tornadoes of other people’s troubles, hoping he can be a force for good. When former SuperSonics star Vin Baker ended up broke and struggling with the ravages of alcoholism, Schultz helped set him up in a Starbucks management programme so he could learn to run stores. When death-row attorney Bryan Stevenson wrote Just Mercy, a book about his struggles to free wrongly convicted inmates, Schultz insisted that Starbucks cafes sell the work—even if it seemed like a crazy juxtaposition— next to the cash register’s usual fare of biscotti and almonds.

Reading Just Mercy wasn’t enough. Schultz invited his way into Stevenson’s offices and spent part of a morning with Anthony Ray Hinton, a man freed after nearly three decades in Alabama’s prison system. “Mr. Hinton hadn’t held a fork in 30 years,” Schultz told me. “He had zero bitterness. He was just a calm, timid, elderly man. Meeting him was a life-changing experience.” The Alabama lawyer’s book graced Starbucks stores for months, becoming a New York Times bestseller. After such intense experiences, staying in the corner office and engaging in cheque book philanthropy “isn’t fulfilling for me,” says Schultz.

Remember Hurricane Katrina? Three years later, when Starbucks employees volunteered en masse to help New Orleans rebound, Schultz found himself at a home-rebuilding project. Spying a ladder and a bucket of paint on-site, Schultz announced that he wanted to help paint the house, too. “Howard had a bad back at the time,” Starbucks executive Rodney Hines recalled. “We tried to stop him. But he wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

Remember Ferguson? Schultz last year paid a call to that troubled Missouri town, too. Instead of taking the short route to and from the St. Louis airport, he meandered through back streets, gawking at plywood-boarded windows and ruined homes marked for demolition. Partway through the drive, two companions recall, Schultz declared: “We need to have a store in this city”. Since then ground has been broken; a store is being built and is in the process of hiring 20 to 25 people. Opening day is set for this spring.

Spurring Schultz on are moody memories of the crises he didn’t fix early in his career. In the mid-1980s, he recalls, he made his first business trip to Guatemala, checking up on bean suppliers. Growers whispered that only a small fraction of the money Schultz’s company was paying was ending up in growers’ pockets. Guatemala’s payment system was rife with kickbacks and undisclosed “commissions”. Schultz felt he was too new and puny to do anything about it; that inaction rankles him to this day.

An increasing number of Schultz’s projects are being conducted through the $100-million Schultz Family Foundation, which he and his wife, Sheri, oversee. The foundation currently holds only a thin slice of his wealth, but he says it will become much bigger in the years ahead. Its current priorities: Helping veterans resettle into the US economy and promoting job initiatives for people aged 16 to 24 who aren’t in school and haven’t found work.

At a recent foundation-sponsored jobs fair in Los Angeles, Starbucks was one of over 30 employers seeking recruits. Even so, Schultz was everywhere: Chatting with Latino and African-American attendees about their aspirations, apologising for his navy-blue suit (“It’s my armour”)—and squeezing onto the convention centre’s main concrete floor to become part of the mosh-pit throng absorbing Army Master Sergeant King’s talk.

Sweat dripping from his brow, the wounded soldier bellowed out his message to 6,000 attendees. “The only thing that matters is your attitude!” he declared. “I don’t have legs now, but this is what I’ve got to work with.” Abruptly, King lifted a cuff of his pinstripe trousers, revealing a rod where his shin used to be. People gasped. A moment later King delivered his payoff line: “You’ve got to find a way to take whatever you’ve got—and make it work for you.”

Fifteen feet from the stage the president of coffee nation was beaming. It was as if he were hearing King’s story for the first time. Hope was sweeping through the hall. Schultz wanted to inhale this pheromone as deeply as possible.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)