Jared Kushner: The brain behind Donald Trump's electoral campaign

The secret weapon of the Trump campaign: His son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who created a stealth data machine that leveraged social media and ran like a Silicon Valley startup. The inside story of the biggest upset in modern political history

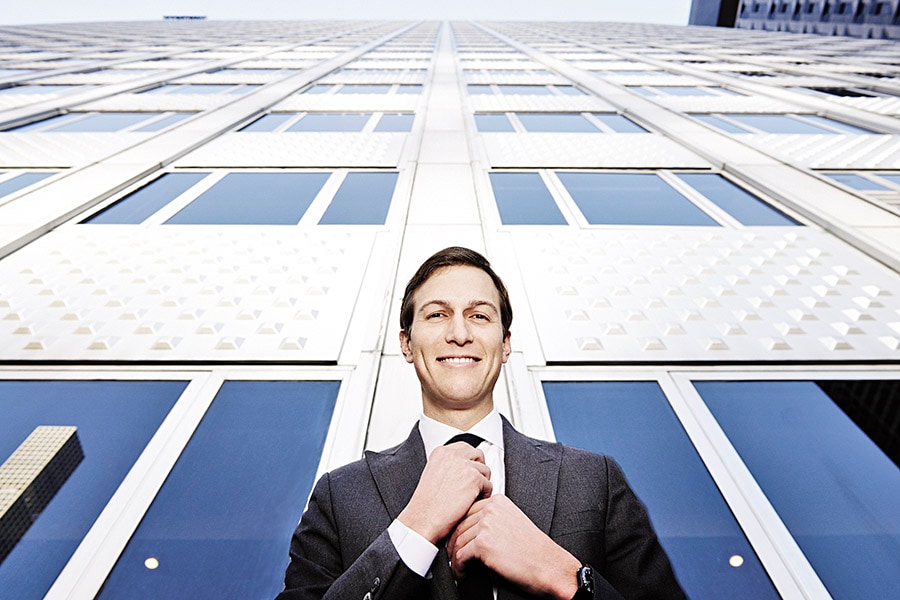

Image: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

It’s been one week since Donald Trump pulled off the biggest upset in modern political history, and his headquarters at Trump Tower in New York City is a 58-storey, onyx-glassed lightning rod. Barricades, TV trucks and protesters frame a fortified Fifth Avenue. Armies of journalists and selfie-seeking tourists stalk Trump Tower’s pink marble lobby, hoping to snap the next political power player who steps into view. Twenty-six floors up, in the same building where washed-up celebrities once battled for Trump’s blessing on The Apprentice, the president-elect is choosing his cabinet, and this contest contains all the twists and turns of his old reality show.

Winners will emerge shortly. But today’s focus is on the biggest loser: New Jersey governor Chris Christie, who has just been fired from his role leading the transition, along with most of the people associated with him. The episode is being characterised as a “knife fight” that ends in a “Stalinesque purge”.

The most compelling figure in this intrigue, however, wasn’t in Trump Tower. Jared Kushner was three blocks south, high up in his own skyscraper, at 666 Fifth Avenue, where he oversees his family’s Kushner Companies real estate empire. Trump’s son-in-law, dressed in an impeccably tailored grey suit, displays the impeccably polite manners that won the 35-year-old a dizzying number of influential friends even before he had gained the ear, and trust, of the new leader of the free world.

“Six months ago, Governor Christie and I decided this election was much bigger than any differences we may have had in the past, and we worked very well together,” he says. “The media has speculated on a lot of different things, and since I don’t talk to the press, they go as they go, but I was not behind pushing out him or his people.”

The speculation was well-founded, given the story’s Shakespearean twist: As a US attorney in 2005, Christie jailed Kushner’s father on tax evasion, election fraud and witness tampering charges. Revenge theories aside, the buzz around Kushner was directional and indicative. A year ago, he had zero experience in politics and about as much interest in it. Suddenly he sits at its global centre. Whether he plunged the dagger into Christie—Trump insiders insist the Bridgegate scandal did him in—is less important than the fact that he easily could have. And that power comes well-earned.

Kushner almost never speaks publicly—his chats with Forbes mark the first time he has talked about the Trump campaign or his role in it—but interviews with him and a dozen people around him and the Trump camp lead to an inescapable fact: The quiet, enigmatic young mogul delivered the presidency to the most fame-hungry, bombastic candidate in American history.

“It’s hard to overstate and hard to summarise Jared’s role in the campaign,” says billionaire Peter Thiel, the only significant Silicon Valley figure to publicly back Trump. “If Trump was the CEO, Jared was effectively the chief operating officer.”

“Jared Kushner is the biggest surprise of the 2016 election,” adds Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google, who helped design the Clinton campaign’s technology system. “Best I can tell, he actually ran the campaign and did it with essentially no resources.”

Image: Mark Wilson / Getty Images

No resources at the beginning, perhaps. Underfunded throughout, for sure. But by running the Trump campaign—notably, its secret data operation—like a Silicon Valley startup, Kushner eventually tipped the states that swung the election. And he did so in a manner that will change the way future elections will be won and lost. President Obama had unprecedented success in targeting, organising and motivating voters. But a lot has changed in eight years. Specifically social media. Clinton did borrow from Obama’s playbook but also leaned on traditional media. The Trump campaign, meanwhile, delved into message tailoring, sentiment manipulation and machine learning. The traditional campaign is dead, another victim of the unfiltered democracy of the web—and Kushner, more than anyone not named Donald Trump, killed it.

That achievement, coupled with the personal trust Trump has in him, uniquely positions Kushner to be a power broker of the highest order for at least four years. “Every president I’ve ever known has one or two people he intuitively and structurally trusts,” says former secretary of state Henry Kissinger, who has known Trump socially for decades and is currently advising the president-elect on foreign policy issues. “I think Jared might be that person.”

Jared Kushner’s ascent from Ivanka Trump’s little-known husband to Donald Trump’s campaign saviour happened gradually. In the early days of the scrappy campaign, it was all hands on deck, with Kushner helping research policy positions on tax and trade. But as the campaign gained steam, other players began using him as a trusted conduit to an erratic candidate. “I helped facilitate a lot of relationships that wouldn’t have happened otherwise,” Kushner says, adding that people felt safe speaking with him, without risk of leaks. “People were being told in Washington that if they did any work for the Trump campaign, they would never be able to work in Republican politics again. I hired a great tax-policy expert who joined under two conditions: We couldn’t tell anybody he worked for the campaign, and he was going to charge us double.”

Kushner’s role expanded as the Trump ticket gained traction—so did his enthusiasm. Kushner went all-in with Trump last November after seeing his father-in-law pack a raucous arena in Springfield, Illinois, on a Monday night. “People really saw hope in his message,” he says. “They wanted the things that wouldn’t have been obvious to a lot of people I would meet in the New York media world, the Upper East Side or at Robin Hood [Foundation] dinners.” And so this Harvard-educated child of privilege put on a bright-red Make America Great Again hat and rolled up his sleeves.

A power vacuum awaited him at Trump Tower. When Forbes visited the Trump campaign floor in the skyscraper a few weeks before Kushner’s Springfield epiphany, there was literally nothing there. No people—and no desks or chairs or computers awaiting the arrival of staffers. Just campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, spokesperson Hope Hicks and a strategy that centred on Trump making headline-grabbing statements, often by calling in to television shows, supplemented by a rally once or twice a week to provide the appearance of a traditional campaign. It was the epitome of the super-light startup: To see how little they could spend and still get the results they wanted.

Kushner stepped up to turn it into an actual campaign operation. Soon he was assembling a speech and policy team, handling Trump’s schedule and managing the finances. “Donald kept saying, ‘I don’t want people getting rich off the campaign, and I want to make sure we are watching every dollar just like we would do in business’.”

That structure provided a baseline, though still a blip compared with Hillary Clinton’s state-by-state machine. The decision that won Trump the presidency started on the return trip from that Springfield rally last November aboard his private 757, dubbed Trump Force One. Chatting over McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish sandwiches, Trump and Kushner talked about how the campaign was underutilising social media. The candidate, in turn, asked his son-in-law to take over his Facebook initiatives.

Image: Taylor Hill / Getty Images

Despite his itchy Twitter finger, Trump is a Luddite. He reportedly gets his news from print and television, and his version of email is to handwrite a note that his assistant will scan and attach. Among those in his close circle, Kushner was the natural pick to create a modern campaign. Yes, like Trump he’s primarily a real estate guy, but he had invested more broadly, including in media (in 2006 he bought the New York Observer) and digital commerce (he helped launch Cadre, an online marketplace for big real estate deals). More important, he knew the right crowd: Co-investors in Cadre include Thiel and Alibaba’s Jack Ma—and Kushner’s younger brother, Josh, a formidable venture capitalist who also co-founded the $2.7 billion insurance unicorn Oscar Health.

“I called some of my friends from Silicon Valley, some of the best digital marketers in the world, and asked how you scale this stuff,” Kushner says. “They gave me their subcontractors.”

At first, Kushner dabbled, engaging in what amounted to a beta test using Trump merchandise. “I called somebody who works for one of the technology companies that I work with, and I had them give me a tutorial on how to use Facebook micro-targeting,” Kushner says. Synched with Trump’s blunt, simple messaging, it worked. The Trump campaign went from selling $8,000 worth of hats and other items a day to $80,000, generating revenue, expanding the number of human billboards—and proving a concept. In another test, Kushner spent $160,000 to promote a series of low-tech policy videos of Trump talking straight into the camera that collectively generated more than 74 million views.

By June, the GOP nomination secured, Kushner took over all data-driven efforts. Within three weeks, in a nondescript building outside San Antonio, he had built what would become a 100-person data hub designed to unify fundraising, messaging and targeting. Run by Brad Parscale, who had previously built small websites for The Trump Organization, this secret back office would drive every strategic decision during the final months of the campaign.

Kushner structured the operation with a focus on maximising the return for every dollar spent. “We played Moneyball, asking ourselves which states will get the best ROI for the electoral vote,” Kushner says. “I asked, How can we get Trump’s message to that consumer for the least amount of cost?” FEC filings through mid-October indicate the Trump campaign spent roughly half as much as the Clinton campaign did.

Just as Trump’s unorthodox style allowed him to win the Republican nomination while spending far less than his more traditional opponents, Kushner’s lack of political experience became an advantage. Unschooled in traditional campaigning, he was able to look at the business of politics the way so many Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have sized up other bloated industries.

Television and online advertising? Small and smaller. Twitter and Facebook would fuel the campaign, as key tools for not only spreading Trump’s message but also targeting potential supporters, scraping massive amounts of constituent data and sensing shifts in sentiment in real time.

“We weren’t afraid to make changes. We weren’t afraid to fail. We tried to do things very cheaply, very quickly. And if it wasn’t working, we would kill it quickly,” Kushner says. “It meant making quick decisions, fixing things that were broken and scaling things that worked.”

This wasn’t a completely raw startup. Kushner’s crew was able to tap into the Republican National Committee’s data machine, and it hired targeting partners like Cambridge Analytica to map voter universes and identify which parts of the Trump platform mattered most: Trade, immigration or change. Tools like Deep Root drove the scaled-back TV ad spending by identifying shows popular with specific voter blocks in specific regions—say, NCIS for anti-ObamaCare voters or The Walking Dead for people worried about immigration. Kushner built a custom geo-location tool that plotted the location density of about 20 voter types over a live Google Maps interface.

Soon the data operation dictated every campaign decision: Travel, fundraising, advertising, rally locations. “He put all the pieces together,” Parscale says. “And what’s funny is the outside world was so obsessed about this little piece or that, they didn’t pick up that it was all being orchestrated so well.”

For fundraising, they turned to machine learning, installing digital marketing companies on a trading floor to make them compete for business. Ineffective ads were killed in minutes, while successful ones scaled. The campaign was sending more than 100,000 uniquely tweaked ads to targeted voters each day. In the end, the richest person ever elected president, whose fundraising effort was ridiculed at the beginning of the year, raised more than $250 million in four months—mostly from small donors.

As the election barrelled toward its finale, Kushner’s system provided both ample cash and the insight on where to spend it. When the campaign registered the fact that momentum in Michigan and Pennsylvania was turning Trump’s way, Kushner unleashed tailored TV ads, last-minute rallies and thousands of volunteers to knock on doors and make phone calls.

And until the final days of the campaign, he did all this without anyone on the outside knowing about it. For those who can’t understand how Hillary Clinton could win the popular vote by at least 2 million yet lose handily in the electoral college, perhaps this provides some clarity. If the campaign’s overarching sentiment was fear and anger, the deciding factor at the end was data and entrepreneurship.

“Jared understood the online world in a way the traditional media folks didn’t. He managed to assemble a presidential campaign on a shoestring using new technology and won. That’s a big deal,” says Schmidt. “Remember all those articles about how they had no money, no people, organisational structure? Well, they won, and Jared ran it.”

Controlled, understated and calm, Jared Kushner couldn’t be more different from his father-in-law. Take Twitter. While Trump’s impulsive tweeting to his 15.5 million followers forced his staff to withhold his phone during parts of the campaign, Kushner—who has had a verified account since April 2009—has never posted a single tweet.

And whereas Trump’s office is wall-to-wall Donald, a memorabilia-stuffed shrine to ego, the headquarters for the Kushner Companies is sparse and sober. A leather-bound copy of Jewish teachings, the Pirkei Avot, sits on a wooden pedestal in the reception room, and identical silver mezuzahs adorn the side of each office door. The only decoration in his large, terraced boardroom is an oil painting of his grandparents. But enter Kushner’s corner office and you see—under a painting with the words ‘Don’t Panic’ over a canvas of New York Observer pages—two critical commonalities that unite the pair: Columns of real estate deal trophies and framed photos of Ivanka. If you are looking for a consistent ideology from either Kushner or Trump, it can be summarised in a word: Family.

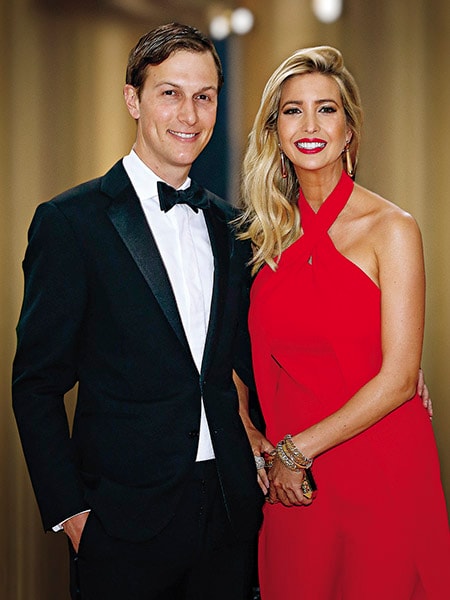

Jared and Ivanka met at a business lunch and started dating in 2007. During the courtship, Kushner had met Donald only a few times in passing when, sensing the relationship was getting serious, he asked Trump for a meeting. Over lunch at the Trump Grill (which Trump briefly made a household name with his infamous taco bowl tweet), they discussed the couple’s future. “I said, ‘Ivanka and I are getting serious, and we’re starting to go down that path’,” Kushner says and laughs.

“He said, ‘You’d better be serious on this’.”

“Jared and my father initially bonded over a combination of me and real estate,” Ivanka Trump says. “There’s a lot of parallels between Jared as a developer and my father in the early years of his development career.”

Like Trump, Kushner grew up outside Manhattan: New Jersey in Kushner’s case, versus Trump’s Queens. Also like Trump, Kushner is the son of a man who created a real estate empire in his local market—Charles Kushner eventually controlled 25,000 apartments across the Northeast—and steeped his children in the family business. “My father never really believed in summer camp, so we’d come with him to the office,” Kushner says. “We’d go look at jobs, work on construction sites. It taught us real work.” Raised with three siblings in an observant Jewish home in Livingston, New Jersey, Kushner went to a private Jewish high school and then to Harvard. Next came New York University, for a joint JD and MBA.

His father was a huge supporter of Democrats, giving $1 million to the Democratic National Committee in 2002 and $90,000 to Hillary Clinton’s Senate run in 2000, and Jared largely followed suit, with more than $60,000 to Democratic committees and $11,000 to Clinton. During grad school, Kushner interned for Manhattan’s longtime district attorney, Robert Morgenthau, before a family scandal upended his life. In 2004, Charles Kushner pleaded guilty to tax evasion, illegal campaign contributions and witness tampering. The latter charge brought national tabloid attention. Angry that his brother-in-law was talking to prosecutors, Charles had paid a prostitute to entrap him—a tryst that he secretly taped and then mailed to his sister.

Just 24, Jared, as the elder son, suddenly found himself charged with keeping the family together. He saw his mother most days and flew to Alabama to visit his father in prison on most weekends. He also developed a deeper bond with his brother, Josh, who had just started Harvard when the scandal broke. Says Josh, who considers Jared his best friend: “He is the person that I turn to for guidance and support no matter the circumstance.”

“The whole thing taught me not to worry about the things you can’t control,” Kushner says. “You can control how you react and can try to make things happen as you want them to. I focus on doing my best to ensure the outcomes. And when it doesn’t go my way, I have to work harder the next time.”

That applied to the family business, too, which Kushner now led. To start fresh, he took aim at Manhattan, just as Trump did 40 years before, determined to play in America’s most lucrative and competitive real estate market.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. His first big purchase as CEO of the Kushner Companies, 666 Fifth, for a record-breaking $1.8 billion, closed in 2007—just in time for the financial crisis. Rents fell, leases broke, funding vanished. To stay solvent, Kushner sold 49 percent of the building’s retail space to the Carlyle Group and others for $525 million and seemingly restructured every loan agreement possible, showing a willingness to pay more down the road for room to breathe in the short term. In the end, he avoided the kind of bankruptcy manoeuvres that Trump pulled in the 1990s and weathered the storm.

Kushner had learnt a lesson. Rather than chase top-dollar, blue-chip addresses around New York, he would try to ride up with cooler, up-and-coming neighbourhoods, which he has done to the tune of $14 billion worth of acquisitions and developments, in places like Manhattan’s SoHo and East Village and Brooklyn’s Dumbo. “Jared brings a youthful perspective, an innovative mindset, to a very traditional industry that’s comprised of predominantly 70-year-old men,” Ivanka Trump says. He has also pushed into resurgent areas—Astoria, Queens, and Journal Square in Jersey City—that were once the stomping grounds of Fred Trump and Charles Kushner, respectively.

Part of the reason Jared Kushner has engendered such public interest, besides the power he suddenly wields and the curiosity generated by his near-invisible media presence, is the paradoxes that he represents.

He brought the Silicon Valley ethos, which values openness and inclusiveness, to a campaign that promised closed borders, trade protection and religious exclusion. He is the scion of prodigious Democratic donors yet steered a Republican presidential campaign. A grandson of Holocaust survivors who serves a man who has advocated a ban on war refugees. A fact-driven lawyer whose chosen candidate called global warming a hoax, linked vaccines to autism and challenged President Obama’s citizenship. A media mogul in a campaign stoked by fake news. A devout Jew advising a president-elect embraced by the alt-right and supported by the KKK.

Kushner’s answers to these conflicts come down to one core conviction—his unflagging faith in Donald Trump. A faith that, ironically, given his role in the campaign, he defends with the “data” he’s accumulated about the man over a decade-plus relationship.

“If I know somebody and everyone else says that this person’s a terrible person,” he says, “I’m not going to start thinking that this person’s a terrible person or disassociating myself, when my empirical data and experience is a lot more informed than many of the people casting these judgements. What would that say about me if I changed my view based on what other people think, as opposed to the facts that I actually know for myself?”

Regarding Trump’s worldview: “I don’t think it’s very controversial in an election to become the president of the United States to say that your position is to put America first and to be nationalist as opposed to a globalist.”

As for Trump’s endless stream of statements that insulted and threatened Muslims, Mexicans, women, prisoners of war and US generals, among others? “I just know a lot of the things that people try to attack him with are just not true or overblown or exaggerations. I know his character. I know who he is, and I obviously would not have supported him if I thought otherwise. If the country gives him a chance, they’ll find he won’t tolerate hateful rhetoric or behaviour.”

On his political affiliation, he defines himself thus: “To be determined. I haven’t made a decision. Things are still evolving as they go.” He adds: “There’s some aspects of the Democrat Party that didn’t speak to me, and there are some aspects of the Republican Party that didn’t speak to me. People in the political world try to put you into different buckets based on what exists. I think Trump’s creating his own bucket—a blend of what works and eliminating what doesn’t work.” (Though in using the GOP-favoured pejorative “Democrat Party” over the traditional “Democratic Party,” Kushner gives a hint about the contents of his bucket.)

The allegations of anti-Semitism hit closer to home. In July, Trump tweeted a graphic of Hillary Clinton against a background of dollar bills and a six-pointed star that contained the words “most corrupt candidate ever”, an image that had allegedly originated on a white supremacist message board. Dana Schwartz, a reporter for Kushner’s Observer, wrote a widely read piece for the paper’s site urging her boss, given the prominence he places on his faith and family, to denounce the tweet. Kushner responded with an opinion piece that defended Trump using the same old line: That he knows Trump. “If even the slightest infraction against what the speech police have deemed correct speech is instantly shouted down with taunts of ‘racist’, then what is left to condemn the actual racists?”

Kushner insists today that there will be no hate element in the Trump Administration, starting at the top. “You can’t not be a racist for 69 years, then all of a sudden become a racist, right?” he says. “You can’t not be an anti-Semite for 69 years and all of a sudden become an anti-Semite because you’re running.”

His reaction to fringe elements, like the KKK and the white nationalist alt-right, who have embraced Trump? “Trump has disavowed their support 25 times. He’s renounced hatred, he’s renounced bigotry, and he’s renounced racism. I don’t know if he could ever denounce them enough for some people.” He then paraphrases a quote he attributes to Ronald Reagan: “Just because they support me doesn’t mean that I support them.”

Kushner’s support extends to Steve Bannon, Trump’s strategic advisor, who had been accused by his ex-wife of making anti-Semitic comments (he denies it) and whose website, Breitbart, has often published articles that dog-whistle racist, anti-Semitic sentiments. “Do you hold me accountable for every single thing that the Observer’s ever written, like they came from me?” Kushner says. “All I know about Steve is my experience working with him. He’s an incredible Zionist and loves Israel. He was one of the leaders in the anti-divestiture campaign. And what I’ve seen from working together with him was somebody who did not fit the description that people are pushing on him. I choose to judge him based on my experience and seeing the job he’s done, as opposed to what other people are saying about him.”

And that seems to reflect how Kushner feels about friends upset by his role in electing someone who offends their values, to the point where, before the election, several wrote to him in fits of pique. “I call it an exfoliation. Anyone who was willing to change a friendship or not do business because of who somebody supports in politics is not somebody who has a lot of character.

“People are very fickle,” he adds. “You have to find what you believe in, challenge your truths. And if you believe in something, even if it’s unpopular, you have to push with it.”

Many of those fickle friends are likely to return now that Kushner, after masterminding Trump’s stunning victory, has the ear of the future president. What he will do with that power is anyone’s guess.

For now, Kushner plays coy: “There’s a lot of people who have been asking me to get involved in a more official capacity. I just have to think about what that means for my family, for my business and make sure it’d be the right thing for a multitude of reasons.”

It’s unlikely that he can hold a formal position in the Trump White House. Nepotism laws established after President Kennedy made brother Bobby attorney general bar the president from giving government roles to relatives—including in-laws. Reports have stated that the administration is exploring every legal angle to get Kushner into the West Wing—including adding him as an unpaid advisor, though even that may be covered by the law, which was written to ensure fealty to the Constitution rather than the individual.

But it may be a moot point. With or without a government title or a $170,000 federal salary, there’s no law that bans a president from seeking counsel from whomever he wants. It’s clear America’s tech and entrepreneurial leaders, who heavily backed Clinton and collectively denounced Trump, will use Kushner as a go-between and that Trump will lean on him just as heavily.

“I assume he’ll be in the White House throughout the entire presidency,” says News Corp billionaire Rupert Murdoch. “For the next four or eight years, he’ll be a strong voice, maybe even the strongest after the vice president.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)