Loxo: One patient at a time

Companies large and small are competing to attack rare genetic mutations that cause cancer. The reason? Great science and high drug prices. The result? Soaring stock prices

“We look to generate crazy, over-the-top, exciting data that is great for patients,” says Loxo CEO Josh Bilenker, pictured alongside chief business officer Jacob Van Naarden (left)

“We look to generate crazy, over-the-top, exciting data that is great for patients,” says Loxo CEO Josh Bilenker, pictured alongside chief business officer Jacob Van Naarden (left)Image: David Yellen for Forbes

Allan Brandt, a 63-year-old history of medicine professor at Harvard, seems taken aback to have become part of medical history himself. In 2012, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia, a deadly cancer that had a potential cure: A bone marrow transplant. His sister was a match, and he went through the two-month-long ordeal twice, only to have the cancer return. “No one is going to do well with a third transplant,” he says grimly.

He was saved by a hot biotech trend: Medicines that are targeted to a protein made by a particular gene, often discovered by sequencing the cancer’s DNA. Sometimes they work in only a small number of people, requiring diagnostic testing. In Brandt’s case, Agios Pharmaceuticals, just a 15-minute ride from his Harvard office, had a drug that targeted a genetic mutation he was lucky enough to have. Only a few thousand of the 21,000 people diagnosed with AML each year do.

“This drug wasn’t available at all when I got sick,” Brandt says. “In the period of my illness, I’ve been able to get access to what I consider to be a lifesaving medication, and I’ve returned to health. As somebody who starts with a basic scepticism about medical technology and therapeutics, I have to say there are real possibilities for patients in these new developments.”

What drives drug companies to invest in markets of just a few thousand people? Speed is one reason—big benefits for very sick people mean smaller, shorter studies. One Agios drug, Idhifa, was approved by the Food & Drug Administration just four years after clinical trials started—a process that typically takes 12 years. Another reason to invest is price. Agios licenced Idhifa to Celgene, which charges $25,000 a month for it. (Brandt gets his medicine for free, because he’s in a clinical trial.)

The other reason is that the science is exploding, and the combination of better odds of success and faster timelines is drawing drug developers like moths to a flame. Josh Bilenker, an FDA-reviewer-turned-venture-capitalist at Aisling Capital, decided to focus on such drugs exclusively when he founded a company, Loxo Oncology, in 2013, selecting gene “targets” where there was good evidence they would prove effective, even if only in patients with a rare mutation. “Hit the target really hard, define your patients and just work like heck on the clinical-regulatory side,” Bilenker says.

The strategy paid off in June, when Loxo’s first drug presented stunning results: Of 50 patients who took it, 38 had their tumours shrink. (Updated results show tumours shrinking in 44 out of 55 patients.) The drug, larotrectinib, was tested against a rare mutation called TRK, which can produce tumours in the lungs, skin and brain. And Loxo took another unprecedented step. It had already started developing a second drug for patients whose tumours had become resistant to the first, so when patients are failed by the company’s first medicine, another option will be at the ready. It’s been tested in two patients.

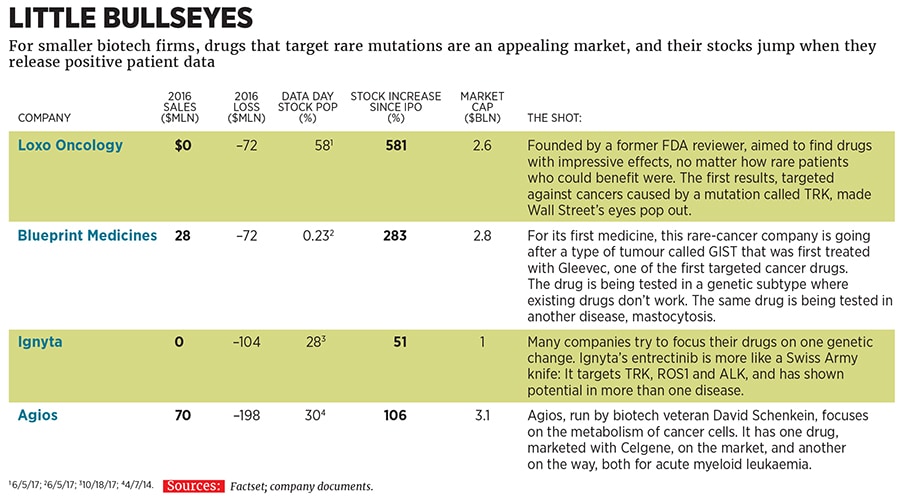

Loxo shares are up 175 percent so far this year, thanks to the excitement about larotrectinib and two other rare-cancer medicines it is developing. Other companies taking the rare-disease approach are doing equally well. Ignyta, which is testing a drug called entrectinib that targets TRK and a rare mutation called ROS1 that is a cause of lung cancers, is up 190 percent. Blueprint Medicines, focussed on drugs targeting other rare mutations, including a type of digestive-tract cancer, is up 150 percent. But Agios’s story should make investors cautious. That company’s shares are up 100 percent since its 2013 initial public offering, but down 50 percent from their high in January 2015. The results can be so great, investors forget how small the target markets are.

“There is not going be a silver bullet. There’s going to be a series of drugs that will lead to some pretty dramatic change,” says Agios chief executive David Schenkein

“There is not going be a silver bullet. There’s going to be a series of drugs that will lead to some pretty dramatic change,” says Agios chief executive David SchenkeinImage: Matt Furman for Forbes

Another problem: How will doctors find all these patients whose cancers have rare genetic mutations? That will involve using a diagnostic test—often a fancy, high-tech DNA sequencer—on the tumours of every patient who has been failed by standard medicines. Right now this happens mostly at major academic centres. Foundation Medicine in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is seeking FDA approval for a standardised test. Thermo Fisher Scientific—the laboratory tools company—and Illumina are also developing new diagnostic tools. “For the first time I think we can see the tide shifting on both the quality of testing and [patients’] access to it,” says Jacob Van Naarden, Loxo’s chief business officer. “It feels like it’s tangibly in sight but not here yet.”

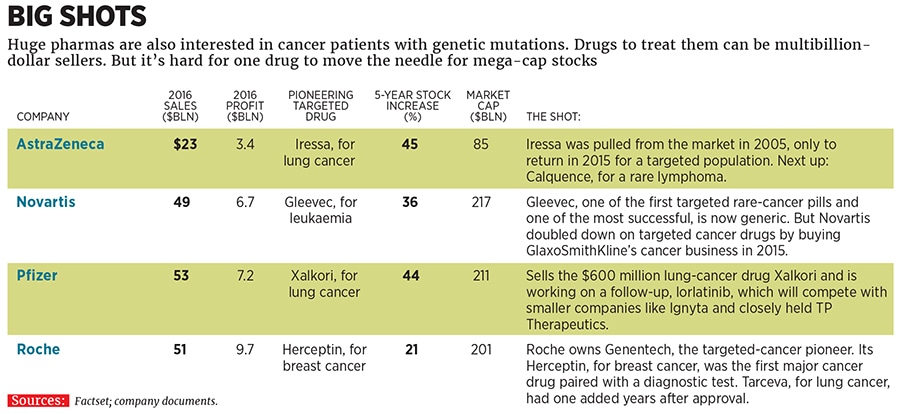

Small companies aren’t the only ones playing. The first big targeted drugs came from giants like Novartis, Pfizer and AstraZeneca, all of which are in the mix. “There is this Talmudic concept that the way to save humanity is one life at a time,” says José Baselga, the physician-in-chief at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “Our obligation is to question every dogma in drug development.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X