Oil Firm Chevron and its Cash Overflow

Chevron is unloved by investors and by the residents of its home base. No matter: John Watson has built a cash-laden profit machine that’s poised for the greatest oil strike in the history of energy

John Watson is an odd fit for an oilman. For one thing, he’s a Californian in an industry dominated by Texans, Saudis and Russians. A Bay Area native, no less, who attended the University of California in the 1970s and now lives minutes away from Berkeley. Instead of cutting his teeth in the oilfields like Exxon Mobil CEO Rex Tillerson or wildcatting billionaire Harold Hamm, Watson studied agricultural economics and started his oil career as a financial analyst, not a roughneck.

He’s an odd fit for California, too. Watson is, to use Mitt Romney’s term, ‘severely conservative’. At 6-foot-4, charismatic and silver-tongued, he’s a throwback to the Golden State of Chevron’s predecessor, Standard Oil of California. That was a time when fortunes came not via gaming apps or silicon chips but from mines gnawed into the Sierras and wells drilled in the dusty wastes of Bakersfield à la There Will Be Blood.

So, perhaps it’s fitting that this misfit CEO runs an odd-duck energy company, one that takes a contrarian strategy on almost every major trend. As his American rivals scoop up the frackable plots powering the great domestic oil and gas boom, Watson has largely taken a pass. And while global giants like Exxon Mobil, Cnooc and Rosneft have built themselves up through acquisitions of big companies like XTO Energy, Nexen and TNK-BP, Watson says he’s not doing any deals, despite a balance sheet fat with $22 billion in cash.

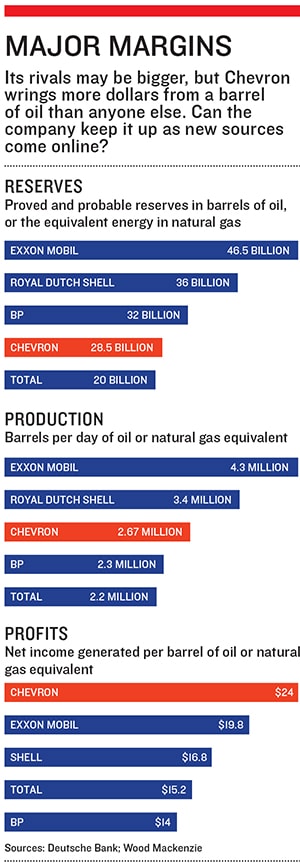

Watson’s quest has been focussed on cost-efficient reserves, particularly oil, which boasts better economics. Chevron generates a profit of $24 per barrel of oil versus Exxon’s $19.80, which is in line with Big Oil’s average. “We are always value-focussed on what we do. We are not barrel-focussed, per se,” says Watson.

So, while Watson needs to get bigger, he’s making an enormous bet that he can keep those efficiencies up by growing internally. How big is the wager? His capital expenditures have topped $100 billion over the past five years. Chevron will invest $37 billion this year alone—about the same as Exxon Mobil, despite having roughly half of its market cap ($225 billion versus $400 billion). “What differentiates us now is that we have a growth profile with more of the same,” says Watson. “We have more depth in our portfolio than we’ve ever had, and they are good projects.”

Taken together, Watson promises, these ‘good projects’ will boost the company’s oil and gas volumes by 25 percent to 3.3 million barrels per day in just four years, the rough equivalent of adding the capacity of Chesapeake Energy or Occidental Petroleum. That kind of euphoria is unheard of at oil companies these days. The balance of power has shifted towards the state-owned giants that sit on the world’s last deposits of highly lucrative easy oil. The publicly traded, vertically integrated giants like Exxon, Shell, BP and Total have had to go after deeper and trickier resources. All struggle just to keep output steady, while some have given up trying to stay big: Conoco-Phillips split itself up, and BP shed billions in assets after the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Exxon, despite its $40 billion acquisition of XTO Energy in 2010, has had five straight quarters of declining output.

The markets are just starting to notice. Chevron shares are 20 percent higher than they were two years ago, versus 0.5 percent among its Big Oil rivals and 18.5 percent for the S&P. Yet, with shares trading at just 8.6 times earnings, with a 3.1 percent dividend yield, investors seem leery of what amounts to numerous blank-cheque fishing expeditions. “The key question is less Chevron’s ability to grow, more the capex required to get there,” says Ed Westlake, analyst at Credit Suisse. Deutsche Bank analyst Paul Sankey adds that it’s hard to justify not returning that $22 billion in cash to shareholders given record-low interest rates and the fact that Chevron is carrying a relatively minuscule $12 billion in debt. Others wonder why Watson hasn’t gone shopping.

Ask Watson about that and he shrugs. “The idea that our balance sheet will drive us to an acquisition is not supported by our history or by anything that I or my predecessors have said.”

For Watson, internally growing a Chesapeake Energy-level of output over the next four years means a focussed number of massive bets. In Kazakhstan, Chevron will invest $25 billion more into the Tengiz megafield to take daily production to 1 million barrels from the current 750,000. In Nigeria, it’s investing $2 billion offshore as well as $8 billion to build the nation’s first gasto-liquids plant. In the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, Chevron has plowed in $12 billion to build out three more fields, which are projected to produce 100,000 barrels per day by 2015.

But as Forbes first reported in 2011, the real monster is Gorgon, a $52 billion liquefied natural gas joint venture in Australia that’s one of the biggest infrastructure projects of any kind on the planet. With more than 50 trillion cubic feet of gas discovered nearby, there’s enough gas not only to keep Gorgon going for 40 years but also to justify Chevron and its partners, including Shell and Apache, investing $29 billion in another LNG project nearby called Wheatstone.

Gorgon sits on Barrow Island, 37 miles off the northwest coast of Australia. Drilling in this isolated Eden, Chevron has been producing oil from Barrow since 1964. But since the new discovery, it has been working to turn Barrow into a massive hub for liquefied natural gas. As a condition for approval, Australia mandated quarantine rules that require all equipment, luggage and personnel to be inspected for even the most minute critters, seeds, bugs—anything that could disrupt the native ecology.

Aside from the potential for catastrophic environmental damage, Gorgon is risky for another reason. Investing $25 billion (Chevron’s half) in a megaproject planned and built over 10 years is very different from making a $25 billion acquisition of another company. With Gorgon, lots of things have changed since the first shovelful of dirt was turned in 2009.

Currency moves, for instance. Half of Gorgon’s costs are in Australian dollars, which have appreciated 20 percent against the greenback in recent years, adding $5 billion in costs. And with $200 billion in liquefied natural gas projects ongoing in Australia, labour inflation has added billions more. What’s more, when Gorgon was sanctioned, the US shale boom—and its crushing downward pressure on gas prices—didn’t yet exist. In fact, domestic gas supplies were getting tight enough that in 2006, Chevron entered into a 20-year contract with Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass terminal on the Gulf Coast, giving it the ability to import gas to the US, a laughable idea today.

Still, at least for now, the economics of Gorgon look secure. Deutsche Bank estimates that the initial project will generate an annual return on capital of 13 percent over the next 40 years, with a lot of upside potential as more exploration wells are drilled and additional processing plants added. All that cleaner, greener gas has already been pre-sold under 20-year contracts to buyers in Asia at prices indexed not to low-priced American gas but to high-priced oil. Aussie gas fetches upwards of $15 per thousand cubic feet, more than offsetting transportation and processing costs. Natural gas in America goes for $3.50.

Despite the price tags and risks, Watson sees these as value plays, betting that Chevron’s engineers can build oil and gas projects from scratch cheaper than it could buy similar assets on the market. Why overpay for what someone else has built when you can control your own destiny? And that’s where the balance sheet comes into play. “Cash is the risk mitigator that we have,” says Watson.

Watson’s build-versus-buy mindset was acquired the hard way. He joined Chevron in 1980, just in time to catch oil spiking to a record $35 a barrel ($100 in today’s dollars). After rising through the finance side, Watson was appointed president of Chevron Canada in 1996. Then came the dark days of 1998, when the ‘Asian flu’ helped gut oil prices to $11 a barrel. That same year, Watson was named to lead a newly created mergers and acquisitions group. It was he who in 2001 spearheaded Chevron’s $45 billion integration of Texaco. Four years later came the $18 billion purchase of Unocal.

What the acquisitions brought was a hodgepodge of overlapping holdings in places like Kazakhstan, Australia and Nigeria. Eventually, as CFO, Watson helped then CEO Dave O’Reilly develop systems to rank all these opportunities, discouraging investments that chased the flavour of the week, focusing instead on long-term projects that made economic sense. What Watson learnt, however, was that even on the most seemingly attractive projects, you need to bake in a big margin of error. He now thinks they have it down to a science. “What we have is a uniform process that gives us a consistent view of the geologic risk,” says Vice Chairman George Kirkland. From there, they overlay global economic and political factors. “That tells you where you first want to put your money,” says Kirkland.

That system often sends Chevron away from where the herd is going. In Russia in 2010, Chevron signed an exploration deal with Kremlin-controlled Rosneft to explore in the Black Sea region. A year later, Chevron backed out, deciding the geology wasn’t worth it. At the same time, BP, Exxon Mobil, Statoil, Total and Eni have forged deals with Rosneft, with Eni stepping into the Black Sea shoes that Chevron left. “We left on good graces,” shrugs Watson.

In Iraq, Chevron spent months studying every field being licensed by Baghdad. But while every other big oil company made one deal or another to rehab Iraq’s megafields, Chevron did not. Because the terms, a set fee of $1.50 per barrel produced, weren’t good enough. “We’re not a believer in loss leaders,” says Kirkland. “You can’t make money at $1.50 a barrel; it’s not competitive with other opportunities in the world.”

So last year, over objections from Baghdad, Chevron inked a production sharing contract with the Kurdish Regional Government in northern Iraq to drill new fields. It’s this insistence on value that kept Chevron from making a big deal in the North American shale boom. Exxon’s experience with XTO Energy has proved Watson right.

Last summer, CEO Rex Tillerson famously said, “We are all losing our shirts today” on shale gas. Likewise, ConocoPhillips paid $36 billion in 2006 to acquire gas-focussed Burlington Resources, only to write off $25 billion three years later.

In many shale plays what started off looking like a once-in-a-lifetime bonanza, back when natural gas prices were higher, has already turned bust as new supplies brought prices down to $3.50 per thousand cubic feet, below the costs of production.

But not for Chevron. The biggest deal Watson has done in the American shale boom was $4.3 billion for Marcellus Shale-based Atlas Petroleum. He went after Atlas because it already had a deal with India’s Reliance Industries to put up $1 billion toward the cost of drilling wells. As a result, says Watson, “we can drill very economically down to the prices that we have today”.

There’s another reason Watson didn’t invest billions in the US shale boom. He didn’t have to. Most oil giants pulled out of the onshore US in the 1990s, considering the assets too old and worn-out to be material to growth. Chevron stayed. The result: 3 million net acres in 13 unconventional oil and gas fields from coast to coast. “We never left,” says North American oil and gas chief Gary Luquette. “We knew these legacy assets represented potential. We just had to figure out how to develop the technical solutions and have them intersect with our business plan.” That technical solution was the combination of directional drilling and hydraulic fracking.

Chevron not only has a lot of shale acreage, but much of it has been in the company so long that Chevron owns it outright. As players like Chesapeake Energy have been churning through expensive capital to drill up newly acquired acreage before their leases run out, Chevron has the option to just bide its time.

A prime example is in California. As you can see for yourself at the La Brea Tar Pits in Hollywood, there’s still plenty of oil left in southern California; Chevron pumps out some 180,000 barrels every day from 100-year-old fields like Kern River in the San Joaquin Valley. Geologists think the Monterey Shale, which stretches from the coast near Santa Barbara clear over to the San Joaquin Valley, holds 15 billion barrels. Chevron already has a lot of land in the region. Why not drill there? Because it will cost more than Chevron’s other options. So, it waits.

Meanwhile, Chevron’s legacy positions in Texas can bear fruit right now. In contrast to the gas-rich shale formations, Chevron has found that much of its old West Texas acreage will produce oodles of highly profitable oil for decades to come. (Chevron’s Texas production is currently 110,000 barrels per day.) Last year, Watson added 400,000 acres there in a small acquisition from Chesapeake Energy.

Chevron has caught a similar break in the shallow coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico for a different reason. For years, the company liked having control and access to the maze of pipelines that crisscross the continental shelf because it made it cheaper to bring oil and gas to

market from the deepwater fields. Now the right-of-way play has yielded the potential for new oil and gas hoards, situated in shallow waters but deeper under the seafloor than anyone thought possible (farther down than Mount Everest reaches up).

Whereas the logistical hurdles surrounding ultradeep wells (mostly pressure-related) have scared off the likes of Exxon, Chevron has partnered with McMoRan Exploration to snap up dozens of leases in a government auction. While watching McMoRan spend more than $1 billion trying to complete its Davy Jones well, Chevron has begun drilling its own ultradeep well just onshore.

If it is successful, those nearby Chevron pipelines will make it far easier to flow the gas to market. It’s a classic heads-I-win, tails-you-lose, says Chevron’s Luquette: “We’re happy to let other people use their money to prove how to do these things.”

Watson is, ultimately, a pragmatist. He has forged such a close relationship with California Governor Jerry Brown that the two recently huddled for a two-hour one-on-one meeting to discuss the state’s myriad problems.

Yet he’s under no illusions: The citizens of America’s most populous state hate its largest company (in terms of sales). Activists routinely gather outside Watson’s house in the bucolic Bay Area enclave of Lafayette to protest Chevron’s environmental record, accusing it of covering up oil spills in Ecuador and carelessly causing a deadly blowout in Nigeria’s waters and a spill off the coast of Brazil. A recent refinery fire in Richmond, California, which spewed thick smoke across the region and jacked up gas prices statewide, didn’t help matters. And new statewide cap-and-trade rules will put a big bite on carbon emitters, though Chevron’s two refineries, the biggest and most efficient in the state, should survive.

“California has been a trendsetter in many areas, and most of them have been positive over time. Air emissions are down. The state’s air and water are much cleaner,” says Watson. And yet, “no energy-intensive business would choose to locate here. So, what you’ll get is a migration of businesses—a rapid deindustrialisation. California will effectively export carbon and the jobs that go with it”.

In December, Chevron announced it was moving 800 of 3,500 head-quarters jobs from San Ramon to Houston. And yet, he also recognises that as California goes, so goes the nation. If the rest of the industry can be accused of groupthink, why not make the best of it? “There are some pluses in being here,” he says. “It gives you a window on what a non-oil community thinks about our industry. That helps prepare us for what we see around the world.”

Expensive Problems

John Watson would never admit it, but there’s another reason it’s not a bad idea for Chevron to hold on to its $22 billion cash pile. Simply put: When you run one of the world’s biggest oil companies, stuff happens. Billions of dollars of stuff.

In Ecuador in 2011, a judge levied an $18 billion judgment against Chevron in a decades-long case over whether or not the company is responsible for oil spills in the rain forest.

“It’s a fraud,” says Watson.

So far, the evidence seems to back him up. In January, a former Ecuadoran judge who presided over the early stages of the case swore that he was paid thousands of dollars by the plaintiffs’ lawyers. He also insisted that the plaintiffs’ attorneys bribed the judge who issued the $18 billion ruling, promising him $500,000 out of any proceeds in exchange for allowing them to ghostwrite the final ruling in the case. Chevron previously got another judge disqualified after releasing videos showing discussions of bribes and kickbacks.

Image: Ricardo Moraes / Reuters

Investors just want to know when it will end. “The short answer is, it will end when the plaintiffs’ lawyers give up,” says Watson.

Then there’s Brazil, where Chevron drilled a development well into the offshore Frade field in late 2011. Soon, an oil slick appeared on the surface of the water. About 2,400 barrels of oil had escaped through the well bore, seeped up into the rock, then escaped through fissures in the seafloor.

Chevron installed gear to trap the oil. What little of the 2,400 barrels that it didn’t manage to capture floated out to sea and dissipated. There are no lasting signs of environmental damage.

But the event became a circus in Brazil. Black ink was thrown outside Chevron’s office in Rio. Passports were confiscated. Carlos Minc, the environmental secretary of Rio state, reportedly said, “I want to see the CEO of Chevron swim in that oil.” A Brazilian prosecutor sued Chevron for $22 billion in damages, an amount that Petrobras, which owns 30 percent of the field, called unreasonable.

No one paid much attention several months later when Petrobras announced that it had discovered similar leaks in a couple of its own offshore fields. In December, Chevron offered to settle with the Brazilian government for $150 million, an amount that Watson says “seemed commensurate with what transpired”.

In Nigeria in January 2012, the KS Endeavor jack-up rig was drilling a high-pressure gas well six miles off the coast. The drillers lost control and the well blew out, igniting the rig in a fireball that burnt for days and killed two workers. Thankfully, because the reservoir was almost entirely gas, there was little environmental damage. Nigeria reportedly wants Chevron to pay $3 billion for the accident, though the company says it hasn’t been formally notified of any such fine.

How is it possible after BP’s disaster in the Gulf of Mexico that Chevron could suffer these drilling accidents? “I preach introspection,” says Watson. “We make sure we can learn from every incident that happens, so that we don’t get complacent, we don’t get arrogant, and we work to get better every day. We didn’t put that all together in Nigeria.” It will cost them.

—CH

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)