Star Citizen: The most expensive video game ever made

Chris Roberts has spent seven years and raised nearly $300 million—most of it from average gamers—building Star Citizen. It's on pace to be the costliest video game ever made and—outside of cryptocurrency—the world's largest crowdfunded project. It's still not ready. It may never be

At his Los Angeles studio, Cloud Imperium Games co-founder Chris Roberts stands in front of the rendering of one of the worlds he has created for his colossal, incomplete video game, Star Citizen

At his Los Angeles studio, Cloud Imperium Games co-founder Chris Roberts stands in front of the rendering of one of the worlds he has created for his colossal, incomplete video game, Star CitizenImage: Ethan Pines for Forbes

It’s October 2018 and 2,000 video game fanatics are jammed into Austin’s Long Center for the Performing Arts to get a glimpse of Star Citizen, the sprawling online multiplayer game being made by legendary designer Chris Roberts. Most of the people here helped to pay for the game’s development—on average, $200 each, although some backers have given thousands. An epic sci-fi fantasy, Star Citizen was supposed to be finished in 2014. But after seven years of work, no one—least of all Roberts—has a clue as to when it will be done. But despite the disappointments and delays, this crowd is cheering for Roberts. They roar as the 50-year-old Englishman jumps onto the stage and a big screen lights up with the latest test version of Star Citizen.

The demo starts small: Seeing through the eyes of the in-game character, the player wakes up in his living quarters, gets up and brews a cup of coffee. Applause quickly turns to laughter when the game promptly crashes. While his underlings scramble to get the demo running again, a practiced Roberts smoothly fills minutes of dead air by screening a commercial for the Kraken, a massive war machine spaceship. Eventually the Kraken, like all the starships that Roberts sells, will be playable in Star Citizen. At least that’s the hope. But for $1,650 it could be yours, right away.

“Some days, I wish I could be like... ‘You’re not going to see anything until it’s beautiful’,” Roberts later says at his Los Angeles studio. “A lot of times we’ll show stuff and literally say, ‘Now, this is rough’.”

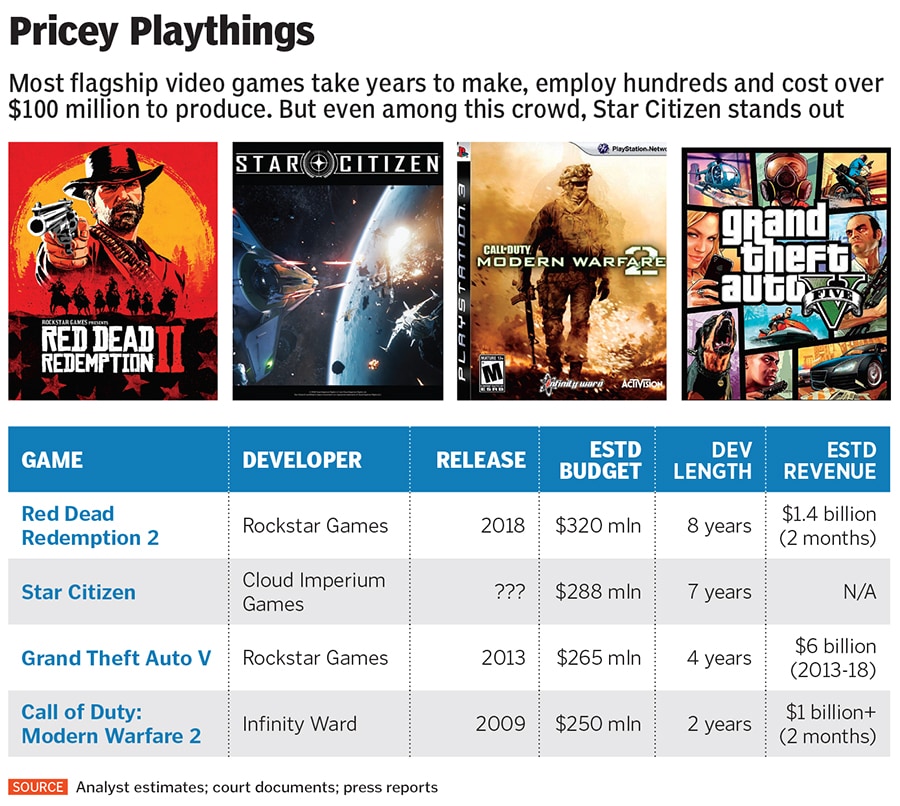

What’s really rough is the current state of Star Citizen. The company Roberts co-founded, Cloud Imperium Games, has raised $288 million to bring the PC game to life along with its companion, an offline single-player action game called Squadron 42. Of this haul, $242 million has been contributed by about 1.1 million fans, who have either bought digital toys like the Kraken or given cash online. Excluding cryptocurrencies, that makes Star Citizen far and away the biggest crowdfunded project ever.

Rough playable modes—alphas, not betas—are used to raise hopes and illustrate work being done. And Roberts has enticed gamers with a steady stream of hype, including promising a vast, playable universe with “100 star systems”. But most of the money is gone, and the game is still far from finished. At the end of 2017, for example, Roberts was down to just $14 million in the bank. He has since raised more money. Those 100 star systems? He has not completed a single one. So far he has two mostly finished planets, nine moons and an asteroid.

This is not fraud—Roberts really is working on a game—but it is incompetence and mismanagement on a galactic scale. The heedless waste is fuelled by easy money raised through crowdfunding, a Wild West territory nearly free of regulators and rules. Creatives are in charge here, not profit-driven bean counters or deadline-enforcing suits. Federal bureaucrats and state lawyers have intervened only in a few egregious situations where there was little effort to make good and a lot of the money was pocketed by the promoters. Many high-profile crowdfunded projects, like the Pebble smartwatch ($43.4 million raised) and the Ouya video game console ($8.6 million), have failed miserably.

If you don’t play video games, you probably have never heard of Roberts. But in the world of consoles and controllers, he is Keith Richards: An ageing rock star who can still get fans to reach into their pockets. Roberts first gained fame with his early 1990s hit Wing Commander, a space combat series that grossed over $400 million and featured Hollywood stars like Mark Hamill and Malcolm McDowell. He followed that success by starting his own studio, Digital Anvil, with Microsoft as an investor. There, he spent years working on Freelancer, a spiritual successor to Wing Commander, which was eventually released years behind schedule and was far from a blockbuster. Roberts also dabbled in Hollywood, spending tens of millions on a movie version of Wing Commander that he directed himself and that was a critical and commercial flop.

Forbes spoke to 20 people who used to work for Cloud Imperium, many of whom depict Roberts as a micromanager and poor steward of resources. They describe the work environment as chaotic.

“As the money rolled in, what I consider to be some of [Roberts’s] old bad habits popped up—not being super-focussed,” says Mark Day, a producer on Wing Commander IV who runs a company that was contracted to do work on Star Citizen in 2013 and 2014. “It had got out of hand, in my opinion. The promises being made—call it feature creep, call it whatever it is—now we can do this, now we can do that. I was shocked.”

“There is a plan. Don’t worry—it’s not complete madness,” Roberts insists.

But what Roberts has stirred up does seem crazy. Star Citizen seems destined to be the most expensive video game ever made—and it might never be finished. To keep funding it and the 537 employees Cloud Imperium has been working in five offices around the world, Roberts constantly needs to raise more money because he is constantly burning through cash.

Up to a point, Roberts has been transparent about where the money has been going. He released years’ worth of financial statements last December. But he won’t say how much he or other top Cloud Imperium execs have made from the project. His wife and his brother both work in senior positions at the company.

“There’s no two ways about it, man. Star Citizen is nuts,” says Jesse Schell, a prominent game developer and professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “This thing is unusual in about five dimensions... it is very rare to be doing game development for seven years—that’s not how it works. That’s not normal at all.”

In the fall of 2012, Chris Roberts stepped onto the stage of a different Austin auditorium and proclaimed, “I’m coming back.” With a sleek video showing flying spaceships and a short demo he played from the podium, Roberts announced his first crowdfunding campaign, which quickly raised $6.2 million. It doesn’t seem like a lot in a world where budgets for quality games can easily reach into the tens of millions, but Roberts left the impression that it would be enough. After all, Star Citizen was already “12 months into production”. It seemed like a redemption song from a man who had been out of gaming for a decade after his partnership with Microsoft had gone sour. (Today, Roberts says that initial year of development doesn’t count because “it was more proof-of-concept work”.)

Growing up in Manchester, England, Roberts was a skilled coder with grand ambitions. He made games in his teens, including a soccer simulation for the BBC Micro, before landing in Austin in 1987. There, he met influential video game director Richard Garriott—famous to fans of the blockbuster Ultima series as Lord British—and at age 19 started working for Garriott’s Origin Systems, where Roberts created Wing Commander. The PC game launched in 1990 and was wildly successful.

In 1996, Roberts left Origin and co-founded Digital Anvil to create games in partnership with Microsoft, which was beginning to take gaming seriously and had a minority stake. Following the success of Wing Commander, Roberts authored another game at Origin, Strike Commander, known for its production headaches, and developed a reputation as an exacting boss. But he was still seen as gaming’s golden boy.

Roberts expanded on the idea of a living, breathing universe when he announced Freelancer in 1999, two years after the start of development. At the same time, Roberts convinced 20th Century Fox to back a $30 million movie version of Wing Commander, which lost nearly $20 million. Stuart Moulder, the Microsoft general manager who oversaw the software giant’s relationship with Digital Anvil, came to believe that Microsoft money intended for game development was instead used for the movie. “[Roberts’s] energy and attention and some of the funds were siphoned off for that movie,” Moulder says. “The Digital Anvil investment has to be looked at as largely a failure.”

Roberts concedes that Microsoft was frustrated with the time he spent on the movie but says funds used for it were appropriate because they came from Microsoft’s purchase of the minority stake, with the proceeds earmarked for general business purposes that included moviemaking. Either way, Microsoft acquired full control of Digital Anvil in 2001, and Roberts left the company. It would be another two years before Freelancer hit stores as a much smaller game than envisioned.

Free of Microsoft, Roberts went full Hollywood. He got in on the business side of things by co-founding production company Ascendant Pictures, which made several mostly forgettable movies like Outlander (2008) and The Big White (2005). Roberts got a producer credit on Ascendant’s most successful film, Lord of War, starring Nicolas Cage.

But things were shaky. To make the movies, Roberts teamed up with a German lawyer, Ortwin Freyermuth, who is now the vice chairman of Cloud Imperium. They arranged financing from an investment fund that was using a tax scheme to raise money in Germany for Hollywood movies. By 2006, the German government had sentenced the fund’s founder to jail for tax fraud, according to Variety. Roberts and Freyermuth were not implicated.

With the German money dried up, things were bleak in Tinseltown. Kevin Costner sued Ascendant Pictures at the end of 2005, claiming it reneged on a deal to pay him $8 million to act in a comedy. (Ascendant denied wrongdoing and the suit was settled.) Roberts sold Ascendant Pictures in 2010 to a small production company called Bigfoot Entertainment, which had offices in Los Angeles and the Philippines.

Roberts’s Hollywood days were over. It was time to get back to gaming.

On a summer Saturday in 2007 a trespasser slipped by a security gate and entered Chris Roberts’s Los Angeles (LA) home. Inside, Madison Peterson, Roberts’s former common-law wife, with whom he had a long on-and-off relationship, was startled and feared her young daughter could be harmed or kidnapped. Peterson later identified the trespasser as Sandi Gardiner, who is now Roberts’s wife (for the second time) and a co-founder of Cloud Imperium. Roberts reported the incident to the police, and a California judge issued a temporary restraining order that required Gardiner to stay 100 yards away from Peterson, who claimed in her temporary restraining order application that Gardiner had been stalking and threatening both her and her daughter for nearly three years.

“Ms Gardiner has an unnatural and irrational fascination with my daughter and me,” Peterson wrote. “I constantly and continually look to make sure my daughter and I are not watched.”

In a court-filed declaration he signed at the time, Roberts said Gardiner had also visited Peterson’s San Diego home and once became violent and tried to strangle him. “I believed that if she had a gun she would have killed me,” Roberts said in the declaration. “I believe that Ms Gardiner is not emotionally stable.” After three months, the restraining order was dissolved. Today, Roberts says he cannot recall signing the declaration and that what is ascribed to him in the court filings was prepared by Peterson and false. Despite the documentation, Gardiner flatly denies the incidents took place.

A few years later, Roberts co-founded Cloud Imperium with Gardiner and Freyermuth, his lawyer partner from Hollywood. He had remarried Gardiner in 2009. Their first marriage was annulled in 2005, court records show. An actor who is still trying to make it in Hollywood, the 43-year-old Australia-born Gardiner is also Cloud Imperium’s head of marketing and a driving force behind the company’s fundraising.

The initial 2012 crowdfunding campaign was successful, but it turned out that $6.2 million wasn’t nearly enough to feed Roberts’s ambitions. But Roberts and Gardiner came up with an ingenious way to keep raising funds: They would sell spaceships—hundreds of thousands of them.

Star Citizen has gigantic ships and tiny ships, exploration ships and cargo ships, refuelling ships and mining ships, heavy fighters, light fighters, medium fighters, snub fighters, destroyers, gunships and many, many more. By Forbes’s count, Cloud Imperium has sold 135 different spaceship models for as much as $3,000 apiece. Eighty-seven of these ships have been completed to the point that players can fly them in the buggy early versions of Star Citizen; some of the other 48 ships seem like little more than fancy images.

“Nobody is obligated to buy more than just the starter ship,” says Gardiner. “All of the marketing is done by the fans virally, and a lot of those ships are because the community has asked for them.”

“[The] marketing of the game has been an objective success, as we’re the most crowdfunded anything, [and it] was overseen by Sandi,” Roberts says.

To supercharge the money that Gardiner was raising, Roberts brought in a big outside investor for the first time last fall. Cloud Imperium received $46 million from Clive Calder, the South African billionaire behind Jive Records, and his son, Keith. The funds are meant for—what else?—more marketing.

Cloud Imperium has churned out new versions of ships it has already sold and allows players to trade in their old ships to help buy new ones. The company also introduced the concept of “warbonds”, selling ships at a discount if new cash is used to purchase them. Players gain elite concierge club status by spending $1,000 (High Admiral) or $10,000 (Wing Commander). High-status players get bonus items like the “arclight II laser pistol executive edition” or a digital bottle of space whiskey.

It may seem silly, but there are real victims. Ken Lord is a 39-year-old data scientist from the Denver area, who suffers from worsening multiple sclerosis. Lord first backed Star Citizen in 2013 and eventually spent $4,500 buying spaceships. Last year, Lord unsuccessfully sued Cloud Imperium for a refund. “You take something that is bad, like spending too much money on a video game, and turn it into a socially exclusive club and make it desirable—cheers to their marketing department,” he says. (Bizarrely, Lord, who claims to have “poor impulse control”, continued to buy more spaceships after his lawsuit failed.)

“It’s not my place to talk about what people spend their money on,” says Gardiner.

When asked what it was like to work at Cloud Imperium, one former senior game maker who left in 2018 messaged a link to the Spinal Tap movie scene with an amplifier volume knob turned to 11. Former employees say Roberts gets involved in the smallest details and pushes huge and complex investments in areas that are not worth the effort. At one point, one of the company’s senior graphics engineers was ordered by Roberts to spend months, through several iterations, getting the visual effects of the ship shields just right. In addition, workers have had to spend weeks on end making demos so that Cloud Imperium can keep selling spaceships—and raising more money.

Before David Jennison quit as Cloud Imperium’s lead character artist in 2015, he wrote a letter to human resources—it leaked on the internet—trying to explain why he completed only five characters in 17 months. One problem, Jennison said, was that Roberts frequently reversed approvals for the characters he was working on. “All the decisions for the character pipeline and approach had been made by Roberts,” Jennison wrote. “It became clear that this was a companywide pattern—CR dictates all.”

A company spokesman retorts: “It does say ‘Chris Roberts’ on the box, so one would naturally expect him to be quite involved with decision-making.”

As in the past, Roberts also seems super-focussed on the blockbuster-movie aspect of his game. Cloud Imperium hired a large and presumably expensive cast, even by today’s gaming standards, including Gary Oldman, Mark Hamill, Gillian Anderson and several other prominent actors, and flew them to London. There Roberts personally directed them for Squadron 42 in a motion-capture studio built by actor Andy Serkis. Gardiner also joined the cast.

Roberts set the release date for Squadron 42 in the fall of 2015, with a full commercial version of Star Citizen coming in 2016. Roberts now says a beta version of Squadron 42 will come out in 2020 and has stopped trying to guess when Star Citizen will happen. But the footage of Oldman and Hamill in their motion-capture suits has already proved useful, making its way into promotional videos. “Having a cinematic story with big actors is what people expect from me,” Roberts says.

The Federal trade commission has received 129 consumer complaints related to Cloud Imperium, involving requests for refunds as high as $24,000, according to information revealed by a Freedom of Information Act request. “The game they promised us can’t even barely run. The performance is terrible and it’s still in an ‘Alpha’ state,” complained a Florida resident who claimed last year to have spent $1,000. “I want out. They lied to us.”

Cloud Imperium says its policy of granting refunds to fans who make requests within 30 days is fair, adding that the company is being transparent about its game development. Even though not a single one of the 100 promised star systems has been finished, Roberts says Cloud Imperium has built tools that will expedite the building of future planets and moons, and claims the first star system will be the largest and most complex. For now, fans pay $45 for an introductory ship and access to what has been built, and the backers have something in their hands. Calling it a game is a stretch, but that doesn’t stop Roberts.

“Star Citizen is a playable game,” Roberts insists. “It has more functionality and content than a lot of finished games.” He adds that 40,000 people played the game together online over a recent week and that criticism of Cloud Imperium’s development work is fuelled by online trolls. There are many believers. “I have complete faith,” says Dan Paulsen, a backer of Star Citizen since 2016. “If there’s a delay, it’s for a good reason. It’s because they want it to be a better project.”

Last year Cloud Imperium released financials that showed its biggest expense was annual salaries of $30 million. But the documents did not detail how much Roberts and Gardiner have been paid over the years. In September 2018, the Roberts Family Trust, with Gardiner as its trustee, purchased a house for $4.7 million in LA’s Pacific Palisades neighbourhood. Prior to that, Roberts had been renting. Roberts says he sold his Hollywood house in 2007 because he wanted to experience living near the ocean. He then rented for ten years because he wasn’t sure if he would like it or stay in LA long-term.

“I was quite successful before I founded Cloud Imperium,” Roberts says, adding that he was a partner at Origin, which EA bought in 1992 for $37 million, and that he was paid as the majority owner of Digital Anvil when Microsoft acquired it. Roberts has emphatically said he is not lining his pockets from Cloud Imperium and that the company’s fundraising is ethical. Roberts says he is compensated like a typical C-suite game executive.

“I know everyone thinks we just have $200 million in the bank and we dive off into it like Scrooge McDuck or something,” he says, and points out that many players view Star Citizen as a hobby they spend money on, like golf. “All I know is when people come to me, I say, ‘Look, you don’t need to spend anything more on this game than $45’.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)