Stewart and Lynda Resnick: America's nuttiest power couple

Fresh off sapping the water from a Pacific island and flogging pomegranate juice with questionable health claims, Stewart and Lynda Resnick, the billionaire couple behind Fiji Water and POM Wonderful, are profiting off pistachios and almonds with the same combination of marketing genius and opportunistic water grabs amid California's worst drought on record

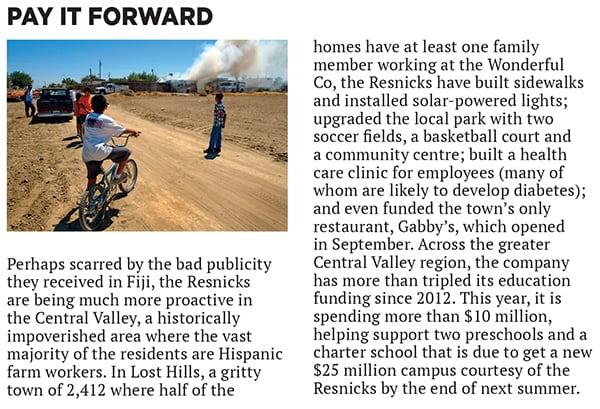

For over four years a record-breaking drought has scorched central California with Old Testament cruelty. Drive west of Bakersfield into the heart of the San Joaquin Valley and soon you will be engulfed by sloping brown hills broken up by dusty, slate-coloured fields. Desolate little towns off the highway dot the parched landscape. Lost Hills (population 2,412) consists largely of a tamale shack, a mostly empty James Dean-themed shop, a dilapidated tyre store and a rundown pool hall.

Yet, there is an Eden. It’s a little to the west of Lost Hills, off Route 33. Here there are rows upon rows of green—some 70,000 lush acres of water-hungry pistachio and almond trees. Come at the right time of the year, and you’ll see the almond trees blossoming, covering the valley in a blanket of light pink petals. This land belongs to the billionaire Resnicks, Stewart, 77, and Lynda, 72. It’s the most valuable part of their $4.3 billion fortune. Those crops and the land are worth more than ever before, about $3 billion.

Their oasis has plenty of water, the result of relentless opportunism that has given their orchards access to more water than nearly any other farm during the worst drought on record in California’s history. The Resnicks use at least 120 billion gallons a year, two-thirds on nuts, enough to supply San Francisco’s 852,000 residents for a decade. They own a majority stake in the Kern Water Bank, one of California’s largest underground water storage facilities, which they got fairly but sagely from the government 20 years ago. It is capable of storing 500 billion gallons of water. They have also spent at least $35 million in recent years buying up more water from nearby districts to replenish their supplies.

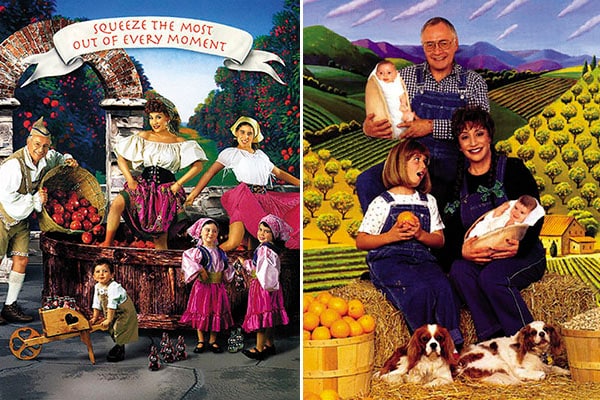

The Resnicks, who live in a nine-bedroom mansion in Beverly Hills and fly into the valley about once or twice a month, are crafty dealmakers and even finer marketers. In addition to the pistachios and almonds, their company, renamed Wonderful in June, owns 32,000 acres of California citrus, flower-delivery service Teleflora, POM Wonderful pomegranate juice and Fiji Water, which collectively brought in $3.8 billion in sales last year. By their own estimates, almost half of American households buy their products.

Not everyone is eager to fill their pantry with a Resnick brand. Agriculture’s king and queen have a history of commandeering natural resources in pursuit of profit, and their actions in Fiji—where they annually fill millions of plastic bottles with water and then ship them thousands of miles across the world while residents haven’t always had access to potable water themselves—have already infuriated environmentalists. Now they are being vilified in California for their water use in the ongoing drought. “Ninety-nine percent of us are being asked to take cuts for the one percent: Stewart Resnick,” says Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla, executive director of Restore the Delta, a Stockton, California-based non-profit working to protect fisheries and farms in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

It’s a wonderful life: The Resnicks’ fields (in green) and those of their neighbours near Lost Hills, California

Several anti-Resnick forces allege the couple’s immense water supply is ill gotten. The Kern Water Bank and Westside Mutual Water, a company set up to control the Resnicks’ water, have been sued three times since 2010. The water lawsuits—one reached an interim settlement, one led to environmental review and one is on appeal—have alleged that the Resnicks had no ownership right to the water bank and that the bank is dipping into their neighbours’ water supply.

The Resnicks deny the allegations and say they are legally and morally in the right. “I don’t even know what these are about, because my view is we’re going to win,” says Stewart Resnick. “We’ve been sued over the same thing over and over and continue to win. If I had a son who, god forbid, should go to law school, I would say go into water law. You get one lawsuit that lasts 20 years.” He says that he simply invested in the storage facility at an opportune time and also cites the $25 million the company has spent on irrigation systems that reduce the use of water by dripping it directly on the roots rather than using sprinklers to flood the fields. Even with these water-saving measures, he says, Wonderful expects production of the superthirsty almond trees to drop by 20 percent and pistachios to drop by 60 percent this year. (It takes one gallon to produce just one almond or one pistachio.)

“When I first came to California 60 years ago, I should have bought property on Rodeo Drive. Now I would like to go back and buy the property on Rodeo Drive for the same price it was 60 years ago,” says Resnick. “People that had opportunities to buy into the water bank—just like we did—didn’t do it. Now they think it’s worthwhile.”

The Resnicks miss few opportunities. The son of a New Jersey bar owner who drank and gambled away his money, Stewart transferred in 1955 from Rutgers to UCLA. To make ends meet, he started a janitorial business while in college. By the time he graduated, he had ten employees. He continued to operate the business while in law school and eventually employed 100 people.

By contrast, Lynda grew up in Beverly Hills, the daughter of a wealthy Hollywood film producer, with two Rolls-Royces in her driveway. A former child actress who performed on a weekly variety show, she dropped out of Los Angeles City College and founded an advertising agency at 19; she married that year and had three children before divorcing just as the business started to struggle. More troubles came when she began dating a man whose friend asked if he could use her copier at night and on weekends. She denies realising that his friend Daniel Ellsberg was printing what would later be known as the Pentagon Papers, but she eventually got entangled in legal proceedings with the federal government. (In the end, she was subpoenaed but never charged.)

The Resnicks met in 1970 when Stewart came looking for marketing help for the janitorial business. He led her on, and after several meetings, she bluntly asked whether she was going to get the account or not. Also divorced with children, he told her that he wanted to start a relationship instead. They married and in 1979, bought Teleflora, a failing flower-delivery service.

Theirs was a symbiotic partnership from the outset: He was level-headed and finance-minded; she was more dramatic with notable marketing flair. The combination has proved unstoppable. Stewart bought his first parcel of farmland in California’s Central Valley in 1978 as a hedge against inflation. Lynda then took the fruits and nuts of their labour and marketed the heck out of them. “It takes a nut to sell a nut,” she would later say. Lynda branded mandarins as Cuties and then, after a falling-out with a partner, rebranded them as Halos. She marketed pomegranate juice as POM Wonderful, a magical elixir filled with antioxidants. (Stewart, who survived prostate cancer, drinks eight ounces of POM Wonderful and takes a pomegranate pill every day and says that he hasn’t had a cold in a decade. At 77, he cycled about 40 miles a day across Italy during a nine-day bike trip this summer.) In 2009, came the “Get Crackin’” ad campaign marketing their pistachios and, in 2013, 15-second clips hit the Super Bowl, with recent spots featuring late-night host Stephen Colbert. (“I can’t make anyone cry in 15 seconds, but we can make them laugh,” says Lynda, adding that 30-second ads in the Super Bowl were too expensive.)

Undoubtedly aided by Stewart’s law degree, the Resnicks have also proven to be adept at fighting legal battles. Their mail-order collectibles firm, Franklin Mint, was sued in 1998 by the estate and charitable foundation of Princess Diana, which said the firm did not have the right to use and profit from her image on keepsakes; Franklin Mint filed a countersuit in November 2002, alleging it was the victim of an ugly smear campaign. In 2011, five years after they sold Franklin Mint, a settlement was reached. The Resnicks were paid $50 million, all of which they donated to charity.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed a complaint in 2010 that the Resnicks’ POM Wonderful had used deceptive advertising when marketing the antioxidant-rich drink as being able to treat, prevent or reduce the risk of heart disease, prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction. In 2012, a federal judge agreed that some of the ads were misleading. In 2013, FTC commissioners denied the Resnicks’ appeal. In October 2015, the Resnicks asked the Supreme Court to take the case.

The Supreme Court sided with the Resnicks in a separate case. In that instance, POM Wonderful sued Coca-Cola, which sold pomegranate blueberry juice under the Minute Maid brand, alleging that it shouldn’t be able to market drinks with just 0.3 percent of actual pomegranate juice. In 2014, the court ruled that Wonderful could proceed with its case. Coca-Cola has denied its labels were misleading. That trial is slated for next year. Meanwhile, POM is spending millions on research to show the benefits of eating pomegranates, and expects to release positive results based on human trials.

Regarding their water business in Fiji, they have been vilified as greedy capitalists for hogging the archipelago’s precious water supply. They bought Fiji Water in 2005 and started pumping out and bottling millions of pricey water bottles from a pristine aquifer. Meanwhile, island natives didn’t always have water to drink themselves, due to crumbling and insufficient infrastructure. The Resnicks’ once friendly relations with the volatile Fijian military junta turned sour in 2010, when the government announced a tax hike on the company, which leases the land and is one of the island’s biggest employers. The Resnicks shut down operations temporarily before agreeing to pay the reported 45 percent tax increase on each litre of water. Today, Fiji Water operates three bottling production lines, up from one a decade ago, and last year shipped more than 250 million bottles worldwide, an eightfold increase since buying the business. It is the bestselling imported water brand in the US. The Resnicks, who visited the island this summer, say they are working to help locals access safe drinking water by investing $600,000 in water infrastructure for 77,600 people. They also say they donated $5 million to rainforest conservation and other initiatives.

Fijian military dictators aside, the couple knows the value of cultivating powerful friends, whether at their Los Angeles mansion or their Arts & Crafts lodge in Aspen, where they spend several months a year. In 2000, when the Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, the Resnicks hosted a cocktail party honouring Senator Dianne Feinstein at their sprawling estate in Beverly Hills, attended by then California governor Gray Davis and former US President Jimmy Carter.

Other guests through the years have included: Arianna Huffington, junk bond billionaire Michael Milken, Tesla CEO Elon Musk, Yahoo News anchor Katie Couric and even the odd Supreme Court justice. “It’s a who’s who of politics and media and celebrity. It’s almost like old-fashioned salons, where [Lynda] can bring people together,” a former executive and regular guest says.

It’s in the Central Valley where they now have their biggest fight. Stewart first bought land in the area as an investment in the 1970s. Over the next decade, he picked up tens of thousands more acres. When a six-year drought started in 1987 and cost local farmers $800 million, he had much less skin in the game. Still he took note, quickly realising that the contracts he had with the state, which delivered water from the California Aqueduct—a 444-mile-long channel flowing with runoff from the snow-capped Sierra Nevada mountains—were vulnerable when water was scarce and the state couldn’t meet everyone’s needs.

In what some critics have called secret meetings, some of his most trusted advisors met with leaders from southern California water districts and state water officials, helping broker a sweetheart deal in 1994. Two decades later, it still gives the Resnicks nearly unrivalled access to water. Wonderful denies the meetings were done clandestinely, alleging that those who say so have an “axe to grind”. The upshot of that meeting: California handed over public land and an underground aquifer (former farmland and oilfields that had the potential to store about 500 billion gallons of water) to five public water districts and the Resnicks’ Westside Mutual Water Co. The new owners agreed to forfeit state water contracts. They then installed a six-mile-long canal and 85 wells at a cost of $50 million. Forbes estimates that the Resnicks’ 57 percent stake in the storage facility is worth at least $250 million.

But their ownership has been under siege, challenged in court nearly continuously for the past two decades. In 2010, the Center for Biological Diversity, a nationwide environmental non-profit group based in Arizona, and several other groups sued the bank and its members, including Westside and the Resnicks’ parent company. A Sacramento County Superior Court judge ruled last year that the state gave up the water resources without properly analysing the potential environmental impacts but dismissed three other allegations—including one challenging the agreement’s constitutionality. The case is now being tried in Sacramento’s Third District Court of Appeal. “We’re warriors out here trying to make sure that a bunch of fat cats don’t suck this state dry,” says Adam Keats, chief lawyer for the opposition, who adds that the Resnicks’ lawyers have “a level of rabidness in protecting their fortunes. They are fiercely defending that golden goose”.

In the second suit brought on by those two water districts and two others, Kern Water Bank leaders agreed under a settlement to assess damages and, if necessary, compensate the affected landowners.

The Resnicks are already looking to secure additional water sources. The couple could score big if a $15 billion water project championed by Governor Jerry Brown is officially approved in the next few years. At least two Wonderful farming executives are involved in a grassroots push for the project, now called California WaterFix, which would carry water from the Sacramento River Delta through two 30-mile-long tunnels to San Joaquin Valley farms.

There’s another cushion they’ve been building for decades. They have invested $100 million in technology initiatives designed to help manage water shortages and high utility costs; their water expenses, which tripled in the past 15 years, account for 40 percent of their agricultural costs. “There’s no bigger incentive. We have a very aggressive R&D programme,” Stewart says. In addition to drip irrigation systems now used on all their farms, they have spent $22 million on solar energy networks and $41 million on fuel-cell research and implementation to power their plants and facilities more cost effectively. A new research project is also about to roll out “supertrees” cultivated to yield more with a regular tree’s amount of water, which could even be sold to rival farmers. Whatever the future brings, it would probably be a mistake to bet against the power couple.

“You have to be an optimist to be a farmer. Fortunately, with our management team, we have some optimists and some pessimists,” Stewart says. And, of course, some opportunists.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)