The $100 Billion Man: How LVMH's Bernard Arnault stitched together a giant fortune

With Louis Vuitton, Dior and 77 other brands, Arnault has created the world's largest luxury empire. Now, he's looking to scale up

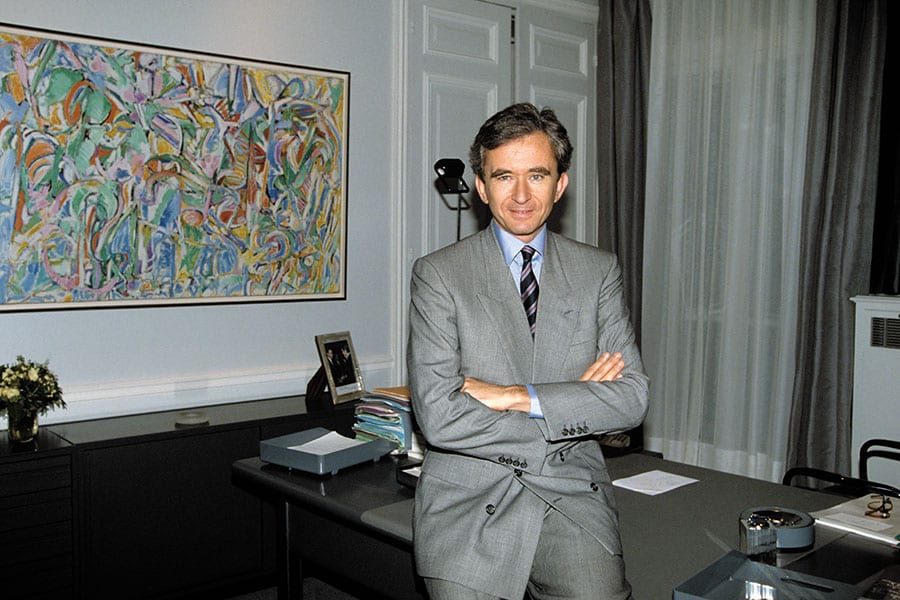

Image: Jean-Claude Deutsch/Paris Match via Getty Images

Image: Jean-Claude Deutsch/Paris Match via Getty Images

Bernard Arnault inspires me,” says Sheron Barber.

The 38-year-old has traveled from Los Angeles to the palatial Louis Vuitton store on Paris’ Place Vendôme during the height of fall Fashion Week to pay tribute to his idol, the head of luxury colossus LVMH. Barber is a spectacular sight. He has dyed black dollar signs in his close-cropped fuchsia and yellow hair, a green grill covering his teeth and multiple Louis Vuitton luggage locks dangling from the stainless-steel chain encircling his neck. “I spent a couple hundred thousand last year on LV,” he says. He earns a handsome living customising the looks of music acts like Migos and Post Malone. In his latest video, ‘Saint-Tropez’, Post Malone wears a chest plate constructed by Barber that is a blend of black leather and a Vuitton bag. Of Arnault, Barber declares: “He has single-handedly defined modern luxury.”

“It’s a most exceptional Louis Vuitton maison,” Arnault says of the Place Vendôme store, in English with a distinct French accent. “You can see the entire universe of the brand.” Opened two years ago, the space feels like a cross between a museum and a private club. An array of Vuitton’s wares are displayed inside gleaming vitrines and on artfully placed shelves. Marble staircases with glass balustrades lead to a private atelier on the fourth floor where six seamstresses create bespoke dresses for celebrities like Lady Gaga and Emma Stone. “I was very involved in the design,” Arnault says.

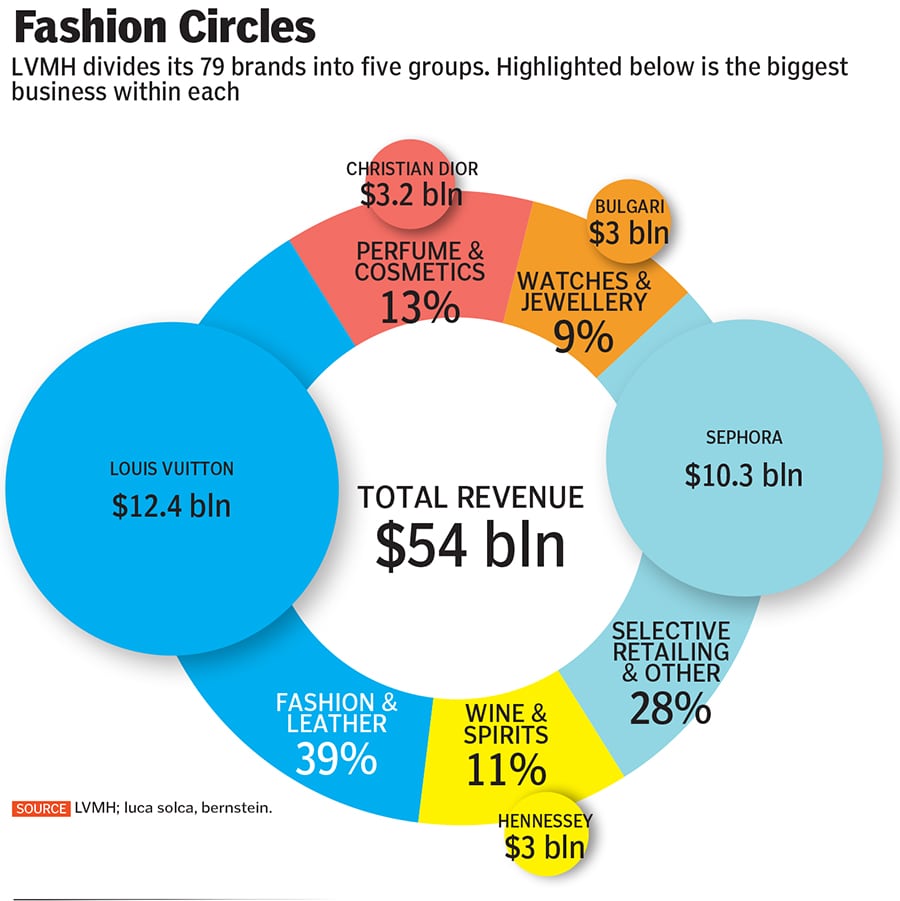

He obsessively tracks his top brands, especially Louis Vuitton, the conglomerate’s cash machine, which accounted for nearly a quarter of LVMH’s 2018 revenue of $54 billion and up to 47 percent of profits, according to analysts. (LVMH shares financials for its top five divisions but not for its individual brands.) Vuitton’s selection of bags, apparel and accessories, which the company never wholesales or discounts, is an ever-changing mixture of classic and contemporary, like an $8,600 limited-edition twist on its Capucines purse in turquoise leather with an appliqué pattern designed by Tschabalala Self, a 29-year-old artist from Harlem. American Virgil Abloh, 39, Vuitton’s new menswear designer, created a stir early this year when he debuted a collection with glow-in-the-dark bags that use fiber optics to illuminate the LV logo in the colours of the rainbow.

“Why are brands like Louis Vuitton and Dior so successful?” Arnault asks. “They have these two aspects, which may be contradictory: They are timeless, [and] they are at the utmost level of modernity. . . . It’s like fire and water.”

The Louis Vuitton store on Paris’s Place Vendôme pays homage to the brand’s founder, who opened his first shop nearby in 1854

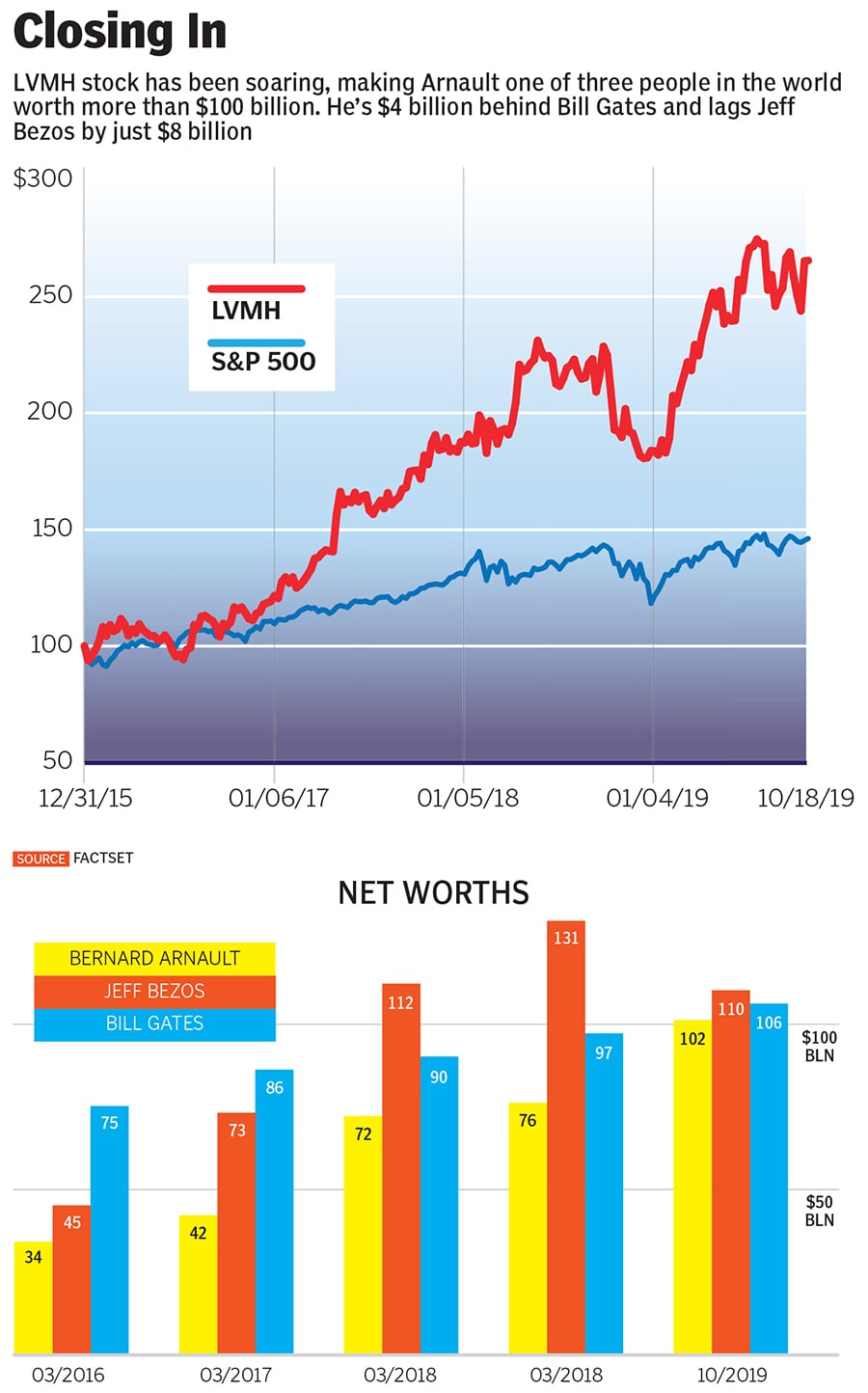

That paradox has translated into record sales and profits at LVMH, whose roster of more than 70 brands includes Fendi, Bulgari, Dom Pérignon and Givenchy. That, in turn, has helped drive up LVMH’s stock price, which has nearly tripled in less than four years. Arnault, who owns 47 percent of the company’s shares with his family, is now worth $102 billion, $68 billion more than he was in 2016. He is the third-richest person on earth, just behind Jeff Bezos ($110 billion) and Bill Gates ($106 billion).

And at 70, Arnault is far from done. In late October, LVMH made an unsolicited $14.5 billion bid for the 182-year-old American jeweller Tiffany. If the deal goes through, it will be Arnault’s biggest acquisition ever. “If you compare us to Microsoft, [we are] small,” he says. Indeed, LVMH’s market value of $214 billion lags far behind the software giant’s $1.1 trillion. “It’s just the beginning,” says Arnault.

*****

Arnault’s beginnings in France’s industrial north were far removed from the glittering perch he now occupies. His first love was music, but he didn’t have the talent to make it as a concert pianist. Instead, after graduating from an elite French engineering school in 1971, he joined his father at the construction firm founded by his grandfather in the city of Roubaix.

An exchange with a New York cab driver that same year planted a seed that would grow into LVMH. Arnault asked the cabbie if he knew of France’s president, Georges Pompidou. “No,” replied the driver, “but I know Christian Dior.”

At age 25, Arnault took charge of the family business. After socialist François Mitterrand became France’s president in 1981, Arnault moved to the States and tried to build a division there. But his ambitions were bigger than construction. He wanted an enterprise he could scale, a business with French roots and international reach.

In 1984, when he learned that Christian Dior was for sale, he pounced. Its parent, a textile and disposable-diaper company called Boussac, had gone bankrupt, and the French government was looking for a buyer. Arnault put up $15 million of his family’s money, and Lazard supplied the rest of the $80 million purchase price. At the time, according to reports, he made a pledge to revive operations and preserve jobs, but instead he fired 9,000 workers and pocketed $500 million, selling off most of the business. Critics recoiled at his brazenness, which seemed more American than genteel French. The media later dubbed Arnault “the wolf in the cashmere coat”.

Arnault’s next prey was Dior’s perfume division, which had been sold to Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy, and a fight between the company’s brand heads gave him an opening. First, he teamed up with the boss of Vuitton, the leather goods company whose founder had made custom trunks for Empress Eugénie, the wife of Napoleon III. Arnault helped the head of Vuitton oust Moët’s chief, only to get rid of him, too. By 1990, again backed by Lazard and using the cash from Boussac, he had taken control of the company, which included Moët & Chandon, the famous French champagne maker, and Hennessy, the French cognac producer that dates to 1765.

After conquering Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy, Arnault spent billions to acquire leading European companies in fashion, fragrance, jewellery and watches, and fine wines and spirits. Since 2008, LVMH has purchased 20, bringing the total to 79 brands. In 2011 it paid nearly $5 billion for the Italian jeweller Bulgari in a mostly stock deal. Two years later it bought the fine-wool purveyor Loro Piana for a reported $2.6 billion. Arnault’s most recent acquisition was in April when LVMH paid $3.2 billion for the London-based hotel group Belmond, whose opulent holdings include the Cipriani hotel in Venice, the luxury train line Orient Express and three ultra-luxe safari lodges in Botswana.

“Bernard Arnault is a predator, not a creator,” says a banker who was close to the Boussac deal.

Arnault has not succeeded at every conquest. In 2001 he lost what the media called the “handbag war” for control of fabled Italian fashion house Gucci, to his French luxury rival, François Pinault. Over the next decade, LVMH used a stealth tactic common among hedge funds—cash-settled equity swaps—to secretly acquire 17 percent of Hermès, the 182-year-old maker of fine silk scarves and the iconic Birkin bag. Hermès fought Arnault off in a protracted battle that ended in 2017 with LVMH relinquishing most of its Hermès shares.

*****

Up close, Arnault’s polished appearance is like a suit of armour. On an overcast Friday morning in late September, he is attired in a selection of LVMH brands, including a pin-striped suit by Celine, a navy tie by Loro Piana, black leather slip-ons by Berluti and a white cuff-linked shirt by Dior with his initials embroidered just below his heart. Slim and 6 foot 1, he stays fit playing four hours of tennis a week, sometimes with his friend Roger Federer. “I try not to be fat, as you see, and I do a lot of sports,” he says.

Those games are among his only breaks from a workaholic schedule that starts at 6.30 am in his 17th-century mansion in the posh 7th Arrondissement on Paris’s Left Bank. He begins each morning listening to classical music, scanning industry news and texting family members and brand chiefs. “What I have in mind every morning is that the desirability of a brand should be as strong in 10 years,” he says. “It’s really the key to our success.” By 8 am he’s in his office at 22 Avenue Montaigne, where he stays as late as 9 pm. Occasionally he’ll take a 20-to-30-minute pause to play the Yamaha grand piano in a room down the hall from his ninth-floor office.

Four of Arnault’s five children work in corners of the LVMH empire. Clockwise from top left: Alexandre, Antoine, Frédéric and Delphine

Four of Arnault’s five children work in corners of the LVMH empire. Clockwise from top left: Alexandre, Antoine, Frédéric and DelphineImage: Clockwise from top left: Karl Lagerfeld, Mazen Saggar, Karl Lagerfeld, Jean-François Robert

“He works 24 hours,” says Delphine Arnault, 44, Arnault’s oldest child, from his first marriage, and the executive vice president of Louis Vuitton. “When he sleeps, he’s dreaming of new ideas.”

Every Saturday, he prowls his retail stores, rearranging bag displays and making suggestions to clerks. He visits as many as 25 stores, including the competition, in a single morning. “It’s a ritual,” says his son Frédéric, 25, who works at LVMH’s top watch brand, TAG Heuer. Arnault relays details from his store visits to the chiefs of his top brands. He recently alerted Louis Vuitton CEO Michael Burke that the new “it” bag, the $2,480 Onthego tote, was not in stock at the Place Vendôme shop. “He complains when too many SKUs are sold out,” says Burke, who has worked with Arnault since 1980.

At least once a month, Arnault travels in his Bombardier jet to visit some corner of his empire. In October, he visited the small town of Keene, Texas, where he and Donald Trump cut the ribbon on the first of two new Louis Vuitton workshops slated to create 1,000 jobs over the next five years. (The brand already has two workshops in California.) “I am not here to judge his types of policies. I have no political role,” said Arnault to reporters. Still, the event sparked a flash of controversy within his own ranks. Vuitton’s womenswear artistic director, Nicolas Ghesquière, wrote on Instagram: “I am a fashion designer refusing this association #trumpisajoke #homophobia.” Arnault didn’t respond to Ghesquière’s dig.

In late October, Arnault, Burke and Dior CEO Pietro Beccari were set to fly to Seoul to visit stores, including a new Frank Gehry-designed Vuitton outpost. It’s the sixth Vuitton store to include an art gallery that will show selections from the extensive collection of the LVMH-funded Fondation Louis Vuitton, which also rotates through the Fondation’s $135 million Paris museum (also designed by Gehry).

Even with the conglomerate’s massive footprint around the world—4,590 shops in 68 countries—store openings and closings often depend as much on Arnault’s gut and a neighbourhood’s ambience as on more traditional metrics like sales per square foot. In China, one of LVMH’s most important markets, he limits the number of Louis Vuitton shops to control the pace of expansion.

Last year, Louis Vuitton shuttered a store in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, because adjacent shops, restaurants and parking weren’t ritzy enough. Arnault visited a property on the Champs-Élysées multiple times before he approved a new Dior store near the Arc de Triomphe that opened in July, despite data showing the previous tenant had sluggish sales. “He pushes you to really be sure,” Dior chief Beccari says. “He wants to challenge you, that’s his tactic.”

*****

Showing up rivals is another tactic. In July, as apparel brands were competing to see who could be the most eco-conscious, he announced a partnership with the British fashion designer Stella McCartney (daughter of Paul), who has long touted her sustainability efforts (she says she even refuses to use glue in her sneaker line because it’s made from boiled animal parts). Arnault invited McCartney, who in 2018 ended a 17-year partnership with the Pinault family’s Kering luxury group (owner of Gucci), to become his “special advisor.” She accepted, despite LVMH’s decision to continue to make products with leather and fur (and glue). Arnault also declined to join the ‘Fashion Pact’, led by Kering and signed by 32 apparel makers, including Chanel, Hermès, fast-fashion giant H&M and even McCartney, who all pledged to lower carbon emissions.

Arnault then made his own series of eco-gestures during Fashion Week, when the media converged on Paris to cover the shows. At Tuesday’s Dior show, where models paraded across a stage decorated with 170 trees in dirt-filled burlap bags, the press was told that the theme was sustainability and that the electricity at the event was produced with generators powered by canola oil. The next evening, LVMH hosted 50 journalists for a two-and-a-half-hour event in an auditorium at company headquarters. Arnault and 10 LVMH brand chiefs took turns on a brightly lit stage reciting their commitments to environmental stewardship, their presentations interspersed with slickly produced videos of models strutting down catwalks and cashmere goats frolicking on the Mongolian steppes.

Mid-event, Arnault was asked to share his thoughts on young climate activists like 16-year-old Greta Thunberg. “I’m a natural optimist,” he said, “unlike Greta, who has a big problem, and that’s projecting an outrageous amount of pessimism in her messages without any real solutions.”

Not surprising for a corporate titan, he prefers not to dwell on problems. “He doesn’t like to hear the word ‘no’,” says Anna Wintour, the longtime Vogue editor. “It’s not part of his vocabulary.” Not from rivals, acquisition targets or even environmental champions.

McCartney is one of many big names he’s reeled in. In 2017, LVMH launched a cosmetics line, Fenty Beauty, with the pop star Rihanna, distributing the products through its retail beauty chain Sephora’s 2,600 stores. Capitalising on Fenty’s broad-audience offerings—its foundation comes in 40 skin shades—and on its founder’s 77 million Instagram followers, the division will hit $550 million in sales this year, Arnault says. He’s betting that Fenty Fashion, the apparel collection LVMH debuted with Rihanna in May, will meet with similar success. “She brings a different vision of fashion,” Arnault says. “For the future, it’s very good for us to be connected to millennials.”

*****

To keep his brands modern, he also looks to his five children from two marriages, four of whom work at LVMH: Delphine, 44; Antoine, 42; Alexandre, 27; and Frédéric, 25. His youngest child, Jean, 21, will likely join the company when he finishes school, according to Alexandre.

Shortly after he started as strategy and digital director at the Swiss watch brand TAG Heuer 13 months ago, Frédéric Arnault pitched an idea to his father over dinner. To enhance the brand’s smartwatch for golfers, he wanted to acquire a French startup, FunGolf, that had built an app with detailed terrain data on 39,000 courses. Players could use it to measure how far they were from sand traps or greens. “The people in the M&A department thought I was crazy,” he says. But once he made the case to his father, says Frédéric, “He said, ‘Go for it’.” Arnault regularly brings in big names. Stella McCartney (left) is Arnault’s new sustainability advisor, while LVMH launched a cosmetics line Fenty Beauty and later an apparel collection with pop singer Rihanna (right)

Image: Stella: Bertrand Rindoff Petroff/Getty Images; Rihanna: Peter Nicholls/Reuters

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)