The James Bond of Burgundy

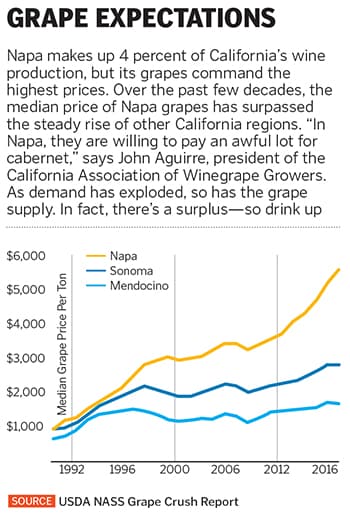

Winemaker Jean-Charles Boisset has stealthily built a $450 million oenological empire in France and California, one struggling vineyard at a time—and uncorked a lascivious secret-agent persona

Winemaker Jean-Charles Boisset at the Raymond Winery Dinner during the 2011 Napa Valley Film Festival in California

Winemaker Jean-Charles Boisset at the Raymond Winery Dinner during the 2011 Napa Valley Film Festival in California

Image: Randall Michelson / Wireimage / Getty Images

Jean-Charles Boisset quiets a long table of 50-plus guests in New York’s Meatpacking District as gold magnums of Champagne clink in the background. It’s a Last Supper–inspired meal for the French-born winemaker, part of his multi-city tour to promote a $395 coffee table book called The Alchemy of the Senses. As saumon à l’oseille arrives with a rich pinot noir, Boisset begins to explain his selection, an unusual blend of grapes from Burgundy and California called JCB No 3.

After inhaling deeply from a particularly wide crystal goblet that’s part of his new collaboration with Baccarat, Boisset admits that this dinner has caused him to miss the ten-year anniversary of his marriage to Gina Gallo, the third-generation face of the family behind the world’s largest wine producer by volume, E & J Gallo. During their engagement, they made a wine of the same origins together—blending, bottling and corking by hand—and then served it at their wedding as a symbol of her historic California roots becoming intertwined with his family’s own Burgundian heritage.

“Half of it is made in Burgundy, so that’s 49 percent of the blend,” Boisset says in a thick French accent before pausing dramatically. “I need to confess. I will tell you something very personal. My love likes to be on top. So 51 percent is California.”

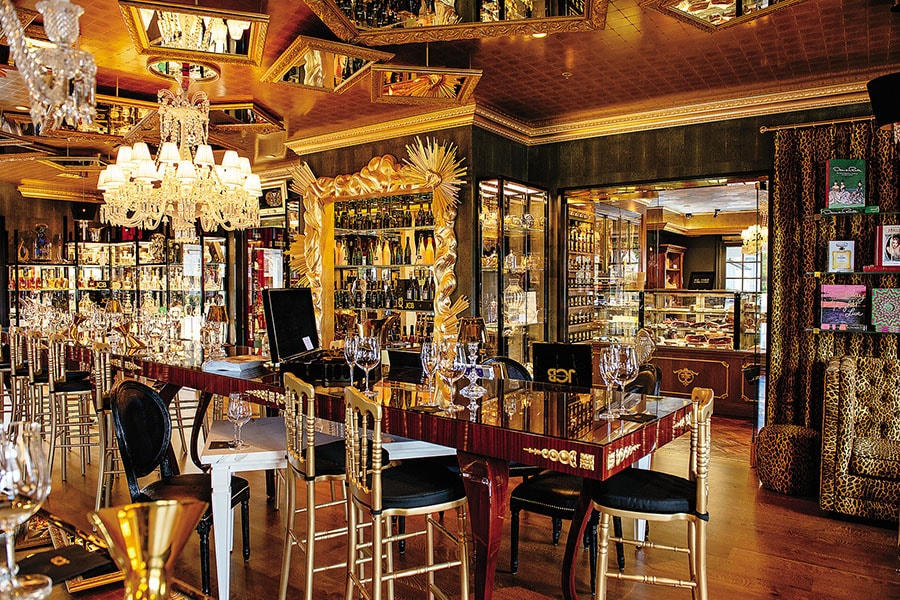

Sex is clearly the theme of this Boisset soirée, where the innuendo-filled jokes flow as freely as the wine. Leopard-print silk napkins sit on a red velvet tablecloth, and a mirror has replaced the ceiling (“Ladies, be careful, because I can see everything!”). Dates never sit together, and Boisset encourages touching (“You could still caress the person next to you. I see a lot of that is already happening, which I’m delighted to see!”).

The 50-year-old Boisset is blithely oblivious to the #MeToo era, and his guests seem to appreciate the single entendres. A few months earlier, Rob McMillan, founder of Silicon Valley Bank’s wine division, described Boisset as “the wine equivalent to Ringling Brothers—he’s an entertainer with flair and flash. He’s also a great businessperson‚ able to take a tarnished penny and shine it up”.

Along with his older sister, Nathalie, Boisset presides over close to 30 wineries worldwide, including a good portion of Burgundy’s vineyards. Annual sales are about $200 million; Forbes conservatively estimates the company to be worth some $450 million. If the collection were divided up at auction, many assets would likely sell for more than as part of the package. “Buyers are looking for a trophy purchase,” says Michael Baynes, executive partner at Vineyards-Bordeaux Christie’s International Real Estate. “There’s a lack of supply. The Boisset Collection would get a very premium price.”

The elegant tasting rooms at two of Boisset’s vineyards, Buena Vista

The elegant tasting rooms at two of Boisset’s vineyards, Buena VistaBack at Boisset’s Last Supper, he introduces JCB No 81, a chardonnay inspired by the moment in 1981 when he first became fixated on California wines. As the story goes, it was during a trip to Sonoma with his grandparents when he was 11 years old. After visiting Buena Vista winery, founded in 1857, Boisset turned to his sister and prophesied, “One day we will make wine together in California.”

Nearly a decade later, Boisset’s parents acquired a patchwork of properties throughout some of the most valuable parts of Burgundy through a combination of local bank loans and sheer luck. Because it was so hard to combine parcels, few others even tried.

The elegant tasting rooms at two of Boisset’s vineyards, Yountville

The elegant tasting rooms at two of Boisset’s vineyards, YountvilleHe brought that maverick philosophy to America. In 1991, Boisset started leading the family import business in San Francisco and searching for family-owned wineries with history to acquire. Buena Vista, after retreating from national distribution, looked promising, but the owners rebuked Boisset’s offer. “It was very innovative at the time, very iconoclast[ic] from a strategy standpoint. No one looked at California the way we looked at it,” he says.

He closed on DeLoach Vineyards in Sonoma instead in 2003. Boisset then began spending more time in California as DeLoach transitioned to biodynamic farming based on the lunar cycle. In 2007 he acquired the 300-acre estate of Raymond Vineyards in St Helena. Boisset finally secured Buena Vista in 2011, after trying at least four times.

After an acquisition, Boisset has three main strategies: First, every vineyard transitions to organic farming. Next, he increases the price of the wines, usually around 30 percent to 40 percent. (In the case of Raymond, the retail value of several bottles more than doubled to $45 each.) Finally, the wines are marketed with the rest of the collection to more than 600 partners worldwide. Buena Vista, DeLoach and Raymond, for example, are now sold in more than 20 countries each. Because Boisset’s wines range from $15 to $2,600, this system streamlines the buying process for distributors who can mix and match for different accounts.

“In Europe, if you come from Burgundy, you’re on the upper scale,” Boisset says. “But it’s too much stratification of society, perceived value and history based on heritage rather than who you are. In the US you could come from wherever, whoever, whatever. It’s about you. That’s what I really value. That’s what allowed me to become who I am.”

That includes his not-so-secret identity, Agent 69, an ersatz James Bond who brandishes swords and rescues women—and wine—at lavish parties and in several campy videos. It’s sometimes difficult to tell where the serious winemaker ends and the louche alter ego begins. At Raymond’s tasting room, visitors on tours are ushered past industrial tanks and mannequins hanging upside-down on fuzzy red swings, wearing sheer bras and leopard-print leggings.

Boisset has also commoditised his hyperactive libido. With Swarovski, JCB produces lines of jewellery, one of which, Confession, features handcuffs. There’s also a red wine called Restrained. The bottle is fastened with a leather bondage harness and O-ring.

Boisset’s business partners say they’re not put off. “He doesn’t hide who he is,” says Dina Opici, president of her family’s New Jersey–based wine-and-spirits distribution company, who has known Boisset for 15 years. “It is really genuine. He’s well-intentioned.”

With 10 wineries in the US and a growing private-label business, Boisset must now contend with an overcrowded wine market amid fast-growing categories such as hard seltzer and legalised cannabis. Last year, Americans’ wine consumption declined for the first time in 25 years, according to trade group IWSR.

But opportunities beyond wineries abound. Last year was particularly busy: Boisset acquired the nearly 140-year-old Oakville Grocery and founded Napa’s first wine-history museum. He also opened a strip mall called JCB Village in Yountville that features a tasting room, a day spa and a boutique that sells JCB label candles and dress socks along with Baccarat decanters inspired by Boisset’s own collection, which is the largest in the world. Amid declining Napa tourism, he has opened lounges outside the valley at the Ritz-Carlton in San Francisco, Ghirardelli Square’s Wattle Creek and the Rosewood Hotel in Palo Alto.

Boisset insists his luxury empire will continue to take years to build—and will withstand threats, be they wine tariffs, climate change or competitors. “You don’t build a luxury business in five minutes,” he says. “Besides LVMH and Pernod Ricard, two monsters, no one has had our journey. The American way of life drove me here.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)