Tomorrow's Ivy Leagues: Rethinking the business of education

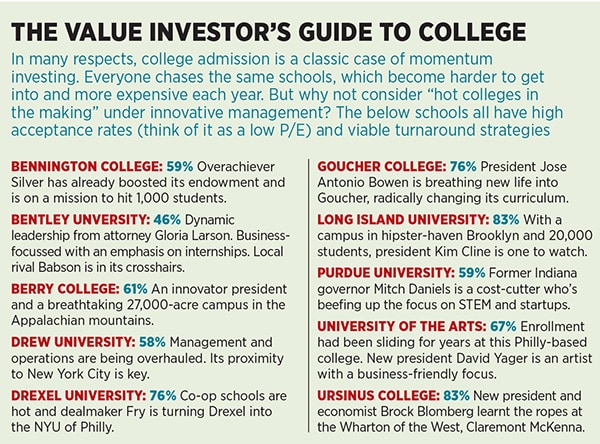

As hundreds of venerable institutions of higher education limp along, struggling to pay their bills, a new breed of innovative, activist college presidents are rethinking the business of education

Drew University always had an Ivy League look. Drive through the gated entrance of the leafy, 186-acre Madison, New Jersey, campus and you’re soon confronted by Mead Hall, a massive Greek-revival mansion built in 1836, with its brick façade, white portico columns and green colonial window shutters. The rooms inside are just as stately, with 20-foot-high ceilings and large oil paintings of the founders and past presidents staring down at you. But the mood starts to change as you walk across the grand foyer and up a long staircase to the president’s office suite.

Once there, you will meet MaryAnn Baenninger, the 13th president of Drew, and her cabinet of executive officers. Dressed in a tasteful pantsuit and silk scarf, Dr Baenninger may look like she belongs in an ivory tower, but hers is no stuffy academic administration. She and her team are change agents who have recently been recruited to turn around Drew, which had been haemorrhaging students and revenues.

It is one of hundreds of middling colleges around the nation that struggle each year to bring in enough students and tuition revenue to pay their bills. In 2015, the university, which has 2,151 students, accepted about 70 percent of applicants for its Class of 2019. (By comparison, schools such as Harvard and Stanford accept less than 5 percent.) But even with its generous acceptance policy, Drew is a perennial member of the “space available” list of colleges in need of freshmen well past the traditional May 1 deadline, because most of its accepted students prefer other schools.

And Drew’s discount rate—the percentage of tuition it rebates in the form of “aid” to attract students—recently hit an alarmingly high 69 percent. Despite that, freshman enrollment has fallen from a peak of 506 in 2009 to 302 in 2014, the year Baenninger arrived after righting the finances of the College of Saint Benedict in St Joseph, Minnesota.

Drew is in good company. According to the National Association of College Business Officers, the average institutional discount rate has been climbing for decades, to 49 percent for incoming freshmen, up from 39 percent in 2006. The epidemic of deep tuition discounting is a symptom of inefficient pricing policies, which disguise the poor fiscal health of most institutions. “There are more than 3,500 non-profit colleges, and most are struggling to get students,” says economist Lucie Lapovsky, a former college president who is now a consultant. “We have too many schools. They spend more and more on marketing and financial aid, and less is going into the investment in faculty and the direct delivery of education.” She adds, “A school of 1,000 students often has the same administrative structure as a school of 5,000.” Indeed, if ever there was an industry in dire need of bold entrepreneurial leadership, it is higher education, and Baenninger is the rare product of academia who actually gets it.

During the 1990s she was a psychology professor at The College of New Jersey. Back then it was called Trenton State College and was undergoing transformation from teachers college to full-blown liberal arts institution, now referred to as TCNJ. The College of New Jersey is now ranked number one in the Northeast among public colleges. From TCNJ, Baenninger became a director at the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, the accrediting organisation for some 526 colleges, where she got to examine the books and interview the administrations, faculty and students of about 100 schools, ranging from Princeton to Sarah Lawrence to Finger Lakes Community College. “It is a very rigorous process, covering finances, academics, facilities, student affairs and everything in between,” says the 60-year-old Baenninger. “It was an apprenticeship to be a college president.”

When she arrived at Drew, student retention, or the number of freshmen who continue on to sophomore year, had been bouncing between 75 percent and 85 percent, compared with about 98 percent for top liberal arts colleges like Amherst and Dartmouth. The all-important six-year graduation rate was a pitiful 62 percent, compared with about 95 percent at top schools.

“The reason we weren’t retaining kids didn’t have to do with the academics,” Baenninger explains. “It had to do with everything else. Just navigating the environment here was disproportionately complicated, and there was an annoying bureaucracy that didn’t fit with a caring liberal arts institution.”

Baenninger is referring to what undergraduates call the “Drew screw”. Simple tasks like switching a class or handling a financial aid problem or fixing a dorm room issue became bogged down in red tape. Part of the problem is endemic to higher education, which is notoriously inefficient. However, some of Drew’s problems were the legacy of previous administrations, including the 15-year presidency, until 2005, of former New Jersey governor Thomas Kean, who concurrently served as chairman of the 9/11 Commission and added on layers of bureaucracy befitting his status.

Baenninger moved quickly to streamline and overhaul management. “The number of new employees here is staggering,” she says of the new Drew. “The only way you can change the culture is to change key people.”

Among her first hires was Robert Massa as vice president of enrollment. Massa is renowned among higher education insiders for helping to rescue Johns Hopkins during a budget crisis at its school of arts and sciences in 1989. After a decade instilling enrollment discipline at Hopkins, Massa reversed a severe enrollment decline at Pennsylvania’s Dickinson College, in part by championing its then-radical SAT-optional strategy. During his ten-year tenure, Dickinson’s admissions rate fell from about 60 percent to 40 percent, and the liberal arts college rose in the rankings.

Another key hire was Kira Poplowski as vice president of communications and marketing. Poplowski cut her teeth at Pitzer College, once regarded as the red-headed stepchild of the prestigious five-college Claremont, California, consortium. At Pitzer, Poplowski was part of the team that rebranded the school’s image from an easy-A college for leftist stoners to one steeped in academic excellence and sustainable, green living. Pitzer’s admit rate has plummeted from about 50 percent in 2003 to 12 percent in 2016.

Baenninger also sought talent outside of academia. Marti Winer, Drew’s chief of staff, spent seven years in hospitality management for Wyndham Hotel Group and was also an active member of the college’s alumni board. “Marti knows Drew, but she also has the corporate background and doesn’t suffer fools gladly,” says Baenninger, who has made a practice of temporarily installing Winer in key administrative roles after she fires staffers.

“We are building a culture of accountability in an environment where shirking responsibility has been easy,” says Winer. “This was a huge paradigm shift for us.”

To make sure she wasn’t perceived as an all-stick-and-no-carrot manager, Baenninger began doling out bonuses, but only to those who exhibited leadership that went above and beyond their specific job description.

“The second important value we are instilling is customer service,” says Winer, noting that the term “customer” makes most in academia bristle. “At every touch point you have, it has to be a good experience.”

Baenninger recalls one incident early in her tenure, when the former registrar refused to accommodate a transgender alumna who wanted to have the name on her diploma changed to reflect her new identity. As soon as Baenninger got wind of the unhappy alum, she reversed the registrar’s decision. “‘We can’t change history’ was the former registrar’s excuse,” scoffs enrollment chief Massa.

To attract the right student applicants, Massa and Poplowski have focussed Drew’s marketing on three concepts under a “Declare Yourself” theme: Proximity to New York City (Drew is a 45-minute train ride from Penn Station), experiential learning and mentorship. And to help new students navigate the city, all freshman seminar teachers are required to escort their classes on a full-day course-related Manhattan field trip. Drew’s “Find Your Yoda” marketing slogan reinforces the school’s Ivy-level student-to-faculty ratio of 10 to 1.

To get the word out, Baenninger got permission to dip into Drew’s $214 million endowment and increased budgets to allow Poplowski and Massa to execute their vision.

Poplowski hired the New York design firm Pentagram to revamp Drew’s marketing assets. Drew’s new branding shows an oak leaf featuring a silhouette of the Manhattan skyline in its centre. Massa hired new admissions officers, including a veteran with deep connections at elite private high schools.

Less than two years into its turnaround, Baenninger and her team are making excellent progress. Applications increased for the first time in six years—by 15 percent—in 2016, and enrollment jumped by 20 percent, to 360 for the Class of 2020. Early-decision enrollment doubled, and transfer students increased by 28 percent. Drew’s average SAT scores went up by 30 points, and its admission rate fell from 70 percent to 58 percent. Retention to sophomore year has climbed to 88 percent, Drew’s discount rate fell by eight percentage points, and net revenue per student increased by about $5,000.

The transformation is far from complete, but given the university’s operational reboot and its location, it’s easy to see how Drew (ranked No 274 on Forbes’s top colleges list) might one day join other elite schools once considered “safeties” and are now highly selective and financially secure—schools like New York University, Northeastern, Pitzer, Tufts and the University of Southern California.

Just back from a vacation at his beach house in Amagansett, New York, Drexel University president John A Fry is driving his son’s Toyota FJ Cruiser through the streets of West Philadelphia, pointing out all the buildings he has either rehabilitated or constructed in the past few decades. “There’s the Inn at Penn and the Penn Alexander School,” he says, referring to the University of Pennsylvania’s luxury hotel and Philly’s award-winning K–8 public school.

A few minutes later we are on John F Kennedy Boulevard, close to Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, passing a large parking lot, some unsightly industrial buildings and a Firestone auto repair. “This is a property I purchased in 2011 for $21.8 million,” says the 56-year-old Fry—part of a growing number of university presidents without a doctorate.

An MBA who spent the beginning of his career at Peat, Marwick and Coopers & Lybrand consulting with universities and other non-profits, Fry was hired by the University of Pennsylvania’s then-incoming president, Judith Rodin, in 1995, after a strategic plan he developed convinced her that he should be her new executive vice president, effectively putting him in charge of all of Penn’s non-academic affairs. “I had to go from a 25-person boutique consulting practice to administrative COO of this organisation with a $3 billion budget and 27,000 employees,” says Fry, who was 34 at the time.

Using Penn’s ample capital to partner with local developers, Fry was the driving force in rehabilitating the once crime-ridden University City area, now one of the most desirable parts of Philadelphia, with an array of fancy restaurants and retailers. “We have people who bought homes there for $100,000 and $200,000 that are now worth $800,000,” says Fry.

In 2002, Fry took his neighbourhood revitalisation and public/private partnership strategy to his next stint as president of Franklin & Marshall (F&M) College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. At F&M, Fry sought to drastically alter Lancaster’s landscape by moving a rail yard a mile down the road, demolishing an abandoned linoleum factory and rehabilitating a landfill, which had cut off the campus from the city and caused its students to be constant crime victims. The move would effectively double the size of the campus and pave the way for another vibrant retail and residential renaissance.

In 2010, before Fry could fully realise his Lancaster remake (during his tenure, F&M’s admission rate fell from 62 percent to 45 percent; it is now 32 percent), he was tapped to return to Philadelphia, after the longtime and beloved president of Drexel, Constantine Papadakis, died of lung cancer at the age of 63.

Today Fry wears a popular Lokai bracelet, with its black bead containing mud from the Dead Sea, peeking out from his tailored suit cuff. The bead symbolises hopefulness for those at a low point in life. And from an admissions standpoint Drexel is at rock bottom. It currently accepts nearly 80 percent of its applicants, yet its yield has been a pitiful 8 percent, meaning that only one in 12 accepted students actually chooses Drexel over rival schools.

Fry expects Drexel to shed its long-standing reputation as an easy-admission commuter college with a sprawling hodgepodge of a campus. To shore up admissions, he brought in Randall Deike as the school’s senior vice president of enrollment and student success. In a similar position at NYU for five years, Deike played a big role in the school’s ascendance in selectivity and other college rankings.

While Deike refocuses the university’s admissions strategy—Drexel recently terminated its free “fast app” programme, which brought in more than 47,000 applicants in 2014, many of whom knew little about the school and had no intention of attending—and pushes Drexel’s cooperative, experiential learning, and its emphasis on science and engineering, Fry is executing a grand plan to redevelop the blighted neighbourhoods adjacent to Drexel, which abuts the Penn campus. However, unlike Penn, which has a $10 billion endowment, Drexel, with a modest $670 million endowment, lacks deep pockets.

So Fry has teamed up with two Reits, Brandywine Realty Trust and American Campus Communities, to develop large tracts of land around the Drexel campus. Drexel’s neighbourhood remake will include some $5 billion worth of real estate development, including a $3.5 billion “Innovation Neighbourhood” along the Schuylkill River rail yards, which will include research facilities and an incubator space, a $58 million hotel called The Study at University City, a child-care centre, a public high school and some $340 million to be spent on three high-rise student apartment complexes and a dining centre.

In another move, Fry recently acquired Philadelphia’s struggling 204-year-old Academy of Natural Sciences. “It was totally asset-rich: A $50 million endowment, 18 million objects, a coveted piece of real estate, but no liquidity,” says Fry, who used a $1 million grant from the Pew Charitable Trust to finance it. Now Drexel offers majors in a new Department of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science, and the academy’s acclaimed research scientists have improved Drexel’s student-to-faculty ratio. “We won’t outspend anyone to victory,” says Fry, noting that Drexel will own all the land under the buildings, “but we can out-hustle and out-partner any other institution.”

With a few notable exceptions like Bowdoin and Middlebury, small rural campuses in frigid northern locations are generally a tougher sell to prospective freshmen. So when the board of trustees of Bennington College in Vermont were looking for a president with fresh ideas, they chose 35-year-old Mariko Silver, whose non-linear path to the top of academia epitomises the type of unconventional education Bennington has long offered.

When she got the call from the headhunter charged with Bennington’s search in early 2013, Silver was three months pregnant and planning a move to Hanoi, working on a project for Arizona State University, USAID, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and Intel to rethink engineering education in Vietnam.

Among academics, Silver is a wunderkind. A descendant of Jewish and Japanese immigrants, whose father was an award-winning documentary filmmaker and whose mother was chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, Silver had a first-rate education. In high school she attended New York City’s Fieldston and Los Angeles’s Harvard-Westlake, then went on to Yale. Silver turned down Oxford to pursue a master’s degree in science and technology policy from the University of Sussex in England, and was then considering business school.

But in the summer of 2001, a serendipitous cocktail party conversation connected Silver, then 23, to Michael Crow, the vice provost of Columbia University, who recruited her to be his tech policy specialist, essentially bringing together academic research and industry to get products to market. The endeavour had already produced more than $1 billion in royalties for Columbia. Following 9/11, Columbia was chosen to lead a multi-institutional research response to terrorism. Silver, already becoming known as a gifted, get-the-job-done project manager, organised the programme.

Then in 2002, when Crow became president of Arizona State University, Silver went with him as director of strategic projects and played a key role in ASU’s transformation, from a sports-crazy party school with bloated academic departments to a more efficient, leading research university with new public-private partnerships in fields like genomics research. During her initial six years at ASU, Silver earned a doctorate in economic geography from UCLA, but then in 2008, Arizona governor Janet Napolitano asked Silver to be her policy advisor on economic development, innovation and higher education. Six months into that job, US President Barack Obama picked Napolitano to be Secretary of Homeland Security, and Silver went along as an undersecretary and international strategist. After nearly three years Silver returned to ASU as special counsel to Crow and a professor in the department of politics and global studies.

Silver’s new challenge is to revive Bennington’s tired brand among artsy small colleges. When she arrived in 2013, applications were falling and enrollment had dropped to just 159 freshmen, despite an acceptance rate of 65 percent. Retention was only 83 percent. Bennington’s puny $17 million endowment didn’t offer Silver much of a cushion, considering the tiny Vermont school competes for students with better-endowed colleges like Bard, Sarah Lawrence and Skidmore.

“Bennington is an undervalued asset,” insists Silver, now 38. “That means it has something major to contribute to society.” Silver points out that each of its 675 or so undergrads is tasked with creating his or her own “learning plan” and must arrange for a seven-week off-campus field study each January and February. “Unlike other schools, Bennington forces students to learn how to be strategic. You have to build your strategy brain to move through a Bennington education,” she says, mentioning that one of the Class of 2016 graduated with a concentration in space architecture.

One key hire for Silver has been CFO Brian Murphy, an accountant and one of the architects of the Savannah College of Art & Design’s rise to prominence among art schools, with its 12,000 students and its campuses in Atlanta, China and France. Another is the vice president and dean of admissions and financial aid, Hung Bui, a former admissions officer at Colby College who earned an MBA from Carnegie Mellon and spent nine years as an analyst and fund manager.

Almost immediately, Murphy implemented a new accounting system and dismissed KPMG, Bennington’s accountant. “I used to be a senior tax manager at KPMG. A tiny school doesn’t need to be paying Big Four rates,” says Murphy, who also dismissed Bennington’s endowment manager because of poor returns.

Working with data-driven Bui, who devised his own spreadsheet-based model to shape Bennington’s freshman class, Murphy is tackling the biggest Achilles’ heel for tuition-dependent colleges: The discount rate, which was hovering around 58 percent.

Says Murphy, “For the more affluent family, aid may be immaterial. It may even be counterproductive. You may come across as desperate as an institution.”

According to Bui, Bennington still suffers from a reputation among guidance counsellors of being a place for rich kids, which, believe it or not, is a legacy of mentions on 1980s sitcoms like Cheers (Diane went to Bennington) and The Cosby Show (Theo wanted to go). Today Bui is smarter about doling out dollars.

Bennington has widened its net for new applicants, as Bui and his team have increased high school visits by 33 percent and introduced a new “dimensional application,” which allows high school students to have complete control of their own application, using any medium or format, in lieu of transcripts and standardised test scores. “Before I came, Bennington was looking for that one student at each high school,” says Bui, referring to the college’s elitist philosophy that Bennington students were unique. “In reality, there are many students that would be attracted to this type of education. There is a hunger for this type of education in China and internationally, where the educational path is more rigid.”

In the fiscal year ending June 2015, Bennington had a $2.2 million operating surplus, up from a deficit of $6.9 million the year before. The college’s discount rate has fallen to 43 percent. Applications jumped by 14 percent this year, and enrollment has climbed to 203 freshmen for the Class of 2020. Bennington’s acceptance rate fell below 60 percent for the first time in more than 20 years. About 13 percent of Bennington’s students are international, but those lucrative prospects should increase.

Bui is organising a tour of China in September, including a symposium at Beijing’s luxurious Peninsula Hotel on ‘The Importance of Innovation and Creativity in Higher Education’. The hotel is offering the venue free of charge, and Stanford and Johns Hopkins—both coveted and far more selective than Bennington—have agreed to join the agenda, so it is likely to be packed with Chinese students and parents. Of course, Bennington president Silver will be delivering the keynote address.

The new Bennington means business, and it’s not the Chinese who need to hear her lesson.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)