Utah: Cloud's new capital

Led by three unicorns eyeing an IPO, Utah is becoming as well-known for its cloud as for its mountains

Ryan Smith, CEO and co-founder of analytics firm Qualtrics, is helping make the Beehive State cloud nine for tech startups

Image: Tim Pannell for Forbes

In a particularly decadent McMansion, complete with personal theatre, tennis court and replica hobbit hole, in the appropriately named Alpine, Utah, a few miles north of Provo, the clock ticks past 1 am. Wide awake on a couch, Josh James, founder of the $2.3-billion business-analytics software company Domo, sits in the enormous kitchen, flanked by two of his unicorn rivals: Ryan Smith, co-founder of Qualtrics, and Aaron Skonnard, founder of Pluralsight. At least once a quarter, the trio puts down their swords and meets for an all-night jam session designed to forge consensus out of the earshot of their employees and without missing weekend time with their combined 16 kids. This one is fuelled by chocolate chip cookies and Monster energy drinks, caffeine-fuelled bombs you wouldn’t expect of three coffee-shunning Mormons. Then again, the topic at hand is how to attract more diversity to Utah—around Provo, Mormons make up 97 percent of the population—America’s eighth-whitest state and the third worst when it comes to gender pay disparity.

“I’m sick of words and statements on this,” Smith says as the others nod. “Let’s settle on three or four things we agree on that we can actually do at our companies.” The head of a local non-profit organisation for entrepreneurs takes notes as his three board members speak. Gary Herbert, Utah’s governor, stopped by earlier, pledging infrastructure improvements and student work programmes that can add to the talent pool. And now the group is reviewing the roster of speakers at a tech summit they’re backing at the Salt Palace in Salt Lake City, an event coinciding with the more famous Sundance Film Festival, trying to make sure more VIPs don’t look like them. Smith tells the others how Qualtrics ripped up its maternity-leave policy and started over with female employees in charge of it. Skonnard proposes that local tech companies release joint diversity reports. James wants to impose mandatory interviews for diversity hires in certain roles, in a startup version of the NFL’s Rooney Rule.

At 2.15 am, the group releases their scribe, Clint Betts, and Skonnard departs for the hour drive north to Farmington, where Pluralsight is based. Smith and James linger to speak privately until after 6 o’clock. “I don’t think our own employees know how much we talk,” Skonnard says. “They’ll interview for jobs and think we won’t tell each other.”

Silicon Valley, of course, is famous for its cut-throat culture, with the real estate bidding wars and the talent scrambles to match. From Boston to Austin, Seattle to Santa Monica, North Carolina’s Research Triangle to New York City’s Silicon Alley and other places in between, American regions have long aspired to build an alternative tech capital.

Now Utah is making its play. The state has a legacy of modest tech success: Novell and WordPerfect rose here in the 1980s; Overstock.com pulled off an IPO in 2002; and Ancestry.com dominates online genealogy. Adobe bought James’s first company, Omniture, for $1.8 billion in 2009. If Silicon Valley knows how to make great engineers, Utah breeds salespeople. Hawking security systems or enterprise software isn’t so hard when you’ve spent two years on a mission trying to convert strangers to a new religion, which is why—in addition to aggressive state tax breaks—tech giants like Microsoft and Oracle locate sales offices and call centres in Utah.

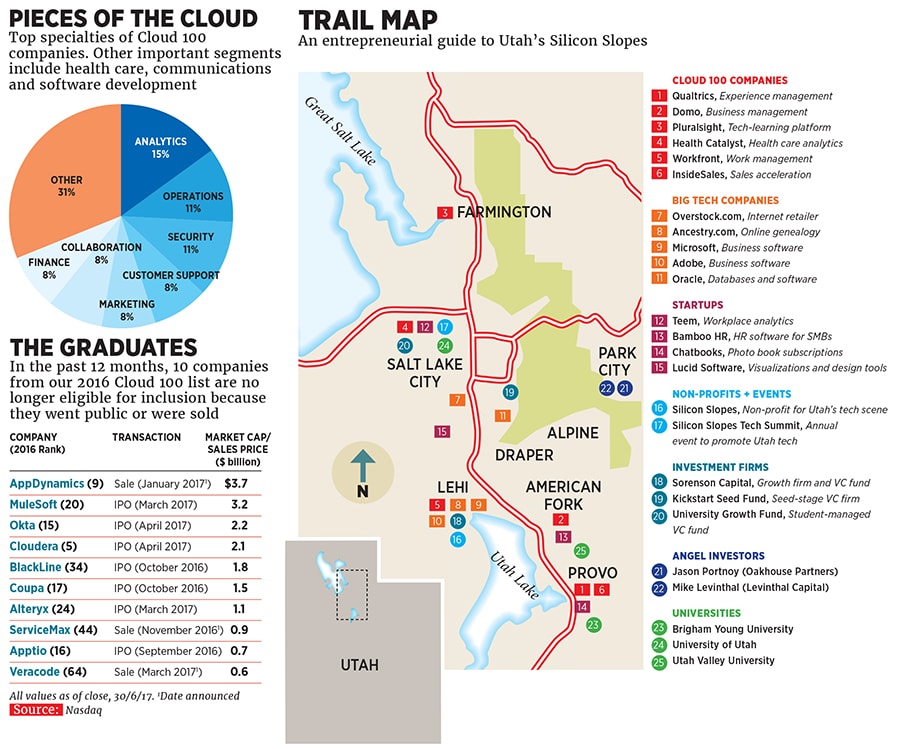

But that was before the advent of the cloud. That sales prowess, mixed with business-friendly policies, an educated workforce, low energy prices and a culture of deliberate growth, dovetails with a new tech era that requires huge server capacity and even larger contracts. The Beehive State hosts six companies—led by Qualtrics (No 6), Domo (15) and Pluralsight (20)—on the Forbes Cloud 100, a list of the leading private tech companies in cloud computing, which today spans everything from infrastructure to business software to cybersecurity. Dozens of cloud-focussed startups are incubating behind them. “We all have a chance to do something great,” Smith says. “We know the enormity of what we are doing.”

Image: Tim Pannell for Forbes

For decades, Utah County and its tech cluster in Provo was known (sometimes with irony) as “the Happy Valley”. More than ten years ago, James opportunistically trademarked a new catchphrase, dubbing the 60-mile stretch from Farmington down to Provo “Silicon Slopes”. After years of precocious marketing, Silicon Slopes is now for real.

In basketball-crazed Utah, Smith has a court in his basement, and he takes it farther at work: A hardwood half-court right inside the front door at Qualtrics’s new headquarters, where he shoots three-pointers with executives and random junior staff to alleviate stress. The company provides software that measures customer satisfaction and employee engagement for clients. More than 100 people started at Qualtrics in late June, swelling its numbers to almost 800 at the headquarters and 1,500 worldwide, and sales growth has it on pace to do $250 million in revenue in 2017, up by about 50 percent from last year. But Qualtrics is far from an overnight success. Smith started it 15 years ago. Pluralsight and InsideSales (No 92 on the Cloud 100) are both 13 years old; Workfront (58) is 16, and Health Catalyst (64) is approaching a decade. Even Domo, as James’s second company and the one built the most on Silicon Valley tactics, is 7—the average age of a startup exit.

Slow and steady growth, with a focus on profits over nascent market share, may seem old-fashioned, but with flameouts proliferating in Silicon Valley, that Utah bootstrapping culture has been attracting investments from the likes of Benchmark, Insight Venture Partners and Sequoia Capital—albeit usually after the companies are profitable and thus can negotiate with the venture capitalists (VCs) from strength.

That’s how Qualtrics did it. Smith dropped out of BYU to work on it out of a basement with his father (a former professor at the university), his brother Jared and a college roommate, Stuart Orgill. The idea: Put surveys and questionnaires on the internet, allowing anyone to conduct market research. Qualtrics raised its first outside capital only in 2012: $70 million for a company used in universities across the world and that had already been profitable for a decade.

Pluralsight first got started in software as a way for Skonnard to put online the corporate training classes that had been dragging him to Europe on dozens of round-trip flights for three years. Profitable since its four co-founders each put in $5,000 to get under way in 2004, the company shifted gears again in 2010 to focus on providing its technical proficiency training to corporations. Pluralsight went nine years before raising outside capital: $27.5 million from Insight and then $135 million from Iconiq Capital, Utah-based Sorenson Capital and others so it could make eight startup acquisitions and absorb their offices.

James didn’t take venture capital for years at Omniture. When the company went public, it was still something of an oddity to Wall Street—less so when Adobe acquired it for $1.8 billion three years later in 2009. With his second go, for Domo, James raised money the Silicon Valley way: $690 million in seven years for a company that connects all of a customer’s sources of data, up to 300 billion rows per client, to track the health of the business in real time. But that conservative business culture remains. While James drives sports cars and jets to Idaho for summer weekends, employees must remain austere. “Just because I’ve made it before, doesn’t mean we have at Domo,” James says on the way to shoot skeet with his contractor on a Saturday afternoon. “Utah’s culture generates extremely ambitious entrepreneurs who tend to be quite frugal,” says Bryan Schreier, a partner at Sequoia Capital who led its investment in Qualtrics. “I think there are more great companies per capita in Utah than anywhere else.”

With 100,000 students in the Provo area, many paying just $4,000 a semester in tuition, prospective employees emerge from universities debt-free and sales-driven. At BYU, 65 percent of students go on a mission as part of their Mormon faith, many of whom learn a second language. Research by BYU Marriott School professor Jeff Dyer, MIT’s Hal Gregersen and Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen has found that people who live six months abroad are twice as likely to start a new product or company. At Qualtrics, where Jared Smith helped instil Google-style hiring processes and interview questions upon his return from a six-year stint, completion of a Mormon mission counts as “sales adversity training”, which boosts a candidate’s résumé—bonus points if the candidate went “somewhere hard”. Until it raised $70 million from Sequoia and Accel Partners in 2012, Qualtrics was light on engineers but heavy on young salespeople willing to work relatively cheap. “That’s how you make 100,000 cold calls in a quarter and don’t get fazed,” Jared says.

Collaboration helps. You won’t find turf wars or ego-driven battles among Utah cloud companies. In June, Domo sent a delegation to Health Catalyst for four hours, and that’s quite typical. Each niche within the same field is respected by the others. While James is rare in sitting on InsideSales’s board of directors, the whole group maintains endless text threads and even vacation together. “I’m a businessman, but we trust each other,” says Skonnard at Pluralsight. “There’s a shared vision for Utah that unifies us.”

Utah’s cloud-based surge remains contingent on one thing: More outside talent. Which is why, ostensibly, Smith and James find themselves at Oakland’s Oracle Arena, at the clinching Game 5 of the NBA Finals. Yes, they love hoops. But they love recruiting more, especially from the Bay Area, including shelling out $10,000 per seat for the hottest ticket of the year in a region smitten with the Golden State Warriors. After spending the day interviewing candidates in San Francisco, Smith works the crowd, all the way down to courtside, like a seasoned politician.

James is here to treat his new chief marketing officer and to woo the business-operations executive at a direct competitor he’s spent weeks trying to recruit. “We’ve talked on the phone a few times, but this is the first time we’re meeting face-to-face,” says the veteran software executive. It’s certainly a memorable one: The executive got to be a hero by bringing his son as well, and they sat one row behind LeBron James and the Cavaliers’s bench. “It’s an offer you can’t refuse.”

Like the companies themselves, the pitch often comes down to lower costs: A flat 5 percent state tax and a cost of living in Provo that’s 30 percent less than Seattle’s and 41 percent less than Boston’s—and half that of the Bay Area, despite the fact that salaries are only 27 percent smaller, on average. The Utah cloud companies have opportunistically brought back BYU graduates who had left the state, such as new Qualtrics chief operating officer Zig Serafin, who had spent 17 years at Microsoft as head of what became Skype for Business and as president of its TellMe unit, and Pluralsight’s new CFO, James Budge, who plans to move his family from California next year.

And these companies have shown the flexibility to attract others from out of state, as Qualtrics alone has relocated 160 people to Utah so far this year. Want upside? Pluralsight’s Skonnard got Budge, the CFO of Anaplan, to jump by paying him entirely in stock (and $1 in salary). Internal chatter at Amazon Web Services (AWS) about their hottest customers helped Domo hire its chief strategy officer, who became intrigued by the startup’s prospects after noticing it spending more and more with AWS.

And Utah has developed an efficient commuter rail system that connects Provo to more cosmopolitan areas of the state. As recently as a year ago, Qualtrics operated one shuttle from its campus to the train station; the company has increased that to five as young relocated employees like Jesus Perez, an account executive and Penn graduate, opt to live in high-rises in Salt Lake City—which has a gay mayor and reportedly non-Mormon majority. Heather Zynczak, Pluralsight’s CMO, says she loves the size of her house in Park City, the ski resort town where non-Mormon tech executives bump into each other getting coffee or dropping their kids off at the lifts. Milind Kopikare, a Qualtrics product manager, chose Draper, a suburban town with a burgeoning Indian-American population. “There’s a big Indian temple there,” he says. His neighbours work in nearby tech centres for American Express and Goldman Sachs.

Expanding offices in Europe, Seattle and cities such as Chicago allow the Utah companies to hire executives who work remotely or commute. Pluralsight’s head of sales lives in New York. Domo’s CFO and chief strategist and several other senior hires commute to headquarters two or three days a week from out of state. And InsideSales’s chief revenue officer, Lindsey Armstrong, helps keep the company moving from London. “I travel all the time, but not necessarily to Provo,” Armstrong says. “I like to maintain that at almost any given time, someone is pissed off at me for being in the wrong location.”

The collaboration between Utah’s cloud founders extends past their regular all-nighters. When Goldman Sachs recently hosted Smith at a golf outing at the famed Shinnecock Hills course in the Hamptons with other tech executives, he noted how rare it was that he would do something like that without Skonnard, James or both. “The banks will ask for the ‘Utah guys’,” Smith says, “because they know then we’re more likely to go.”

The “Utah guys” are all likely to go public soon, though “soon” is a relative word for companies whose life spans far exceed the typical startup story. Smith says he left money on the table when Qualtrics reached a $2.7 billion valuation in April (it was widely reported as $2.5 billion, which suited him just fine). Easy enough: With roughly 20 percent of the company, Smith is worth more than $500 million. Qualtrics’s current focus is to build on top of its survey tools, helping businesses track the happiness of customers and employees through a range of channels it hangs under the umbrella term “experience management”. Pluralsight’s Skonnard says he could be the closest to an IPO. Skonnard owns roughly 20 percent of the company, a stake likely worth $200 million, while controlling the voting rights for 60 percent. A month ago, he loosened his grip somewhat, sharing equity with employees for the first time, based on their length of service. A new focus on enterprise customers in the past year has put Pluralsight inside 40 percent of the nation’s 500 biggest companies, some of which now pay for thousands of seats, while the head count has doubled in two years to 640. “We’re moving quickly in this phase,” he says.

Domo’s valuation stayed roughly flat at $2.3 billion during its last funding from BlackRock in April, as the market got tougher, its CFO says. While that would make James’s stake worth around $575 million, he says he’ll start looking closer at the public markets a year from now. The company may require significant additional funds to reposition itself as an operational tool that will allow its customers to make purchases and staffing decisions within the app. Domo leadership is seeking to distance itself from the nifty visualisations and charts that are the mainstay of troubled competitor Tableau.

It’s another story at InsideSales, which moved in the wrong direction on this year’s Cloud 100 list. In a steampunk-influenced office of wood beams and wrought metal doors in Provo, CEO David Elkington sits in the dark near rows of empty desks. He recently hit the brakes on customer growth to focus on keeping the ones he already had, adding new predictive features to his sales-acceleration software. He says his billion-dollar-plus valuation (reported as $1.5 billion) was a distraction. “I started down that path of raising and hiring, and eventually I said I don’t enjoy this,” says Elkington, who has turned over much of his management team. “So I had to say, ‘Screw them, I’ll do it my way again’.”

When Utah’s cloud companies go public or get acquired, each founder says he’ll be cheering his peers on, even if that means breaking up the Utah guys’ collaboration. The adversity they faced is a thing of the past. Between Silicon Valley venture firms hunting in Utah and ascendant local shops like Sorenson Capital, which just launched its first venture capital fund, access to cash is much easier now, and talent will continue to trickle in, regardless of outcome. A recent barbecue for local tech workers in Lehi, halfway between Provo and Salt Lake City, drew 5,000 people. The challenge will be to retain Utah’s magic at scale. “I feel bad for companies that didn’t have to go through what we did,” Smith adds. “When Josh sits on a board, it’s all about the scar tissue he can pass on.”

And just as the boom in Silicon Valley eventually became a boom 45 minutes north in San Francisco, so is Silicon Slopes creating a startup scene in Salt Lake City, including the 80 employees of Teem, which offers cloud-based software that manages conference rooms. Airbnb was a key early adopter, though other Silicon Valley startups resisted a bit when they found out they were buying Utah tech. “So we just put a 415 number on our website,” says CEO Shaun Ritchie, invoking the area code for San Francisco. “The question never came up again.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)