Vivek Ramaswamy: Boy in the bubble

As the biotech market boils over, prodigy Vivek Ramaswamy is engineering a flurry of deals that rescue drugs forgotten by the big firms. It might make him a billionaire at 30

In June, Vivek Ramaswamy, a 29-year-old former hedge fund partner, cancelled his honeymoon plans to hike in the French and Swiss Alps. He instead brought his bride to stand beside him as he rang the bell of the New York Stock Exchange to launch the biggest initial public offering in the history of the American biotechnology industry.

What could be more romantic than a few hundred million in paper gains in a single day?

Ramaswamy’s Bermuda-based company, Axovant Sciences, had been formed only eight months earlier, but here it was raising $360 million to develop an Alzheimer’s drug that had been all but abandoned by giant pharma GlaxoSmithKline. On the first day of trading, the stock almost doubled, giving Axovant a market capitalisation of nearly $3 billion. Considering that Ramaswamy had persuaded Glaxo to part with the unproven remedy for just $5 million upfront, the newlyweds were ecstatic, as was a veritable wedding party of hedge fund pals who had followed Ramaswamy into the stock.

Yet as quickly as it started, the honeymoon was over. ‘Why would Glaxo sell off a promising drug for so little?’ critics asked. And how could a company with ten employees, two of whom were Ramaswamy’s mother and brother, be worth so much? Experts, analysts and the collective blogosphere quickly piled on, and Axovant’s shares went into free fall. By early September, they were trading 12 percent below the IPO price.

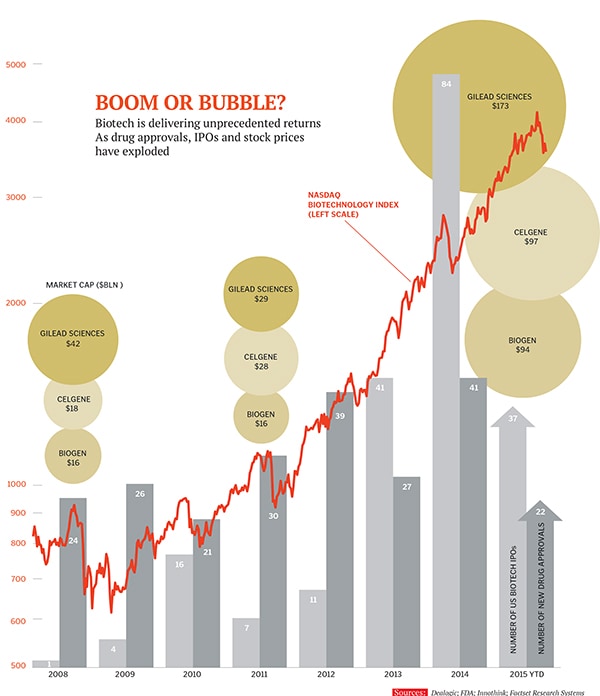

The naysayers have positioned the young and charming Ramaswamy as the poster boy for a biotech bubble. That’s not hard to do when the iShares Nasdaq Biotechnology Index has surged 300 percent in five years, compared with a 100 percent gain for the broader Nasdaq index and 70 percent for the S&P 500. Scary numbers, despite a plethora of real breakthroughs, including cancer drugs that shrink tumours, cures for hepatitis C and treatments that replace defective genes. And they’d be positively terrifying if the government stops approving or paying high prices for so many drugs.

But this creeping fear ignores the full scope of what Ramaswamy is up to: Rescuing the pharmaceutical industry’s forgotten drugs. Whether or not the Axovant drug works, the IPO, according to Ramaswamy, is “a first step on a broader mission” to liberate abandoned or deprioritised drugs that routinely languish in the pipelines of pharma companies. “It’s an ethical problem of an underappre- ciated magnitude,” says Ramaswamy. “So many drugs that would have been of use to society are cast aside. Certain drugs have gone by the wayside for reasons that have nothing to do with their underlying merits.”

Leaning on his Wall Street back- ground and armed with a $400 million war chest, Ramaswamy is building a portfolio not of stocks but of has-been drugs that he grabs for “pennies on the dollar”, free-riding on the billions in research that pharma sometimes sinks into failed trials. Using a pharmaceutical holding company he formed last year, Roivant Sciences, Ramaswamy hopes to spin out dozens of companies, much as he did with Axovant. “This will be the highest return on investment endeavour ever taken up in the pharmaceutical industry,” he boasts. “It will be a pipeline every bit as deep and diverse as the most promising pharma company in the world but with a capital efficiency that is unprecedented.”

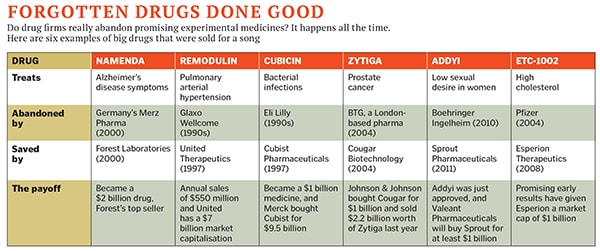

There’s precedent. Lipitor, the best-selling drug ever, was almost abandoned, and Imbruvica, the drug behind AbbVie’s $21 billion purchase of Pharmacyclics in May, was bought in 2006 as part of a $7 million deal.

At least a dozen successful companies have been built around the purchase of a forgotten drug.

And Ramaswamy has quickly established a track record: Roivant Sciences’s 76 percent stake in Axovant and its Alzheimer’s pill, code-named RVT-101, has produced a 20,000 percent paper return on its initial $5 million investment. Before that, Ramaswamy turned a $8 million purchase of several drugs to treat the liver virus hepatitis B into a $110 million stake in Arbutus BioPharma, a 1,275 percent paper return. In May, Roivant scooped up a drug for psychosis for $4 million from Arena Pharmaceuticals. It also partnered with a Duke University group with a track record for inventing rare-disease drugs. A whirlwind of such deals has made Ramaswamy, a member of the Forbes 30 Under 30 list, biopharma’s youngest chief executive. He may soon be its youngest billionaire.

Forbes estimates that Roivant is worth $3.5 billion, making its Millennial founder’s 20 percent or so stake worth some $700 million. Ramaswamy, who just turned 30, has bigger aspirations. Roivant, he says, will become the “Berkshire Hathaway of drug development”.

Vivek Ramaswamy is any parent’s dream. He is the eldest son in a family of South Indian immigrants. His father was a company man at General Electric, and his mother worked for Merck and Schering-Plough as a geriatric psychiatrist. Ramaswamy was valedictorian at his high school in Cincinnati, an accomplished pianist who played for the Alzheimer’s patients his mom treated and a nationally ranked junior tennis player whose serve could hit 120 mph.

At Harvard, he was chairman of the Harvard Political Union, worked in the lab of renowned stem cell scientist Douglas Melton and took the stage as a libertarian hip-hop artist named ‘Da Vek’. He also co-founded a company, StudentBusinesses.com, which connects startups, advisors and investors, and sold it to the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, which offers it as a free tool renamed iStart.

But Ramaswamy, who graduated in biology, wanted to change the world. He thought of becoming a doctor or a researcher but didn’t want to spend another decade in school. Then he discovered hedge funds, where a 25-year-old can control hundreds of millions. “When I first told my parents about it, they thought I was going into the landscaping business,” says Ramaswamy.

He scored an interview with Dan Gold, who runs $3.5 billion QVT Financial in New York. “He was bright but also hungry,” recalls Gold. They wound up talking for several hours, discussing Ramaswamy’s senior thesis on the ethical issues involved with using stem cells to create human-animal hybrids.

He became an analyst. With his biology training, Ramaswamy understood early the potential of drugs to treat hepatitis C, a blood-borne liver virus that afflicts at least 3 million Americans—and his resulting trades for QVT amazed Wall Street. In 2008, Ramaswamy started buying shares of Pharmasset, in Princeton, New Jersey, at about $5 on a split-adjusted basis and was one of the top shareholders when Gilead bought the company for $137 a share, or $11 billion, in 2011. Rama- swamy repeated the performance with Inhibitex, which was purchased by Bristol-Myers Squibb for $2.5 billion in 2012, making 25-fold QVT’s initial investment. At 28, Ramaswamy was made a QVT partner.

On the side—“for the intellectual experience”—he earned a law degree from Yale. He was “one of the few people who did all the reading,” says Yale law professor David Grewal. “He always came to class ready to argue—he likes arguing.”

Such critical thinking resulted in an epiphany: Ramaswamy noticed there were many, many forgotten drugs that he would have liked to invest in but couldn’t. They were trapped in big pharmaceutical firms that had shelved them for strategic or bureaucratic reasons, or in small biotechnology firms that had to focus all their resources on a single product. Speaking at a Down syndrome fundraiser in North Carolina, he laid out the moral case: “There is probably a promising drug candidate that has already been discovered for the treatment of Down syndrome that is sitting on the shelf of some drug company.”

When Ramaswamy struck out on his own last May, QVT and Dexcel Pharma, an Israeli firm that had no- ticed his track record, backed him to the tune of nearly $100 million. He named his company Roivant—he’s fond of the acronym “ROI”—and set out to deliver high returns on investment from a relatively shabby rent-an-office building for startups in mid-town Manhattan. His small, disparate crew, including some young Ivy League graduates and two biotech heavyweights—Larry Friedhoff, 66, the former head of R&D at Eisai and Andrx, and William Symonds, 48, who had been instrumental in the success of Pharmasset and Gilead—occupied a disjointed space where they couldn’t even sit together. No matter. “To be honest, if I was going to bet on a human to win at something,” says Symonds, “I would bet on Vivek.”

The Pharmasset connection served them well. That company thrived because of a single hep C pill, called sofosbuvir, or Sovaldi, which, after being purchased by Gilead, had the best launch of any medicine ever, generating $12 billion in its first year. The drug was rumoured to be named after Mike Sofia, the chemist who invented it. Now Sofia had started a new company, OnCore Biopharma, to fight a different kind of hepatitis, hep B. Thanks to vaccination, it’s less of a problem in the US, but it kills 780,000 people a year, largely in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, by causing liver complications like cancer.

As with hepatitis C and HIV, treating hep B would require multiple drugs in combination. Yet promising candidates were spread across the pharma universe, another market failure. So Ramaswamy took control of OnCore and executed three more deals to bring four other forgotten drugs into the pipeline. He took the faster route to going public by merging OnCore into Tekmira, a Nasdaq-listed company developing more antiviral drugs, and renaming it Arbutus. In the course of seven months, Ramaswamy had turned an initial $8 million investment into $110 million of market value.

With this instant success, Ramaswamy was poised to think bigger. Everyone knows that Alzheimer’s is a scourge—it’s forecast to afflict 13.8 million Americans and cost the US economy $1 trillion annually by 2050. But it’s also a pharma death trap. Between 2002 and 2012, researchers tested 244 Alzheimer’s drugs, and only one made it to market—a 99.6 percent failure rate.

Ramaswamy’s research chief, Friedhoff, had led the development of Aricept, the best-selling Alzheim- er’s drug ever, with $4 billion in peak sales. When his young boss told him he was interested in the cast-off Glaxo drug, Friedhoff told him to find something less risky than Alzheimer’s. But Ramaswamy kept hearing that the drug was worth a look. “When people have asked me over the years, ‘Are there any drugs that should have gone forward, that should get another chance?,’ this one comes to mind,” says Rachelle Doody, a top Alzheimer’s researcher at the Baylor College of Medicine who worked with the drug when it was Glaxo’s.

Symonds set up a meeting with Atul Pande, Glaxo’s senior vice president in charge of neuroscience research. They found Pande was effusive about the drug (so much so that he would eventually leave to become an Axovant director), which had been a victim of Glaxo’s technical retreat from neuroscience. In 2010, Glaxo had announced that it was mostly going to exit the field, and any lingering interest in Alzheimer’s drugs would focus on reversing the disease instead of relieving symptoms.

But when Ramaswamy looked at the data for the drug, he saw a winner. It had failed the first three clinical trials that tested the drug alone. But Ramaswamy and many experts believe animal data that show RVT-101 will work far better when paired with an older drug like Aricept. A fourth study offered evidence of that, but the trial failed because Glaxo picked the wrong endpoint. In the fourth study, RVT-101 reversed Alzheimer’s patients’ symptoms to where they had been more than six months before, but then the disease’s merciless progression continued. Still, if the next trial can show the same benefit—or even a slightly weaker one—that would be enough to get the medicine approved. More comfort: Another drug being developed by the Danish drug firm Lundbeck targets the same brain receptor as RVT-101 and shows similar results. Friedhoff, Roivant’s renowned Alzheimer’s expert, was convinced.

Now the only problem was getting the drug out of Glaxo. Eventually, Ramaswamy got the terms he wanted: Just $5 million upfront but also $160 million in milestones and a 12.5 percent royalty on sales. Basically, he gives big companies a chance to win big—if RVT-101 ever becomes a $1 billion seller, the royalties would boost Glaxo’s earnings by 2 percent. With the drug in hand, Ramaswamy decided to spin out Axovant—the company built around RVT-101 as its only asset—hitting up his old hedge fund peers. “He comes from our world,” says Peter Kolchinsky, who runs $1.8 billion RA Capital. “I saw the data, and I knew that if I didn’t say yes, it was going to go to someone else.” Kolchinsky’s condition: He wanted a big position. He bought $75 million worth, his fund’s largest holding, at the IPO price. So did hedge fund Visium Asset Management. Mutual fund managers like Capital Growth and Janus also bought in. In order to signal to investors that the hedge funds would not take advantage of a first-day pop, the funds agreed to hold their shares for at least 90 days—a costly move, since Axovant shot up nearly 100 percent after its IPO in June, but then fell below its offering price. “The markets can fluctuate, but the fundamentals haven’t changed,” says Kolchinsky.

A decade ago, raising $100 million in a biotech offering was unheard of. Today it’s commonplace. In January, venture capitalists put $450 million into Moderna Therapeutics, a company with fascinating science but no drugs in testing, and a few months later they gave $217 million to Denali Therapeutics, another company focussed on Alzheimer’s as well as Parkinson’s. The public markets are also bubbling. In July, NantKwest, the latest company from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, raised $207 million at a $3 billion valuation based on its new cancer-killing cells.

Amid this rush of money, Ramaswamy’s big Alzheimer’s IPO spooked investors. After all, for Ramaswamy’s team, Axovant is a no-lose investment, given the minuscule price it paid Glaxo for RVT-101. But public investors understandably fear being set up as greater fools. This doesn’t bode well for the young dealmaker’s grand scheme. Says Ramaswamy, “It’s ironic because it will be the same capital-efficient approach that brought RVT-101 that will be our model for building our business going forward.” Axovant speculators will have to wait until 2017 before they hear of any new RVT-101 data for Alzheimer’s. Under the best possible scenario, real benefit to Alzheimer’s patients is years way. Clinical trials are notoriously difficult even when the remedy seems to work—and expensive. It may ultimately take $135 million to run the trial on RVT-101.

But it would be a mistake to get stuck in the weeds of Roivant’s Alzheimer’s efforts. Ramaswamy’s approach is long term and broad in scope. In many ways, he is taking a page from the career of Michael Pearson, the billionaire chief executive of Valeant Pharmaceuticals. In the early 2000s, when drug approvals were approaching an all-time low, Pearson came up with a financial engineering strategy that produced a company now worth $80 billion, using a tax shelter to buy drugs that were underperforming and cutting costs, including R&D, to the bone.

It’s a successful approach that has won Wall Street approval, most notably from Bill Ackman, whose Pershing Square hedge fund owns 5.7 percent of Valeant. Ramaswamy is doing something similar, except he’s betting that biotech is so productive at inventing new remedies that he can find forgotten drugs for cheap and fund more R&D, not less. “It’s a specialty biotech that will create value out of products that are yet to reach the market rather than extracting value out of dwindling revenue streams,” he says. Ramaswamy has something Pearson lacks: Charisma. “I tend to like people who are a little bold and get things done, but do it in a way that isn’t obnoxious,” says Brent Saunders, the chief executive of Allergan. “I think Vivek fits the bill so far.”

Like Pearson, Ramaswamy has an innovative strategy for growth. Even if RVT-101 fails, Axovant has used it to raise nearly $200 million it can spend on other compounds. Meanwhile, Ramaswamy’s Roivant vehicle, still sitting on nearly $100 million, will be buying other drugs, which he can spin off or house in silos, letting him tailor and incentivise specialised teams around each effort. This approach will allow him to spread his bets in fund-of-fund fashion, as well as give potential investors pure-play action in an array of therapeutic areas.

Ramaswamy’s youthful enthusiasm and hubris haven’t gone unnoticed. But however the drugs perform, there’s real financial innovation here, with potential to save and improve countless lives, whether through him or others who emulate the model. And that’s something a biotech bubble, whenever it bursts, can’t wash away.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)