What's Donald Trump really worth?

He's a roguish charmer. He's a pugnacious bully. He tells it like it is. He fibs when necessary. And for 33 years, he's been building and boasting his way higher on the Forbes 400. If you want a unique window into what makes the most paradoxical presidential candidate in a generation tick, you just need to answer this simple question

For a man who has driven the national news cycle pretty much every day for the past four months with his disruptive presidential campaign, Donald Trump works out of an office suite that is shockingly calm. No yelling, no running, no extraneous advisors or flunkies—it has the sleepy, orderly pace of an accounting firm in Boise, Idaho, albeit one with a taste for mirrors, regal gold and lots and lots of framed articles about Donald Trump.

On this Monday in late September, only the most important of the important requests seep into the corner office. “I have the Stephen Colbert pre-interview,” one of his assistants reports. Responds Trump: “Would you do me a favour? We’ll call them back.” His daughter Ivanka apparently wants to follow up about something. “Little Ivanka,” he smiles, before relaying that he’ll get back to her later. Someone from 60 Minutes, which will tape Trump the following day and broadcast its interview with him that Sunday, asks to talk. The iconic show will have to wait, too.

The most in-demand person on the planet has gone into hold-all-my-calls mode for nearly two hours to sit down with Forbes and tackle, piece by piece, a subject that he cares about to the depths of his soul: How much Forbes says he’s worth. Since The Forbes 400 list of richest Americans debuted in 1982, the dynamism of the US economy and the hand of the grim reaper have resulted in exactly 1,538 people making the cut at one time or another. Of those 1,538 tycoons, not one has been more fixated with his or her net worth estimate on a year-in, year-out basis than Donald J Trump.

Trump’s valuation this year holds extra importance, of course, due to his audacious second act: His highly unlikely—but no longer inconceivable—path to the presidency. Trump has filed statements claiming he’s worth at least $10 billion or, as he put in a press release, TEN BILLION DOLLARS (capitalisation his). After interviewing more than 80 sources and devoting unprecedented resources to valuing a single fortune, we’re going with a figure less than half of that—$4.5 billion, albeit still the highest figure we’ve ever had for him.

“I’m running for president,” says Trump. “I’m worth much more than you have me down [for]. I don’t look good, to be honest. I mean, I look better if I’m worth $10 billion than if I’m worth $4 billion.”

To The Forbes 400 crowd, perhaps. But when pushed, even Trump concedes that, for voters, the difference between $4 billion and $10 billion is as abstractly irrelevant as a star that’s either four billion or 10 billion light-years away. Ultimately, Trump’s beef with our numbers is driven by Trump: How his peers view him and, more acutely, how he views himself. It always has been. The paradoxical Trump that now transfixes American political culture is the same one that The Forbes 400 has been dancing with for 33 years. And the history of his net worth fixation opens windows into Trump the entrepreneur, the candidate and the person.

The inaugural edition of The Forbes 400 in 1982 introduced all sorts of names into the national discourse, and many of these previously under-the-radar tycoons fought back against their newfound recognition. Florida land baron William Graham asked Forbes to move his decimal one place to the left. The lawyer for an Oklahoma titan offered to dig up a replacement if his client was taken off the list. Then there was New York real estate developer Donald Trump, 36, whose very first entry, which estimated that he and his father, Fred, equally split a $200 million fortune, ends thusly: “Donald claims $500 million.”

Trump has measured himself by lining up assets against liabilities for his entire adult life. In his 1987 bestseller, The Art of the Deal, he recalled his net worth when he graduated from college (“perhaps $200,000,” probably the only time he ever low-balled his stash), publicly memorialising a benchmark for measuring his future success.

He added three and almost four zeroes to that figure during the 1980s as a tabloid caricature. As ‘The Donald’, he honed the art of net worth lobbying. Financial summaries would arrive at the Forbes offices, often on gilded Trump-embossed letterheads for extra pop. “We soon learnt to take the number he threw out to us for his net worth, immediately divide it by three and refine it from there,” remembers Harold Seneker, who ran The Forbes 400 for the first 15 years of its existence. And, indeed, the “divide by three” rule seemed to hold throughout the 1980s, including 1988, when we pegged him at an even $1 billion. The Donald, not content with his new billionaire status, countered with $3.74 billion.

As the years went on, Trump adopted a more personal touch, via phone calls and lunches, enlisting his longtime CFO, Allen Weisselberg, in the process. Good with names and dishing out tidbits like candy, Trump can be quite charming. The first time I interviewed him for Forbes, more than 20 years ago, he called me from a hospital waiting room. His second wife, Marla Maples, had just given birth to a daughter—Tiffany, he confided.

Trump’s motivations for inflating his net worth were partially driven by dollars and cents. “It was good for financing,” Trump now acknowledges, echoing what other developers have told us over the years: That slapping a high Forbes 400 estimate on a banker’s desk can sometimes help secure bigger loans and better rates. When I was a $27,000-a-year cub reporter on The Forbes 400, the largest strip-mall developer in Texas, the late Jerry J Moore, offered me a six-figure PR job “with lots of golf” if I would only nudge his number closer to billionaire status.

Trump was also a pioneer at turning his eponymous developments into a luxury-brand umbrella. His financial success defined what the brand ‘Trump’ meant. When a reporter named Timothy O’Brien came out with a book, TrumpNation, in 2005, a huge excerpt appeared in the New York Times alleging that Trump was worth $250 million tops (versus the $2.7 billion Forbes estimated and the $7.8 billion Trump fancied). Trump sued for a fantastical $5 billion in damages. While O’Brien’s methodology was faulty, the case was dismissed. But Trump’s lengthy deposition, obtained by Forbes, underscores the connection he sees between his wealth and his brand. “I wasn’t doing poorly then, but I was perceived,” Trump testified. As a result, “I think that article hurt my brand, and it hurt me.”

As in personally. “For the record, he regards the 400 as something of a bible,” says a note in Forbes’s Trump file, following a 1990s power lunch with Forbes 400 staffers at New York’s Gotham Bar & Grill, “and is convinced others do, too.”

When fully engaged, the Donald Trump net worth experience is a full show-and-tell affair, complete with sketches of buildings, aerial photography and guided tours. The latter starts in the Trump Tower gym, which looks like a Sheraton workout room, save for the staggering view, and is somehow supposed to persuade us to juice the $530 million we ascribe to The Donald’s holdings within his signature building by a factor of five or six. The only exercising going on occurs when Trump’s campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, hustles in and whispers urgently in his boss’s ear.

Trump turns to me. “Scott Walker just quit the race,” he says, referring to the Wisconsin governor, who, until Trump upended everything, had been considered a top-tier presidential hopeful. “I think that’s good.” Surely, every other candidate is convening a war room, figuring out how this changes the landscape. Not Trump. “Not much to divvy up,” he shouts at the retreating Lewandowski. “See if you can get his one vote, Corey.”

Trump would rather take me up to his three-storey penthouse and prove it’s surely worth twice the $100 million value we put on it. An offer to see the over-the-top Versailles-in-the-sky needs no arm-twisting, but Trump sells it anyway: “I’ll show you the first floor of my apartment, which I’ve never done before—I don’t do that.”

Except he has. To Access Hollywood. And Newsweek. And Extra. And a Forbes photographer way back in 2000. Heck, his 60 Minutes interview would take place in the first floor of the penthouse the next day, to be shared with 15 million people on Sunday. Trump has never let small details get in the way of good pitch.

In 1990, however, Trump hyperbole blew back on him. The New York real estate market was crashing, his Atlantic City casinos began struggling, and he was underwater with his new toy, the Trump Shuttle airline. In 1989, Forbes had his net worth at $1.7 billion. By spring 1990, Forbes figured it was $500 million at best. By that fall, the overleveraged Trump was “within hailing distance of zero” and dropped from The Forbes 400.

As with today, Trump sat in his corner office and provided a rebuttal. It wasn’t very convincing. “I’m going to show you cash-flow numbers I’ve never shown anyone before,” he said back then, in familiar spin mode—but he folded the pages to obscure the final column. And while he insisted he was worth between $4 billion and $5 billion, Forbes obtained records that Trump had submitted to a governmental body, professing that as of May 1989, his net assets were only $1.5 billion—one-third of what he had told us and even a bit less than the number Forbes, which strives for conservative estimates, had arrived at the previous year.

The fibbing was more brazen when they delved into specifics. In 1988, Trump sent Forbes a document listing his personal residences—including Mar-a-Lago, his Palm Beach mansion—with a total net value of $50 million. At the same time, sworn statements placed their total asset value at $30 million, along with a debt load of $40 million—a net liability. Trump also said he owned $159 million in stock and bonds, all unencumbered. But documents filed with the SEC showed that he borrowed big-time to buy the stock, which subsequently dipped.

Trump did not like this challenge to his reputation. He published an essay for the Los Angeles Times syndicate: “Forbes Carried Out Personal Vendetta in Print”. He argued that the “willfully wrong” piece was driven by the desire to sell magazines and damage his reputation. He told ABC’s Sam Donaldson that “Forbes has been after me for years, consistently after me.”

“Forbes is doing everything they can, possibly, to make me look as bad as possible.”

Fast-forward 25 years. Trump is famously loath to apologise. (Ask John McCain.) But he does now admit the obvious: That he stretched the facts in those dark days. Then, without irony, he criticises Forbes because “you were actually high”. Adds Trump: “I deserved to be off [the list].”

“By the way, I never complained.” When reminded that he did indeed complain, Trump shrugs, “Yeah, whatever.”

Other than in some version of a joke about people who walk into a bar, the pope and Donald Trump have probably never appeared in the same sentence. But providence intervened at the end of September when Pope Francis, on his first visit to America, decided to hold evening prayers at New York’s St Patrick’s Cathedral—and the papal planners decided that the formal procession down Fifth Avenue, led by the Popemobile, would commence below Trump Tower.

And so Trump asks if we can truncate a Forbes cover shoot in favour of an impromptu viewing party. As the Holy Father’s motorcade approaches, Trump leads a half-dozen people down to a fifth-floor corner balcony attached to his campaign headquarters, the “best-located political floor in history”. At $2,170-per square-foot (or $10,580 if you take Trump’s number), no exaggeration there. Yet, aside from posters and a forlorn table or two, it’s completely dead. The richest man ever to run for president oversees a skeletal operation, based on gut instincts and free media. “I literally have spent $543,000 on my campaign,” says Trump. “Other people have spent $20 million, $25 million already. Like Bush and all these people. They’re spending a fortune.”

The famous Popemobile idles perhaps 50 feet under us, waiting for its passenger. (Trump isn’t a fan of its open sides: “That’s a dangerous-looking sucker.” And he’s even less impressed by the very modest, un-Trumplike Fiat that Francis is arriving in. “I don’t like the little car. He’s trying to be ‘of the people,’ but I don’t know. It just doesn’t look right.”)

Also 50 feet below: Thousands of people who’ve lined Fifth Avenue for a papal glimpse. Given the pool of New York City Catholics and the visit of an Argentinian pope, they’re roughly half Latino. (“Fran-cis-co, Fran-cis-co,” went the cheers as the pontiff approached.) Not exactly Trump’s base. For once, Trump wasn’t looking for attention: “I’ll look like an idiot. This is the pope’s day.” But lately, especially at 6-foot-3, with that mane, he doesn’t have a choice. So Trump waves from his perch, an orange-haired Juan Perón.

Jeers and whistles ensue. Undaunted, Trump turns to me. “Ninety percent positive,” he says. “Ninety percent is pretty good. You’ll take that in an election right away.” Did Trump hear what everyone else heard, yet immediately spin toward the absurd? (While there was a smattering of applause, the catcalls clearly carried the day.) Or did he just hear what he wanted to?

In some ways, it doesn’t matter. Colleagues of Steve Jobs famously described his “reality-distortion field”—his ability to see what he wanted to see and then will the delusion into truth. Way before that, another master capitalist, Andrew Carnegie, declared that “all riches, and all material things that anyone acquires through self-effort, begin in the form of a clear, concise mental picture of the thing one seeks.”

Trump has a healthy dose of this gene. In the O’Brien deposition, taken in 2007, Trump declared that his estimates of personal net worth were subject to day-to-day whims. “Even my own feelings affect my value to myself,” he said. When asked to specify, he described it as “my general attitude at the time that the question may be asked.” And if that general attitude is negative? “You wouldn’t tell a reporter you’re doing poorly.”

As the pope rolls below Trump’s perfect eyrie, Trump’s general attitude is extra-positive. “You see what I mean about this real estate? This is really a great piece of real estate. Boy, do we have a good location.” During an earlier conversation, Trump at different times said he could sell his stake in Trump Tower for $2 billion or $2.5 billion or $3 billion. When an extra $1 billion is created that easily (much less the difference compared with our appraisal for the building of $530 million), it’s easy to see how he conjures $10 billion.

This just-do-it business worldview provides a feasible explanation to what’s perhaps the greatest riddle surrounding candidate Trump: How can someone who’s quite clever and smart (as he’ll quickly remind you) also promote know-nothing, sometimes dangerous bunk, whether a disproven link between vaccinations and autism or the Obama-might-have-been-born-in-Kenya lie?

And by keeping his message simple and repeating it with conviction over and over, Trump has the ability to shape facts. When Trump appears on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert the following day, the liberal host states that Trump is worth $10 billion, with nary a caveat.

Since Trump’s return to the list in 1996, he has had a more nuanced relationship with The Forbes 400. From the Forbes side, the policy channels Reagan: Trust but verify. Trump shares more information than almost anyone else on the list, and we accept the basics. But without proof of ownership or debt or specific assets, we err on the side of caution. Usually Trump’s team shows us their liquid investments. Last year, we saw documentation for cash and cash equivalents of $307 million. Now they’re claiming $793 million but are unwilling to show it. So we play it safe with $327 million (grossed up to include proceeds from the Miss Universe sale.)

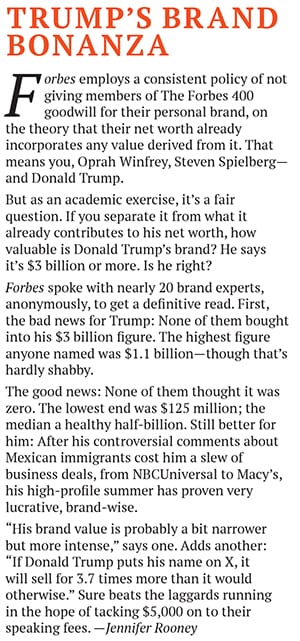

And as for the worth of the Trump brand, which his camp often values in phantom billions, we now consistently give it a value of zero. We say the value of it to these deals is already built into his net worth and don’t assign it a present-day theoretical value to future deals.

But Trump and his team also corrected us on things like Niketown’s square footage (too low) and debt loads at Trump Park Avenue and the Old DC Post Office ($170 million down to $8 million). We also, at his urging, reanalysed Trump Tower and the Doral golf course. All told we added $700 million to our initial net worth estimate.

Meanwhile, Trump, as is his wont, talks tough. “He’s an alpha male—in spades,” says Phil Ruffin, a fellow Forbes 400 member whose Las Vegas partnership with Trump has yielded each man $96 million. “He’s strong. He’s competitive—extremely competitive.”

“I think you’re trying to make me as poor as possible,” says Trump, whose campaign filings claim that this year alone his worth has risen from $8.7 billion ($3.3 billion of that from brand goodwill) to more than $10 billion. Over the course of our interviews, he raises that to “much more than 10 billion” and says that another “respected magazine that’s coming out” is going with $11.5 billion.

“You’re gonna look bad,” he adds. “And look, all I can say is Forbes is a bankrupt magazine, doesn’t know what they’re talking about. That’s all I’m gonna say. ’Cause it’s embarrassing to me.”

My overarching question for Trump is a simple one: Does he think Forbes uses a different methodology to value him than it uses for every other real estate titan on The Forbes 400? “Yes, I do,” he responds. “Yes, I do.”

Really? Why? “Because I’m famous, and they’re not. Because when [Richard] LeFrak had dinner at Joe’s Stone Crab, he calls me up and he says, ‘Could you help me get a reservation?’”

But make no mistake—Trump cares. Over the past few years, he’s taken to sending handwritten notes to Forbes 400 reporters, atop articles favourable to him. (“Insurance cos + other developers put this much money in—not me,” he scrawls in Magic Marker in the margins of his personal issue of Golf, Inc., which he sends over.) On an evening when he should have been boning up for 60 Minutes and Colbert, he calls me to clarify the status of one mortgage on one building in his portfolio. And on Monday, he announces his tax plan, his assistant scans and emails a personal note from him suggesting ranges for his brand value.

And at the end of our last interview, he asks if I have a headline in mind for the story. I tell him, truthfully, that I don’t. Then I ask him what he would suggest. The populist who wants to be president, with the billionaire’s bank account and the papal perch, barely pauses to think: “The King.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)