World's Billionaires: Masayoshi Son's last laugh?

Between the WeWork debacle and the coronavirus, the markets have deemed his $100 billion Vision Fund largely worthless. But the world's most important investor over the past three years, SoftBank's Masayoshi Son, has other assets, a track record—and a plan

Image: Tomohiro Ohsumi / Getty Images

Image: Tomohiro Ohsumi / Getty Images

With a flurry of slammed black SUV doors, SoftBank Founder Masayoshi Son and his entourage duck into the hush-hush private space within America’s top seafood restaurant, Le Bernardin, the Japanese billionaire easy to mark by the metallic-gray Uniqlo down jacket he wears over his suit.

The man known simply as Masa has gathered around twenty of the world’s largest asset managers in Midtown Manhattan on this day in early March. He hands over a colorful tote bag he’s using instead of a briefcase and assumes the empty chair at the dead center of one side of a large three-sided table. The day before, he’d spoken to a larger group of investors, but he’s billing this morning as an exclusive “Pre-IPO Summit,” and he’s drawn a multitrillion-dollar audience, including BlackRock’s Larry Fink, who sits next to him.

“Despite people’s view that SoftBank might be struggling, we continue to grow,” Son tells them. “Don’t think about the past.”

Easier said than done. SoftBank’s $100 billion Vision Fund is surely the most-scrutinised in the world, and for good reason. Over the past three years, Masa has made a dizzying number of huge, bold bets—88, to be precise—at huge, bold valuations. Things haven’t gone exactly as planned. First, there was Uber, which the Vision Fund backed late, leaving it hundreds of millions underwater. And then WeWork, into which SoftBank has pumped more than $10 billion since 2017, and which cratered since it withdrew its much-maligned IPO plan following the sloppy exit of its self-centered, self-dealing founder, Adam Neumann. A “tough time,” Masa concedes to the group. The previous day, he had given a longer explanation to Forbes privately: “We paid too much valuation for WeWork, and we did too much believe in the entrepreneur. But I think even with WeWork, we’re now confident that we put in new management, a new plan, and we’re going to turn it around and make a decent return.”

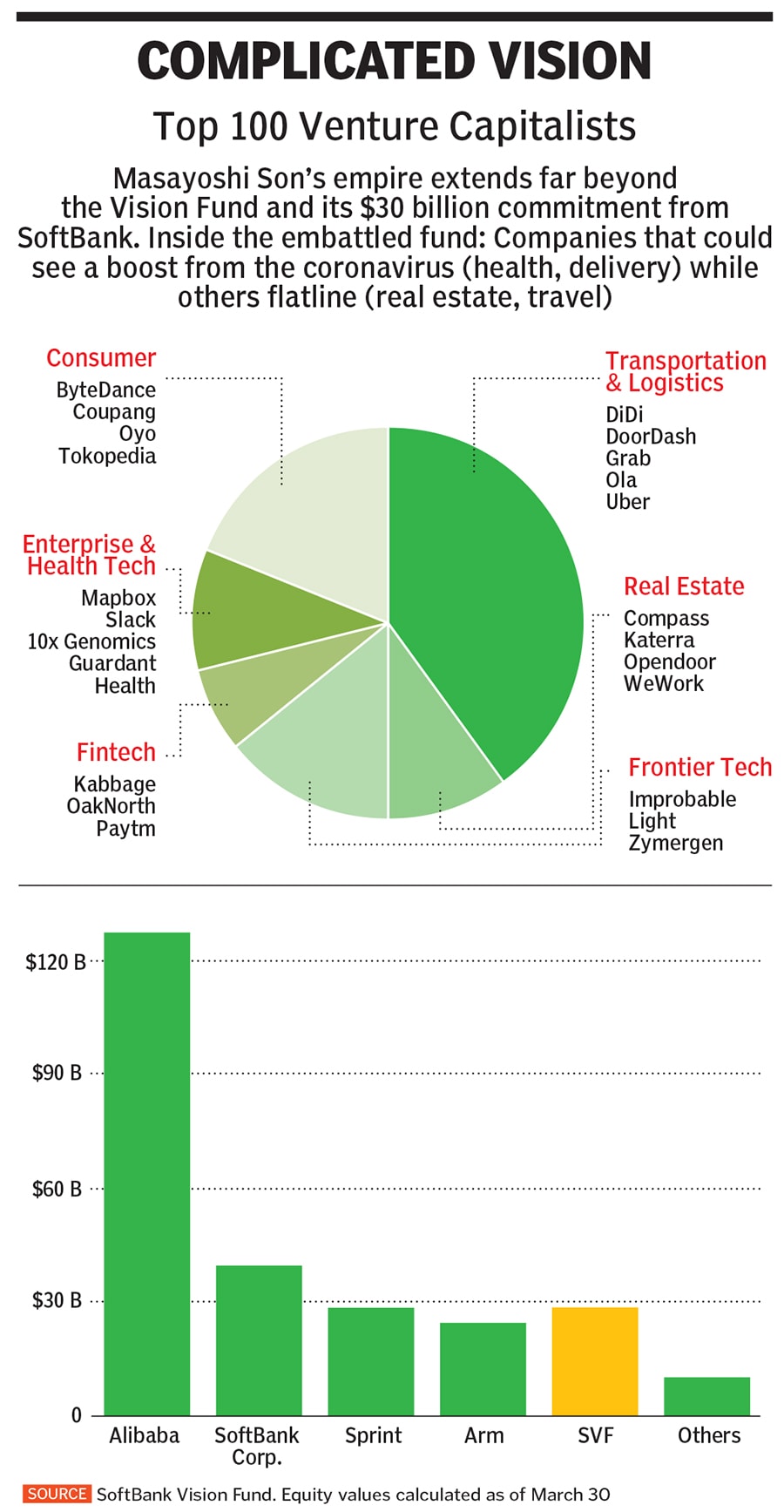

To try to pivot, Masa invokes the past. Specifically, his career-clinching deal and SoftBank’s crown jewel, the $20 million check he wrote into Chinese marketplace Alibaba—now valued at more than $120 billion. “Alibaba the first 10 years had almost zero revenue,” Son tells them. “But once it started generating, it popped up dramatically.”

To buttress that point, he trots out nine of his portfolio companies for a 20-minute presentation from each. “The companies today have an initial move ahead of everyone else,” Son says. “It’s the beginning. I want you to see and to feel what is going to happen.” There are indeed some dandies there, including TikTok owner ByteDance and Korean ecommerce leader Coupang.

SoftBank’s Rajeev Misra (left) and Masayoshi Son (middle) with their key Vision Fund backer, Yasir Al-Rumayyan, who is the governor of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign fund

SoftBank’s Rajeev Misra (left) and Masayoshi Son (middle) with their key Vision Fund backer, Yasir Al-Rumayyan, who is the governor of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign fundImage: Bandar Algaloud / Saudi Royal Council / Handout/Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

But the elephant in the room isn’t actually in the room—it’s early March, and Coupang is presenting remotely because of the coronavirus outbreak in Asia. The power table, Masa included, seems naively unprepared for the pandemic about to strike. Masa’s prediction about WeWork already looks absurdly wrong—judging by WeWork’s debt prices, SoftBank’s stake there appears to be heading toward zero, or dimes on the dollar in the best case. The Vision Fund as a whole, with its later-stage, higher-valuation investments in the sharing economy, transportation, travel and real estate, looks similarly distressed. Some two weeks after that meeting, SoftBank’s stock trades at a 73 percent discount to its parts’ enterprise value.

Things have changed so quickly that SoftBank’s stock might actually jump if the Vision Fund shut down entirely. When Son recently relented, despite longtime insistence that he wouldn’t, and agreed to divest a portion of SoftBank’s public assets (expected to include part of its Alibaba stake) as part of a $41 billion plan to buy back SoftBank stock and pay down debt, investors rejoiced.

Yes, it showed support for the stock price. But the company also announced that it would be more cautious in making new investments from its fledgling second Vision Fund. “We understand what we need to do in such circumstances,” says SoftBank’s chief financial officer, Yoshimitsu Goto, a longtime Son confidant who speaks with the media even less frequently than his press-shy boss. “I believe Masa does understand the market, too.”

Besides being one of the most extreme investment vehicles in history, the Vision Fund was also a high-speed rebranding exercise. The deal frenzy erased from the public consciousness the fact that SoftBank already holds a bevy of blue-chip assets, and it limited exposure—other than reputational—given that some 70 percent of the Vision Fund money came from investors like the sovereign funds of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, and Silicon Valley heavies like Apple and Qualcomm.

SoftBank still owns British chipmaker Arm and wireless carrier Sprint, set to merge with T-Mobile in April, as well as big stakes in Alibaba and SoftBank Corp., the Japanese carrier it took public in 2018, among others.

And it still has Masa. No one made more riding the dotcom bubble 20 years ago, with the likes of Yahoo and E-Trade; no one lost more, either (99 percent of SoftBank’s market cap, to be exact). His fortune vanished, but his vision was unblurred, and he earned billions back (his current net worth: $16.6 billion). “In the beginning of the internet, I was criticised the same way,” he says. “Even more so than now.

“Tactically, I’ve made regrets,” he continues. “But strategically, I am unchanged. Vision-wise? Unchanged.”

Masa Son spends most of his time in Japan, but he has a pied-à-terre in Silicon Valley in the form of a 9,000-square-foot mansion in Woodside. When he bought it in 2012 for a reported $118 million, it was the most expensive house in America.

Right after his New York swing, Son invited over a mix of portfolio companies, including two newcomers: Blood-testing startup Karius, which raised a $165 million round led by SoftBank in February, and San Francisco–based digital druggist Alto Pharmacy, into which SoftBank just invested $200 million of its own cash.

“I’ll hear something from Masa and my reaction is like, wait, what? That doesn’t make any sense,” says Mattieu Gamache-Asselin, Alto’s CEO. “Then you’ll hear him more and be like, oh, wait, I’m looking at this completely different and wrong, how can I change my perspective? He has this way of making you see the world differently.”

Meeting Son, 62, has long been one of the great rites of passage for ambitious tech entrepreneurs. When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone to the world, it was Son who convinced him to come to Japan, securing exclusive rights to distribute the hit product in the country for three years.

Born in Japan and famously bullied for his Korean heritage, Son moved to California for a study-abroad program and, though he initially spoke no English, passed his college preparatory exam; eventually he transferred to the University of California at Berkeley, where he graduated in 1980. He’d already sold an electronic-translator business to Sharp and made over $1 million importing refurbished arcade machines by the time he went back to Japan the following year to start a business designed as a “software bank,” SoftBank.

After making his bones selling software licenses and operating computer-focused magazines and trade shows, Son returned to the US in a big way in 1996, when he bought tech publisher Ziff Davis and invested a then-record $108 million of venture capital for a 41 percent stake in a fledgling internet business called Yahoo. SoftBank poured billions into dotcoms, winning big with some like E-Trade, and suffering a widely reported billion-plus loss at chipmaker Kingston Technology. For three days at the bubble’s peak, Son has claimed, he was the richest man in the world. Then it all came to an end. By the time the bubble had fully burst, in 2002, SoftBank had lost 99 percent of its market cap, going from $180 billion to just $2 billion.

It wasn’t only Son who lost a fortune: As with his Vision Fund today, many top executives had poured much of their net worth into SoftBank’s stock. “We sat around a table with him and said, OK, what do we do now?” says Ron Fisher, who managed SoftBank’s US investments and is now vice chairman. According to Fisher, though, almost every executive stayed on to weather “a couple of years of real pain” with their boss. “Masa has a unique ability to connect with people,” he says. “He can be incredibly self-effacing and humble in terms of understanding his own shortcomings.”

A cautionary tale by this point, Son spent the next decade-plus bringing SoftBank all the way back. The first step: Patience. Masa stubbornly clung to one particularly dear investment. “I was the most bullish guy about the future of Alibaba, more than the management themselves,” he says. “I think the same will repeat again.” From there, highly complex and levered transactions enabled him to acquire Vodafone’s Japan operations and Sprint Nextel, plus British chip maker Arm Holdings. SoftBank also successfully flipped a stake in mobile game maker Supercell,which developed Clash of Clans. The company kept investing in startups, too, averaging $4 billion or so a year, when in 2017 Son decided to go big again. “The last 20 years, the internet has disrupted the advertisement industry and

retail industry; those are the only two,” he says. “Going forward with the power of AI, it’s going to disrupt every other industry.”

Rajeev Misra, a longtime ally, was tasked with leading the world’s largest-ever fund for private tech investments, the Vision Fund. A controversial but brilliant banker, Misra helped bail out and craft Son’s complex financial transactions of the 2000s at Deutsche Bank. More recently, he’s been accused of spying on and orchestrating smear campaigns against his own colleagues. (Misra denies this: “No, no, I’m an open book, mate. There is no such thing.

We are talking about God’s word, God’s grace to be where we are. . . . It’s the size [of Vision Fund]. If I was out on the street, not investing at Vision Fund, no one would be saying that.”)

Misra signed up the investors, led by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, for a record $100 billion fund with orders to spend no less than $100 million to amass large stakes in emerging market leaders of Son’s AI-powered new order. Some, like cancer researcher Guardant Health, had clear connections to the technology. More, like Indian commerce company Flipkart, ride-hailing app Uber and work software business Slack, were the tools Son imagined would be most needed in a world dominated by AI interfaces and autonomous cars.

“Twenty years ago, people were saying, Amazon, why is it an internet company? It’s just a retail company, right?” Son says. “Today, people say, oh, it’s just transportation.

It’s just real estate. It’s other obvious things, with AI used only a little bit. But you have to understand this is just the beginning.”

It makes sense long-term. But right now, it seems quite frothy. So even before announcing it would dial back new startup investments, SoftBank started telling companies to focus more on profits over hyper-growth, and to consider layoffs, following the WeWork debacle. “No rescue package,” Son said in his earnings presentation in February, but Misra says Vision Fund has reserved $20 billion to invest in its promising portfolio companies and has reportedly sought out another $10 billion to help those running out of funds. “We can invest in the next two years at very low cost,” Son adds. “This will give us the best opportunity.”

Some tough love began immediately. It pulled back from a $3 billion commitment to buy Neumann and other early WeWork investors’ and employees’ WeWork shares, arguing conditions of the deal were not met. It withheld a cash installment from direct-to-consumer retailer Brandless, which then shuttered. Companies like real estate unicorn Compass and small-business loan provider Kabbage have recently turned to furloughs and layoffs. SoftBank allowed another, satellite internet startup OneWeb, to file for bankruptcy even after previously investing about $2 billion. More will go under quickly. “I would say 15 of them will go bankrupt,” Son says.

That’s OK, he adds, as long as a similar number of 15 or so companies break out. SoftBank insiders claim that if the fund can return $150 billion it can still pay back its limited partners their principal and guaranteed 7 percent annual returns, and still eke out a profit. So resources will be deployed toward clear winners. Vision Fund partner Lydia Jett says she and her colleagues have a new focus: To help portfolio companies renegotiate with lenders and landlords, rebalancing budgets and balance sheets, and learning from its Asian portfolio companies that face the worst of Covid-19 first. “There’s a lot going on to help these companies work their way through what will be a long, long journey,” she says.

Outside SoftBank, much of Silicon Valley scoffs at the authenticity of such moves, or questions whether they’re too little, too late. “I think SoftBank has a challenge,” says Ilya Strebulaev, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business who has studied startup unicorns. “Their challenge is that they are enormous.” With Vision Fund’s investment profile—its average first cheque runs more than $400 million, and positions can run into the billions, as with WeWork and Uber—the fund is pushed toward noisy, wide-open categories within tech. The large cheques themselves can encourage a lack of discipline as startups believe more money is always available. And when high-growth, high-spend companies are told to slow down and hoard cash, they may find their management teams ill-suited for the shift.

“SoftBank is considered a blight on the ecosystem, not a saviour,” says Duncan Davidson, a partner at Bullpen Capital, an early investor in Wag, an on-demand dog-walker app in which SoftBank invested $300 million—and eventually sold back to the company at a loss. “The whole industry would be happier if they had never shown up.”

While the Vision Fund is arguably the largest “growth” play ever, the irony is that SoftBank itself is now a value stock. For several years, Son has sparred with analy sts on earnings calls about the discount investors apply to SoftBank’s stock relative to its assets, which implies that public-markets investors value Vision Fund at less than zero dollars. The company’s Alibaba stake alone is worth more than SoftBank’s market cap. As freebies, you get holdings in Arm, its Japanese wireless carrier and Sprint. Plus whatever can be salvaged from the Vision Fund.

“People keep talking about the Vision Fund, the Vision Fund, but you’ve got to look at the size,” says Marcelo Claure, the former Sprint chief executive who is now SoftBank’s COO. “Alibaba can make us more in one week than the entire WeWork investment.”

Yes, WeWork again. The ultimate price is more than the multibillion-dollar loss. It crippled the idea of Masa as a contrarian genius, as opposed to somebody who got duped by a pot-smoking, governance-challenged time-share salesman. Says Masa: “It’s always difficult. It’s not science, it’s art. You get excited with an entrepreneur who seems great but does not necessarily deliver a great return.”

Public-markets investors aren’t irrational by nature, argues Pierre Ferragu, an analyst at New Street Research. They can do the math. SoftBank today doesn’t have the market’s full trust. “The market is afraid of WeWork and Uber being only the beginning of a more general issue,” says Ferragu, who himself is bullish on SoftBank’s shares. “They’re worried SoftBank Group is run by a ‘lunatic,’ Masa, who is going to keep doing that until he doesn’t have a penny left.” Ferragu and other analysts were heartened by SoftBank’s March announcement to buy back shares. But Moody’s downgraded its rating for SoftBank by two notches deeper into junk. (SoftBank has requested that Moody’s stop rating its debt.)

In doing this math, Son has held recent discussions with investors including Elliott Management, the activist fund led by Paul Singer that’s amassed a multibillion-dollar position in SoftBank and demanded such a buyback, among other reforms. One of the options even included taking all of SoftBank Group private, though a source with knowledge of those discussions says that given the massively complex regulatory and structural complications, it’s not considered viable.

What’s not in dispute: At SoftBank and even Vision Fund, it’s Masa calling the shots. As the largest shareholder by far, he controls SoftBank, and he sits as one of three members of the Vision Fund’s investment committee, with final say over deals. This is his game to win or lose, and history will judge accordingly: Is he the ultimate escape artist, readying his third act? Or a bubble chaser who deserves the discount the market attaches to him?

Son lately has been fond of presenting people with Rorschach-like images to drive home the point of perspective. “Look at a shadow,” he says. “Even within 24 hours, the length of your shadow differs dramatically, even though your height in 24 hours is unchanged. People get scared or overconfident looking at the length of the shadow.” Over the next few months, Son will find out if it’s sunset or sunrise.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)