Xiaomi's Lei Jun: The Steve Jobs of China

Xiaomi's Lei Jun built one of the world's most valuable private tech companies by mimicking (and undercutting) the iPhone. Now he's going directly after Apple itself

As a startup CEO, Lei Jun prided himself on outhustling his competitors: 100-hour workweeks were standard. Now that his Xiaomi has quickly emerged as one of the world’s most valuable private tech companies, and Lei ranks as the eighth-richest person in China, how has his workload shifted? It hasn’t: 100 hours remains his benchmark. Lei is unwilling to slow down if there’s even the slightest risk it will jeopardise what he’s accomplished. “If I said four years ago I would have done this,” says Lei in his Wuhan-accented Mandarin, “I would have had no credibility.”

By “this”, the 45-year-old founder and CEO of Xiaomi means conquering the world’s biggest smartphone market at lightning speed. Lei’s company didn’t even exist prior to 2010, and today its Mi phones outsell all other smartphones in China. With Asia accounting for more than half of the 1.5 billion smartphones sold worldwide each year, that feat alone has vaulted Xiaomi to number three in the world, after Samsung and Apple. Lei has been called the Steve Jobs of China, and for good reason. He has studied and replicated much of the Apple co-founder’s shtick: Showy product demos, a penchant for black T-shirts and jeans, and a startlingly close reading of Apple’s industrial design (drawing criticism of idea theft by iPhone designer Jony Ive). But Lei, who’s worth $9.9 billion, is emerging as his own business legend—at least in China. Seated at a conference table on the 15th floor of one of Xiaomi’s pair of rented offices in western Beijing’s high-tech district, he waxes poetic about the mission: “My goal is to turn Xiaomi into a national brand in China, influence all of China’s industry and benefit everyone in the world.”

Xiaomi is winning by giving the Chinese what they want: Cheap, feature-packed Android phones. Xiaomi will sell 60 million handsets in 2014, doubling 2013’s total; its $5.5 billion in sales in the first half of 2014 surpassed all of 2013, when its phone division netted an estimated $80 million.

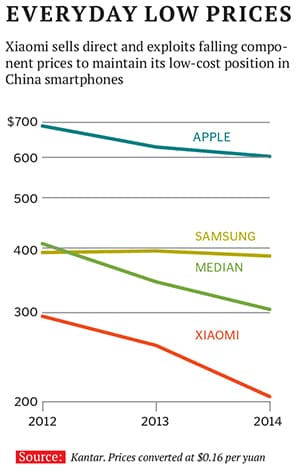

Xiaomi won China by eliminating the distance between itself and the marketplace. Everything is sold online, direct to consumers, so Xiaomi can control the experience and customer support. It buys phones in batches throughout the year, rather than placing bulk orders upfront, to exploit continually deflating component prices. Dozens of product improvements come from ideas submitted by customers on microblogging services such as Weibo. Lei has more than 4 million social followers in China and spends hours on MiTalk, the Xiaomi chat site, celebrating customer ideas and soliciting feedback. (Steve Jobs was never such a populist.) In 2012 the company started hosting an annual convention for fans and holds regular user meetups that have the feel of religious revivals, where the die-hard sing, cheer, play games and buy the company’s colourful ‘Mi Bunny’ family of plush mascots, which sell by the hundreds of thousands per month.

The fervour fuels the company’s periodic flash sales at discount prices. When Xiaomi’s first phone, the Mi1, went on sale in the fall of 2011, the company received 300,000 pre-orders in the first 34 hours. Last year it sold 100,000 of a newer model in 90 seconds. Last November 11, it sold more than 1 million phones during the Singles’ Day promotion by Alibaba.com that broke the world’s 24-hour record for total online spending.

The formula that works in China is working elsewhere. In November Xiaomi sold 10,000 phones in less than 40 seconds in Indonesia, one of six markets it has targeted for growth, along with Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan. Other regions are yet to come—including the US, though with so much to do in its core Chinese market, Lei says, that’s at least three years off.

Xiaomi, now up to 7,500 employees, has been bringing on big hires to pull off its global ambitions. Last year it lured Hugo Barra, a former vice president at Google who oversaw much of its Android products, to run all markets beyond the mainland. But Lei’s preeminence is not in question. He alone is designated as founder on the company’s website, while seven others, including company president Bin Lin, another ex-Google executive, are ‘co-founders’.

How far and high can Xiaomi go? Lei has been ratcheting his ambition northward as the successes pile up. Xiaomi is still privately held. Its last investment round in 2013, which pulled in Russian billionaire and Facebook-backer Yuri Milner, put on a value of $10 billion. Xiaomi is said to be raising more money at a $40 billion valuation, but until the deal closes Forbes pegs its value at $25 billion. Lei knows that neither number is a ceiling. “Four years ago I made a mistake” by thinking Xiaomi could be worth $10 billion, he says. At the time, “I had only worked with companies worth about $1 billion. I had never seen anything worth $100 billion.” Speaking in November at an industry conference in China, Lei set a goal of leading the world in smartphones in five to 10 years. He could get to that $100 billion with a big public stock offering à la Alibaba, but Lei says he has no plan to go public in the next five years: “The most important thing is to focus, focus, focus. If I have an IPO today, everyone will be rich, sell their shares, buy a house, buy a car and emigrate. How can you manage the company?”

Lei Jun is typical of many of China’s tech luminaries, such as Robin Li and Jack Ma, in that he toiled mostly in obscurity in his 20s and 30s before hitting the jackpot after age 40. He graduated with a computer science degree from Wuhan University and cut his teeth at Chinese anti-virus software maker Kingsoft, which he joined in 1992. Six years later he was CEO. Lei began making personal investments in Chinese startups while on the job. In his first big score, in 2004, Lei sold the online retailer Joyo.com to Amazon for $75 million. Lei left Kingsoft at the company’s IPO in 2007 and continued investing in startups, where his track record was good enough to make him a billionaire even without Xiaomi. He took early stakes in both UCWeb, a popular mobile browser sold to Alibaba, and YY.com, which offers a real-time video app and went public in New York in 2012.

Xiaomi got off the ground in 2010 after Google, complaining about censorship, shut down its China search site, Google.cn. Lei, then chairing mobile browser UCWeb, had become friends with Bin Lin, who was heading Google’s efforts to get the US company’s free Android operating software into Chinese phones. Lei saw good prospects for Android in the then Apple-dominated smartphone world. And so when Google pulled back, Lei and Lin decided to set up Xiaomi to tailor an open-source version of Android for Chinese users. The two spent months hashing out business model ideas. Lei studied Walmart’s and Costco’s histories of driving down wholesale costs to pass savings on to customers.

Lei tapped into his network among the tech elite in China and his already sizable social following to spark blockbuster flash sales of the Mi1, in September 2011, with no spending on print or TV ads. In June 2012, just prior to the release of the Mi2, Xiaomi raised $216 million in a round that valued the company at $4 billion. That was on top of earlier rounds that brought in more than $120 million from investors such as Morningside Group, Qiming Ventures, IDG and Temasek. Lei has kept the largest stake: More than 30 percent, sources say. Over the last two years, Xiaomi has continued to keep up the pressure on Samsung and Apple, pricing its phones very close to cost and generating its profit (albeit slim) on apps, services and accessories. “I have worked for John Chambers, Masayoshi Son and Larry Ellison. Lei Jun is right up there with the great CEOs of the Internet Age,” says Gary Rieschel, founding managing partner at Qiming. “Only Apple with its stores was able to go direct to consumers at scale in the technology world, and Xiaomi has even bypassed the need for stores.”

Lei’s ambitions—including reaching that enticing $100 billion valuation—require Xiaomi to succeed outside its home territory. That might be a challenge given the new crop of cheap smartphone players and potential legal challenges over the company’s technology. Its foray into India, soon to become the world’s second-biggest smartphone market, hit a roadblock immediately. Xiaomi entered India in July in a deal with Flipkart, the Amazon of the subcontinent, and has already sold more than 500,000 phones via flash sales. But in December Swedish equipment-maker Ericsson got the Delhi High Court to block Xiaomi and Flipkart from selling handsets due to claims that Xiaomi is infringing on Ericsson’s patents on 3G and Edge broadband wireless. The parties struck a deal that temporarily allowed Xiaomi to sell some devices in the country, provided that the company deposits $1.57 for every device sold.

Lei also wants to become a broadline electronics company. In November it began selling a web-connected 49-inch Mi TV, 37,000 of which sold on its release day. Google’s purchase of household-appliance supplier Nest Labs for $3.2 billion earlier this year, Lei says, sets an early standard. “Xiaomi will be an important player,” he vows, showing off a partial video recording of our conference-table talk on his Mi TV with a few taps on his mobile phone.

In November, to round out its portfolio of services and software, Xiaomi and an affiliated investment company, Shunwei, paid $300 million for a stake in video site iQiyi, a subsidiary of China’s internet search giant Baidu, opening the door to mobile entertainment. Xiaomi has a $1 billion budget for entertainment and hired Chen Tong, chief editor at one of the country’s most popular news sites, to run the business. It also took a stake in China’s video portal Youku Todou that will bring more access to content. In December Xiaomi, Shunwei and other Chinese investors plowed $40 million into US fitness tracker maker Misfit. Lei gets up from his table, finishing this rare interview. The 100-hour workweek beckons, even with a wife and two children at home. Running Xiaomi, says Lei’s friend Robin Li, the billionaire CEO of Chinese search giant Baidu, “is like competing in a triathlon: You have to be good at hardware, software and internet. He is uniquely positioned to do this, and he does it really well.”

“We’re just a young company and in a fragile position,” Lei says. But it’s one with a gaping market waiting to be pinged for a deal.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)