Our first 100 years: Steve Forbes

The year of Forbes’s founding, 1917, was one of the most momentous in history. The US entered the Great War, a dramatic break from our isolationist tradition. The October Communist coup in Russia brought into power the first modern totalitarian regime, one which would violently challenge the very existence of capitalism and the liberal democratic order.

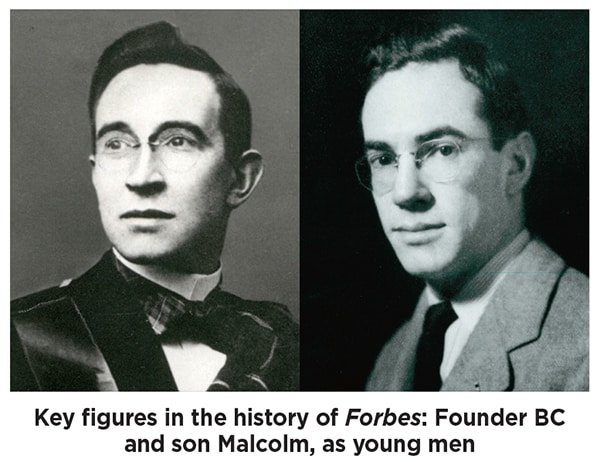

The year of Forbes’s founding, 1917, was one of the most momentous in history. The US entered the Great War, a dramatic break from our isolationist tradition. The October Communist coup in Russia brought into power the first modern totalitarian regime, one which would violently challenge the very existence of capitalism and the liberal democratic order.To launch a new publication in the midst of a world war would strike most as folly. But BC Forbes, the sixth of 10 children of a Scottish tailor, had long burned with ambition to become a business writer and, ultimately, his own boss. He first went to South Africa, where he worked for the editor of the new Rand Daily Mail, Edgar Wallace, who later achieved fame in Britain and the US as a novelist. Many a time BC wrote editorials for his oft-inebriated boss. But South Africa was too small a pond, and in 1904 BC immigrated to the US. Landing in New York, he had a hard time getting a job, but instead of going home BC decided to offer his services to an editor for free for several weeks to “prove my worth”. He had no idea whether he would be tossed out when, after the allotted time, he would ask for a salary, but like any entrepreneur, he knew that doing things the “normal” way would get him nowhere. He got the job. Full of energy, BC assumed a nom de plume and, at the same time, obtained a job with another publication, also as a business writer. Legend has it that the two editors later got into an argument over who had the better business reporter—it was BC in both cases.

BC became a renowned financial writer, not only reporting and turning out a syndicated column but also authoring books. Yet, instead of just writing about individuals who started their own firms, he itched to start one himself, and hated not using all the material he gathered. He felt the time had come to start his own publication. It was originally titled Doers and Doings, but BC was persuaded to use his surname, a not-uncommon practice in those days.

BC Forbes deeply believed in what we today call entrepreneurial capitalism. He loved chronicling the doings of business leaders—the bolder, the better. He was no apologist, however. He railed against those he felt were abusing employees or were incompetently managing their firms. He stated in the first issue of Forbes, “Business was originated to produce happiness, not to pile up millions.” He had no truck with the notion that we are ultimately governed by impersonal forces.

Forbes boomed during the 1920s. William Randolph Hearst, the media mogul who was the model for Orson Welles’s classic film Citizen Kane, offered to buy BC’s creation in 1928 for what today would be the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars. BC proudly turned him down. He soon had cause to wonder if he’d made a catastrophic mistake.

Forbes was hit hard by the Depression. By 1932, the company was bankrupt in all but name, as advertising had contracted more than 80 percent. BC kept his creation alive through his freelance earnings—he was still a columnist for the Hearst papers—and by instituting what was dubbed “Scotch week”: Every fourth week employees went without a paycheck, which meant a 25 percent pay cut. But in those desperate times people were happy just to have a job. BC himself didn’t cash any of his paychecks for several years.

Barely surviving the Depression, Forbes limped along in the 1930s, overshadowed by BusinessWeek (owned then by McGraw-Hill) and Fortune (Time Inc). In 1945, BC’s son Malcolm (MSF) joined Forbes after being discharged from the Army, where he’d been badly wounded while serving as a machine-gunner. Another son, Bruce, was already at the company.

At the time Forbes’s content was mostly made up of freelance pieces. MSF began hiring full-time editorial staffers, rightly believing that this would dramatically improve the editorial product. He also launched The Forbes Investor, a weekly newsletter that recommended stocks and analysed the previous week’s market news. The price of the newsletter was an outlandish $35 a year (Forbes subscriptions went for $4 or less), with production costs a fraction of the magazine’s. The newsletter was an instant success and provided the capital to reorganise the company.

In 1947 Forbes marked its 30th anniversary and nascent revival with a major dinner at New York’s Waldorf Astoria. New York Governor Thomas Dewey gave the evening’s major address, and he didn’t disappoint, making headlines by declaring his intention to run for President in 1948. (Although he was heavily favoured to win—Life magazine ran a photograph of Dewey with the caption “The next President travels by ferry boat over the broad waters of San Francisco Bay” before the election—Dewey lost to incumbent Harry Truman in America’s greatest electoral upset prior to Donald Trump’s stunning 2016 victory.)

Editorial content improved, as did circulation and advertising with a number of innovations. In January 1949 Forbes introduced what would become its annual report card on industries and companies, thereby starting the buildup of its statistical muscle. January traditionally was the deadest month of the year for advertising, but with this issue’s advent it became one of the best. In the 1950s the magazine began in-depth coverage of the burgeoning mutual fund industry. Every year we would give each fund a letter grade for long-term performance in up markets and another in down markets. Despite bitter memories of the Depression, millions of people were starting to invest again as their economic conditions got better.

The longtime (1961–99), brilliant, crusty, cowed-by-no-one editor James Michaels did more than anyone else to bring about Forbes’s editorial prominence. We developed a reputation for hard-hitting stories that evaluate companies the way critics critique a stage play. What made these pieces ring true was our growing sophistication in digging into corporate balance sheets in a way that no other publication did. One example: A cover story in 1998 exposing the obscure and outrageous fees charged by most annuities, which made them a poor investment for customers.

The magazine’s growing fame was accelerated in 1982 with the introduction of a special annual issue that ranked the 400 richest Americans. The idea was Malcolm’s (the “400” was inspired by the so-called 400 Ball hosted in 1892 by New York’s social queen, Caroline Astor). MSF met fierce internal resistance: How can we find out who these people are, since much of the necessary information isn’t public? How can we dig up their finances? Anyway, won’t our listing them make them targets for kidnappers, robbers and fundraisers? The editorial department conducted a “study” and told Malcolm his idea was absolutely unfeasible.

“Okay,” the boss replied. “I’ll take it out of your hands and do it myself; I’ll hire some outside staff and raid a few of yours.” Edit capitulated. In fact, the editors and reporters involved on what was dubbed “The Rich List” developed ways of getting seemingly unavailable information. The first edition was a huge success, editorially and financially, and lists became a Forbes mainstay. The key was and is credibility and innovation. For example, Forbes’s 30 Under 30, an annual list of 30 impressive young achievers in 20 different categories, has been phenomenally successful, thanks to Randall Lane, its originator and the editor of Forbes, and his editorial colleagues.

Key to Forbes’s continued success was what we now call “branding”. Having an ever better product isn’t enough, as Steve Jobs demonstrated with his emphasis on sleek and beautiful designs. In 1964, when MSF succeeded his brother Bruce, the company accelerated moves that would make Forbes synonymous globally with entrepreneurial achievement, success and the good life. MSF did things no traditional CEO would do: He collected Fabergé eggs; American presidential and historical letters, manuscripts and memorabilia; toy boats; and toy soldiers and exhibited them in a museum open to the public at the Forbes Building on lower Fifth Avenue. He acquired exotic properties in the US and around the world (see pages 48-50). Elaborate luncheons for CEOs were a routine in the brownstone house connected to the Forbes company headquarters. Each guest was given an advertising pitch before leaving. A Tiffany-made silver cup, inscribed with the person’s name and the lunch date and embossed on the bottom with a Forbes stag’s head, would be sent to each guest, along with the information that another such cup would hang in the brownstone’s wine cellar, entitling the guest to come by anytime to try the wine. None ever did.

The good feelings garnered from this kind of entertainment, however, didn’t always endure. Malcolm once invited a railroad CEO to lunch with whom he’d been exchanging barbs. It was time to bury the hatchet! The affair went well, but a few months later the magazine hit him again. The furious executive sent the cup back.

In 1967 Forbes surpassed the number of advertising pages it had run in 1929. To mark its 50th birthday, MSF threw a spectacular party at his New Jersey home. More than 500 leaders of US’s mightiest corporations and their spouses attended. The keynote address was delivered by Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a very liberal Democrat who won over the crowd with humour and the theme that government and business need not be enemies. (Malcolm had come to know Humphrey years before and had written a glowing editorial about him in 1964. Humphrey told Malcolm that the piece had helped persuade President Lyndon Johnson to choose him as his running mate.)

Forbes also celebrated its 70th anniversary at MSF’s New Jersey home. Guests still remember the 70 bagpipers marching down a hill, seemingly coming out of the mists of the nearby woods. Scores of helicopters had ferried in the corporate moguls. No surprise, the largest chopper belonged to Donald Trump.

Such events didn’t meet with universal approbation. In August 1989 MSF gave a party in Tangier, Morocco, to mark his 70th birthday at Palais Mendoub, which Forbes had purchased years before (now, fittingly, owned by the king of Morocco). Even though MSF personally footed the bills, he was excoriated in parts of the media at home—a lot of people are never short on ideas of how to spend other people’s money. To some outsiders, all of this looked like wasteful extravagance. It was the opposite: It created a global image for Forbes that is as powerful today as it was decades ago. Many businesspeople and entertainers regard landing on the cover of Forbes as the ultimate proof of their achievements. Talk about branding!

Although Forbes Inc was a fraction of the size of powerhouses such as Time, Dow Jones and McGraw-Hill, its reputation was bigger, more prestigious and more glamorous. The magazine surpassed rivals, Fortune and BusinessWeek, in the clout it exerted in the business world.

In 1992 Forbes observed its 75th anniversary with a major event at Radio City Music Hall. The highlight was addresses by former President Ronald Reagan, whose policies and adroit diplomacy had been crucial to the US winning the Cold War, and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the recently defunct Soviet Union, which had been created in 1917, the same year as Forbes magazine’s founding. What a pairing! BC would have been proud that his creation had outlasted Lenin’s.

Forbes’s post-WWII comeback and surge was in an industry whose fundamentals hadn’t seen much change since the invention of the steam-powered rotary printing press in 1843, which had made the mass-marketing of newspapers and magazines possible. But with the ascension of the internet, the print world was being decimated.

It’s a cliché to say, “You must reinvent yourself” or “Remake your company as if it were a startup”. This is very difficult for legacy companies, which is why most eventually fall by the wayside. The mind is so accustomed to—and encumbered by—seeing the world and carrying out tasks in a set way. Even when managements recognise industry-altering innovations, their responses are often too slow and unimaginative, or they go into panic mode.

In the mid-1990s most publishers thought that electronic publishing meant merely reproducing the printed page online. And just about every publisher was hesitant to make a commitment to fully developing their websites. Why give away their copy for free? Moreover, online advertising was then minuscule.

At the start of Forbes.com in 1996, we fortunately separated the online product from the magazine—different buildings, different staffs, different reporting lines. The new venture didn’t just post what had appeared in the magazine; it also created a lot of original content, a rarity for legacy publishers. Forbes.com suffered considerable losses for several years before turning profitable. But the time came when operations had to be combined. It was a cultural bloodbath, most particularly for the editorial departments. Print writers regarded their dot-com counterparts as peasants and poseurs, content to turn out plentiful but superficial and fourth-rate copy; the dot-com writers and editors saw print reporters and editors as lazy, overrated snobs.

Big changes came in 2010 at Forbes with the arrival of Lewis D’Vorkin as chief product officer. Lewis had had a varied career in print, TV and high tech. He had been at Forbes during the 1990s and most recently had run his own startup, True/Slant, in which Forbes Inc was a minority investor.

When Forbes bought out Lewis’s company, he agreed to come on board. He had a daring and original vision of what the new online world of publishing should be. He created a new contributor model that today numbers some 1,700 experts in pertinent fields. Although having spent much of his professional life in the print world, Lewis didn’t share the conceit that traditional journalism had a monopoly on discovering and purveying information for its audiences. If the content was good, who cared where it came from, including from advertisers? He boldly instituted what’s called native advertising. Under Lewis’s ceaseless prodding, his talented team constantly developed new technologies and products that continue to help readers and enhance their online experience. The challenges—and opportunities—are unending, including the new world of mobile devices, not to mention the advertising juggernauts of Google and Facebook.

But, thanks to D’Vorkin and his crew, Forbes has been in the forefront. Also helping make the company’s evolution to Forbes Media possible during this time was the arrival in 2010 of Mike Perlis as CEO.

Three years ago, Integrated Whale Media Investments, headed by TC Yam, bought a majority stake in Forbes, enabling the company to expand on the digital side and to move into other areas. Today, Forbes editorial is stronger than ever.

What’s ahead? Here’s betting that in 2117 people will be infinitely richer with an unimaginably higher standard of living than that we are experiencing today. And Forbes, if guided by the spirit of its founder, will be there to celebrate it.

Steve Forbes is Editor-in-Chief, Forbes

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X