Forbes India CEO Dialogues: India is an emerging cradle for innovation

Industry experts believe out-of-the-box ideas along with changing technology have transformed the way business is conducted. And though some challenges remain, disruption will only spur growth in the future

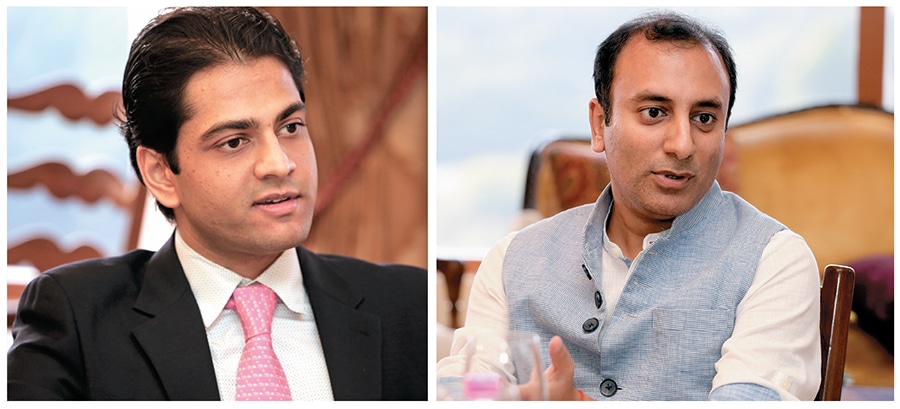

Images: Madhu Kapparath

Several new and nimble organisations are leveraging the confluence of a unique business idea and technology to solve the diverse challenges faced by the country’s over-1.2-billion population. Their emergence has given a fillip to the economy and resulted in a spurt of startups that are offering unique solutions and services. However, industry experts say that it is in no way an indication that innovation is only the premise of new-age startups. As these challengers disrupt existing business models, traditional enterprises are upgrading themselves to meet the challenges head-on.

At the Forbes India CEO Dialogues, held in partnership with Julius Bär in New Delhi on September 12, the panelists agreed that innovation is rapidly transitioning from the realm of theory to reality for Indian businesses. Moderated by Forbes India Editor Sourav Majumdar, the panel comprising Anil Rai Gupta, chairman and managing director, Havells India; Devansh Jain, director, Inox Wind; Puneet Dalmia, managing director, Dalmia Bharat; Sumant Sinha, chairman and CEO, ReNew Power; William Bissell, managing director, Fabindia; Tara Singh Vachani, CEO, Antara Senior Living; and Ashish Gumashta, CEO, Julius Baer Wealth Advisors (India) discussed the theme ‘Reboot India: Innovation and Disruption’.

“There is an environment of innovation in the country, aided by the government,” says Gupta, whose company has successfully diversified from being a wire manufacturer to a maker of consumer durables. “And not just in startups, but also in businesses like ours, which some may call brick-and-mortar.”

According to Gupta, the rise of the younger generation to leadership positions at Indian organisations, along with moves such as digitisation of the economy, is leading to out-of-the-box ideas that are being explored to reach consumers faster and service their needs faster.

Dalmia, who has attempted to bring in several process innovations at his family-owned cement company, says information and resources are no longer the sole prerogative of the senior-most executives in a company. These are now made available to young employees, which has led to the spawning and implementation of new ideas. “Creativity and human imagination is available everywhere in the organisation and we, as leaders, need to tap into the ideas of youngsters who think with lesser restraint than older people,” he says.

However, it isn’t as if innovation is not encumbered in India. The country’s energy sector is one of the best examples to illustrate this. Sinha, whose ReNew Power is India’s largest standalone independent producer of solar and wind energy, explains that though the energy sector itself has been disrupted by the availability of mass-scale and low-cost renewable power, significant government intervention, especially in power distribution, made it difficult for players in the industry to innovate. “Our governance system is still not geared to make change happen,” says Sinha. “The paradox is that we are in a highly bound sector on the one hand, while on the other, the sector itself is being disrupted as business models change dramatically [with decentralised power generation through rooftop solar and battery storage].”

Jain, whose company manufactures wind energy equipment, emphasises on the fact that disruption can have a flipside as well if policy decisions that lead to change aren’t calibrated thoughtfully.To prove his point, he mentions the sudden shift in the wind energy sector to a reverse auction-based pricing system for new projects, compared with the earlier model of pre-defined feed-in tariffs. As some of the newer wind projects were awarded at a lower tariff in some states, other state governments decided to refrain from honouring power purchase agreements signed earlier at comparatively higher tariffs. This led to a not-an-ideal situation for players like Inox Wind, which was straddled with excess inventory. Jain claims this transition led to around 8,500 jobs being lost in the wind power sector. “Government policy is something that needs to be played out in a time-bound manner, not abruptly,” he says.

Bissell, whose ethnic apparel and homeware company connects India’s rural artisans with consumers in urban areas, believes the potential threat of job losses due to innovation and disruption needs to be addressed. He cites the example of an electric car that he bought six years ago, which doesn’t have to be serviced as there is no internal combustion engine powering the automobile.

“When you switch to technology and machines, people are displaced from traditional industries. That is a challenge for the government to deal with over the next 25 years,” he explains.

Even India’s capital markets are passing through a “disruptive phase” where they are trying to figure out how to value new economy companies vis-à-vis traditional enterprises, says Gumashta of Julius Baer. “The good news is that capital to fund good ideas is abundant,” he adds.

With technology firms pervading into all spheres of daily life, the kind of competition that even a community for senior living like Antara faces has evolved, says Vachani, the scion of the health care-to-financial services Max Group, and founder chairman Analjit Singh’s daughter.

“Earlier, the kind of potential competition we faced was from those that sought to create a different kind of housing lifestyle. But now, whether it is a technology-based aggregator offering home services, security services or health care, anyone can easily curate a lot of what Antara offers in its homes,” she says. “But will those services be as affordable and of as good a quality and convenience? Not necessarily. So we still have the ability to continue to innovate in our space.”

Despite the current wave of innovation, India’s ranking in the Global Innovation Index (GII) is still low compared to peers like China, though the country has gained places over previous editions of the report put out jointly by Insead, Paris, Cornell University and World Intellectual Property Organization. In the 2017 edition of the list released this June, India ranked 60th while China was ranked 22nd. India, however, managed to gain six positions over its rank in the 2016 edition. Switzerland was the most innovative country for the seventh year in a row, while the US came in at fourth position.

Gupta of Havells India says a lot of innovation is fostered in countries like the US as against other parts of the world because in America, failure is respected. That, he adds, is unlike India, where failure is often berated and sometimes even penalised (by lenders initiating punitive action to reclaim debt extended to failed enterprises). “If innovation has to be promoted in India, failure has to be accepted and the fact that all failures aren’t linked to mala fide intentions needs to be acknowledged,” says Gupta.

Jain of Inox Wind is of the opinion that India’s education system needs to be overhauled. “A lot of innovation stems from the US simply because people have the flexibility and freedom to pursue education which is diverse and vast, and offers different perspectives to things,” he says. “Unfortunately, in India, education is mostly just rote.”

Sinha feels there is a disconnect between the industry and academia in India. “That is something that companies like ours need to address. These universities and institutes have some good resources that need to be led in the right direction,” he says.

While budding entrepreneurs have benefited from an ecosystem of domestic and international venture capitalists and private equity firms looking at India as an emerging cradle for innovation, existing organisations need to dedicate resources to foster innovation within, according to Vachani, who is also a director on the board of Max Healthcare. “After growing the [health care] business over eight years, we decided to carve out an organisation within an organisation that would solely focus on innovative ideas of the future,” she says.

Innovation obviously comes at a cost. It needs investments, which may not yield immediate returns. The good news for Indian innovators is that more capital is available to them now, than ever before. “One of the common requests I get from my clients is that they want to invest in disruptive and innovative technologies,” says Gumashta of Julius Baer. “I would say, from a capital raising perspective, we have seen a major change, where people are willing to value good ideas.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X