Sustainable solutions promise a green world

The benefits of sustainability initiatives go beyond financial outcomes. But stakeholder inputs are critical for success

(From left) Rahul Munjal, chairman and managing director, Hero Future Energies; Charles Frump, managing director, Volvo Cars India; Brian Carvalho, editor, Forbes India; Joris Dierckx, CEO & Country Head , BNP Paribas India; Alain Spohr, India MD, Alstom

(From left) Rahul Munjal, chairman and managing director, Hero Future Energies; Charles Frump, managing director, Volvo Cars India; Brian Carvalho, editor, Forbes India; Joris Dierckx, CEO & Country Head , BNP Paribas India; Alain Spohr, India MD, Alstom

Image: Madhu Kapparath

As business practices in India mature and evolve, the focus is rapidly shifting towards sustainability, conscious capitalism and positive social impact. The age-old practices of burning fossil fuel to power industry and procuring raw material at the lowest possible cost, without regard for ethical sourcing, are passé.

To delve deeper into this paradigm shift, the third edition of Forbes India Conversations—The Thought Leadership Series, in association with BNP Paribas, brought together some of the country’s top minds to discuss the importance of sustainability while devising strategies for future economic growth.

‘The Sustainability Agenda’ event held in New Delhi on February 21 began with a panel discussion titled ‘Why Sustainability is Good for Business’. It had Rahul Munjal, chairman and managing director, Hero Future Energies, Charles Frump, managing director, Volvo Cars India, Alain Spohr, India MD, Alstom, and Joris Dierckx–CEO & Country Head , BNP Paribas India, as participants. The discussion was moderated by Forbes India Editor Brian Carvalho.

Profit versus Planet

Munjal, who is regarded as one of the poster boys of India’s renewable energy sector, was emphatic about the need to align profit motives of businesses with the interests of the planet. “We know for a fact that trying to keep the temperature change to 20 Celsius today seems impossible. Are we ready for the kind of disruption that will happen to the water table of the world, are we ready for increase in sea levels; are we ready for the flora and fauna to change?” he asked.

Munjal argued that it is necessary to evaluate the price of climate change today vis-à-vis the impact it could have on future generations, especially since the cost of sustainability initiatives have fallen. “Today, sustainability or green businesses are not more expensive than business as usual,” he said.

Sharing his experience as an auto industry veteran, Frump observed that sustainability initiatives find resonance with customers as well, especially millennials, who are “willing to pay more for products that are from a sustainable business”.

BNP Paribas’s Dierckx, however, pointed out the flip side, where consumers have to pay a premium for such products. “We probably need to come to a position where they are being paid for either by consumers of products that generate these externalities [such as pollution and climate change] or the producers of them,” he said.

The payments made towards sustainable solutions need to be looked at from a different perspective, according to Spohr. The expenses could be justified if they are seen as “lifetime costs” instead of “investment, capex, or short term or acquisition costs,” he said.

High on Hydropower

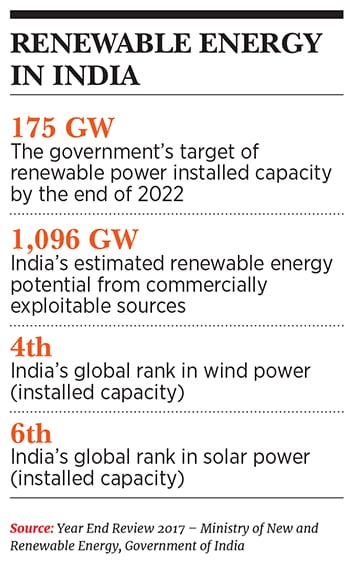

Munjal said renewable energy is a profitable business to be in as an independent power producer in both wind and solar power. “One of the reasons we got into renewable energy was because we could see the writing on the wall. The world had to go to renewables sooner or later; it was happening in the rest of the world, and we have over 300 days of sunshine in India. It just makes natural sense. India needs energy security. We also need to care about the environment. There are many wins in going for renewables rather than just one or two,” he said.

Munjal was optimistic about India achieving its target of increasing the share of renewables in the country’s energy supply to 40 percent by 2030. “Renewables had two problems: One was its price, it was expensive; the second, it was intermittent. It’s not expensive anymore. So, today, it makes economic sense to do a wind or solar project, but it is still intermittent,” he said. The solution lies in the price and technology of storage, or battery, he added. “So, very soon, it would be cheaper to have solar plus battery [generation and storage unit] and it would be cheaper than generating power from a thermal plant.”

Spohr thought hydropower complements solar and wind power, and was a bit surprised that [some] hydropower projects in India, about which the country was bullish 10 to 15 years ago, have suddenly stopped. The hydropower space could be looked at again, he felt.

The “return on effort in hydro is a lot less than in wind and solar, and that’s the reason why hydropower has been on the backfoot,” Munjal said, adding that the government should promote hydropower in a way that would yield more returns and encourage investments.

Frump asserted that the auto industry is headed towards an electrified future, and commended the government on its vision for achieving its renewable energy targets by 2030, by pushing for electric cars. A smart city would need to have the necessary charging infrastructure, which would be a crucial enabler for electrification, he added.

Munjal raised an important caveat, which found resonance with the other panelists as well. “If we move to electric today, we are just shifting the burden from burning gas to burning coal because electricity comes from coal. So you cannot shift the burden; you need to have renewables in there to make electric actually a better environmental solution,” he said. The government is making a lot of noise but there is no policy yet, he regretted. “Hopefully there will be a policy soon, but the whole point is before we go electric we should be electric on renewables, not on coal because that defeats the purpose,” he added.

However, such infrastructure development would need green investments and alignment of financial markets with sustainable development. As a start, Dierckx suggested that a clear definition and standards of “green” need to be set. “There is a working decision for green bonds, but what exactly is a green loan, what exactly is green supply chain financing still needs to be defined,” he said.

After that, government incentives and public policy inevitably play an important role, Dierckx added. For instance, he suggested extending the priority sector lending obligation for banks to stimulate financing of sustainable business models. A third factor that could drive investments would be market flexibility, he said. “The market is still the best place to allocate capital in the most efficient manner; so leaving the freedom of capital allocation to the market. And to a certain extent, what would possibly be helpful is to open up that market specifically for international investors.”

Ideas for the Future

Reiterating that “sustainability means sometimes spending more money at the beginning in order to save in the long run”, Spohr said the L1 concept of procurement (awarding tenders to the lowest bidder) hinders innovation and high quality. But he remained optimistic, “because people are becoming more and more aware that quality, innovation and creativity can make a difference in the long run.”

Frump said that since the issue is about emissions and climate change, instead of just focusing on innovative solutions and end results, the government needs to put out a firm roadmap or method to promote sustainable mobility.

He cited the example of London to highlight the need to align policy and incentives with sustainability objectives. “Ten years ago, London was far more polluted than Delhi from a PM2.5 [atmospheric particulate matter concentrations] perspective and it has aligned its taxation to automobile emissions. And now you look at the PM2.5—it is under 50 in London, and over 500 here in Delhi,” he said. “One thing is to define policies, and the second is to drive them for implementation,” Spohr added. Since most trains run on electricity, successful generation of green electricity would benefit the passenger transport industry as well, he said; his company, Alstom, specialises in transportation solutions for railways.

Dierckx concluded the discussion by raising a few questions, such as what is the price that consumers are willing to pay for sustainability, and how would the government allocate its true costs towards it. In terms of public transport, he wondered how the cost of pollution could be allocated, and the possibility of cross subsidisation from more polluting cars to cleaner public transport systems. “So, it is very much dependent on where the market is in its development,” he said.

Since the cost of generating wind and solar power are competitive, “coming to a business model becomes easier because it is immediately profitable,” he added. Dierckx expressed the need to go into business models that focus more on positive impacts socially and environmentally, but with a trade-off in economic return.

Lastly, he raised the issue of finding the right type of investors, and the need for markets to evolve. “The easy example is impact investing; social impact bonds for example. Right now, there is only a market for those bonds in the US and the UK. It is beginning to develop in Western Europe, but even there it’s still a bit of a stretch, and the actual investor appetite is relatively low compared to the total size of the market,” he said.

“So, it’s really defining where the investment is—on the spectrum of immediately profitable [on one end] and much more focussed and driven by sustainability [on the other]—and linking that to the right type of investor”, Dierckx said.

The panelists agreed on the need for a clear commitment from all stakeholders to develop policies, strategies, incentives and infrastructure for implementation of sustainable solutions.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)