How the camel milk trend may save the camels

As the camel population falls drastically in India, increasing the demand for its milk products can help revive their numbers and the livelihoods of their herders

There was a time, not so long ago, when the only mode of transport across the deserts of western India was the camel. Able to effortlessly traverse the hostile terrain and weather, hundreds of thousands of these animals, for centuries, hauled people and goods across Gujarat and Rajasthan, while ploughing farmlands, and lugging farm produce and equipment in the neighbouring states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

Then came the highways—just between 2014 and 2018, Rajasthan built 4,116 km of highways at an expenditure of `13,614 crore—bringing in their wake buses, trucks and tractors. The camel, considered to be as integral to western India’s landscape as the sand dunes, rapidly found itself irrelevant and unwanted, and herders began to feel the burden of sustaining large numbers of animals.

“When the camel no longer served the purpose of transportation, the herders began to abandon their animals because they were not able to make any income to sustain them,” says Ilse Kohler-Rollefson, founder of Camel Charisma, which is based in Sadri, Rajasthan, and has been working with herders to promote alternative means of livelihoods through camel-based products. “In order to make money, some herders clandestinely sold camels for meat. No one talked about it, because it went against their social norms. But not having any other source of income meant they had to close their eyes to tradition.”

With the intention of stopping this illegal slaughter, the Rajasthan government declared the camel as the state animal in 2014, and stopped its sale to other states. “Traditionally, the Raikas—who have been camel herders for centuries—would not sell their animals for slaughter. Male camels were sold at the Pushkar cattle fair as draught animals for neighbouring states, and they would fetch good prices. But the effect of the government decision was a dramatic drop in prices: From `10,000 to `15,000 for a male camel, prices fell to `1,000. This has been a disaster for the Raikas,” says Sundeep Bali, a photographer and artist who has been documenting the life of the Raikas for several years, and who works closely with People For Animals (PFA), in Sirohi, Rajasthan. “As highways began to crisscross the state, they began to disrupt the traditional migration routes of the Raikas; you cannot cross multiple highways with 3,000 animals.”

The combined effect of these developments has meant the population of camels in India has seen a dramatic decline, compared to a time when Rajasthan alone was home to 7.56 lakh camels in 1983. According to the 20th Livestock Census, the camel population in the state fell by a staggering 34.69 percent between 2012 and 2019. In 2012, there were 3.26 lakh camels in Rajasthan, which declined to 2.13 lakh in 2019. In Gujarat, the population fell from 30,000 to 28,000, in Haryana from 19,000 to 5,000 and in Uttar Pradesh from 8,000 to just 2,000.

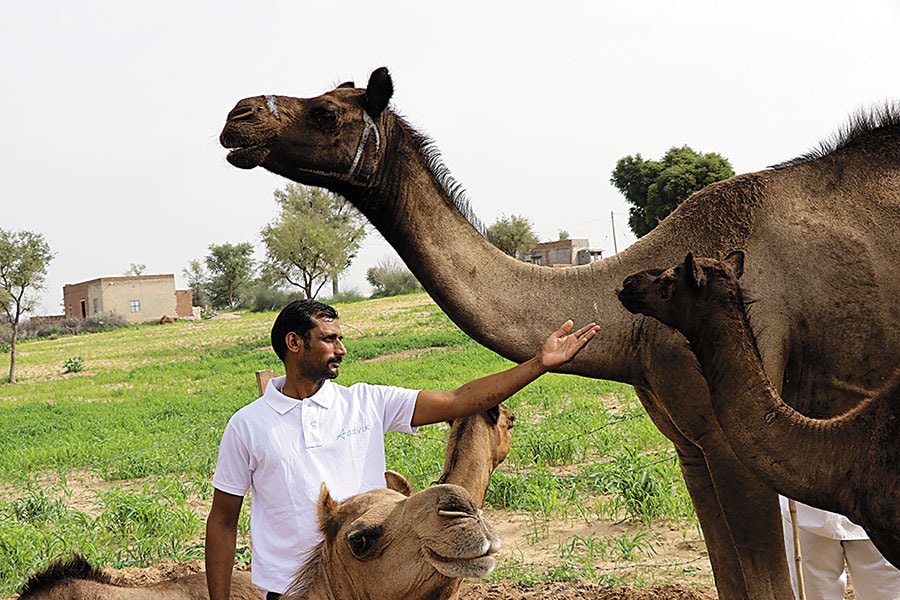

After highways were built, camels were no longer used as means of transport and herders struggled to sustain them

After highways were built, camels were no longer used as means of transport and herders struggled to sustain them

.jpg) Camel Charisma sells frozen camel milk and camel cheese, which they position as a heritage health food

Camel Charisma sells frozen camel milk and camel cheese, which they position as a heritage health food

Divyesh Ajmera, founder of DNS Global Foods, sells freeze-dried camel milk in the powder form

Divyesh Ajmera, founder of DNS Global Foods, sells freeze-dried camel milk in the powder form